My work, using camera traps in wildlife monitoring projects, involves two extremes. I’m either hiking up a never-ending hill, splashing through a stream, and doing that very careful way of digging my heels into the hillside and kind of leaning backward so I don’t slide down a mountain, or I’m doing a whole lot of sitting. The sitting comes in two forms, the first is sitting in my truck, driving across the country to a project site, and the second is sitting in front of my computer reviewing thousands of wildlife videos and entering information from those videos into a database.

Whenever I’m sitting in my truck, driving on some probably bumpy road, I’m listening to podcasts. I enjoy a variety of podcasts about a wide range of topics from the silly to the serious. Lately, my serious-leaning podcasts have been telling me over and over that artificial intelligence, AI, is an unstoppable force that’s charging at us, ready to change everything. Nobody can seem to quite articulate if it’s going to be great or horrendous, but they do seem to agree that’s going to happen either way. Since I’m me and I tend to worry about me-stuff, I’ve been wondering how AI is going to affect my work.

The fact is, I’m going to find out very shortly. Over the last year I’ve been working with an educational organization that brings high school students to Costa Rica to study tropical biology. The students go to a beautiful property where they hike in the jungle, study leafcutter ants, and, thanks to a partnership with yours truly, study the results of a camera trap project in forests around the community. We’ve also begun to deploy bioacoustics monitoring systems. These little devices work like camera traps, except with sound. They detect the presence of wildlife not with a video but with a recording of the sounds that they make.

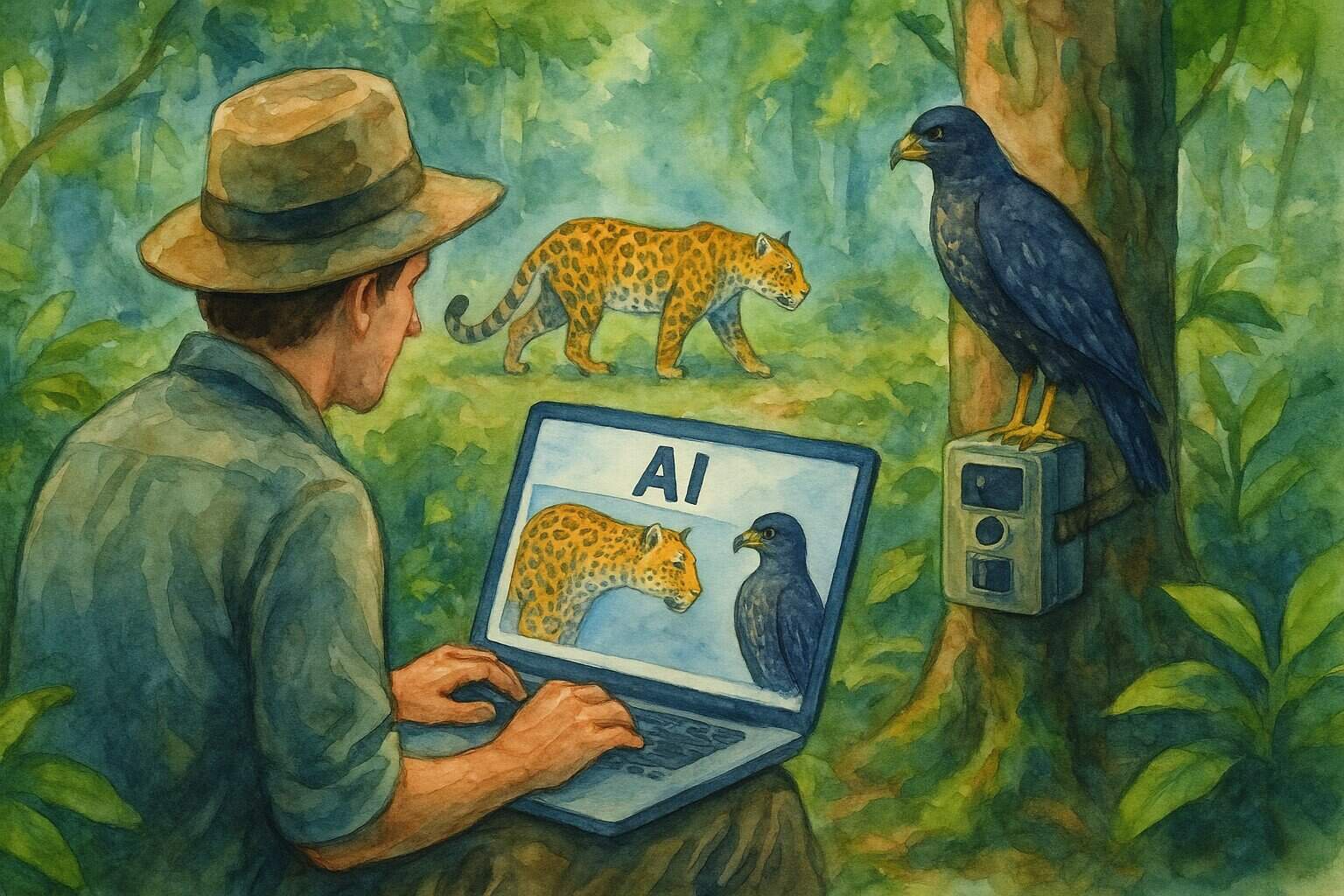

Artificial intelligence comes into the picture in two ways. First, the plan is for students to use AI to create a database of the jaguars that we’ve been recording with the camera traps. Each jaguar has a unique pattern of spots, or rosettes, and they’re going to create a program that identifies the jaguars automatically. The second use of AI has to do with the acoustic monitors. These little devices record a mishmash of all the sounds in their location in the forest, and the students will use AI to search for individual species in the mixture of forest noises. The plan is for the students to begin to use AI to analyze the project’s data at the beginning of next year.

While that will be my first taste of using AI in wildlife monitoring, I’m sure there’s more to come in the not-so-distant future. I can imagine plugging an SD card into my computer and telling a program to extract all of the information from each video and enter it into a database, a task that currently takes many hours of reviewing videos and manually entering the information.

I’ll be gaining a huge increase in efficiency, but it won’t come without a loss. I’ll lose everything I learn while reviewing video after video. After seeing thousands of twenty second clips, I have a good feel for the gate of a walking puma, I know what white-tailed deer do when they hear a sound that makes them nervous, sometimes I even learn things without knowing I’m learning them. Here’s an example.

I’ve seen hundreds, if not thousands, of videos of common black hawks, a black bird of prey with a few white streaks, yellow legs, and a yellow beak with a black tip. About six months ago, I clicked on a video that featured what looked like a common black hawk, but something was just a little off.

It was black with white streaks, had yellow legs, and a yellow beak with a black tip but something in my brain said it was slightly different than all of the other black hawk videos. I followed my hunch and realized I was looking at a zone-tailed hawk, a bird I’d never recorded before. Then just last month, the same thing happened, a bird that very much resembled a common black hawk but was just a little too tall. It turned out to be a great black hawk.

If I hadn’t spent that time manually reviewing all of those hawk videos, I’m confident that I never would have noticed the difference between these three species of raptor. Will AI be able to tell the difference between them? Even if it can, without having put in the time myself, I wouldn’t have the expertise to check its work. I’d have to take its word for it. The whole point of getting into this line of work was to learn as much about Costa Rica’s wildlife as possible, I hope in the end AI helps, rather than hinders, me reaching that goal.

Take a look for yourself. Can you see the difference between these three very similar species? Do you think AI will be able to?

About the Author

Vincent Losasso, founder of Guanacaste Wildlife Monitoring, is a biologist who works with camera traps throughout Costa Rica.