#IamCharlieHebdo#IAmNotCharlieHebdo#IAmAhmed#IAmFreedomOfExpression#IAmFreedomOfExpressionButNotHateSpeech#TheProblemIsBlasphemy#TheProblemIsIntolerance#TheProblemIsIslam#TheProblemIsExtremeIslam…

Yes, political opinions took over social networks early this year. It was a gloomy start to 2015, a year we began already laden down with heavy baggage: In the preceding months, we not only failed to #GetBackOurGirls, but we also #LostAnEntireVillageInNigeria. We then witnessed a blogger receiving 50 lashes out of 1,000 following a conviction for insulting Islam in Saudi Arabia, and just three days before Christmas, we got the news that Taliban gunmen killed 144 people, mainly kids, in a school in Pakistan. And then, there was Paris. The events in France and around the world this month, but also the violence that extremist religious and non-religious groups have been using to assert their beliefs for decades, is a human tragedy because of the lives of men, women and kids that were taken. It is also a human tragedy because it shows how far we remain from the political ideals we have been trying, for centuries, to realize and secure.

It’s hard to be optimistic about the future. The immense mobilization of citizens and political leaders in Paris and in other cities may be taken as a sign of hope, although it has yet to make a substantial contribution to the debate. A one-day march does not involve enough effort to result in deep reflection on the causes of this phenomenon, not to mention its solutions. Moreover, the news of hate-filled backlashes against mosques in Paris, bigoted analyses in conservative media, and anti-Muslim protests in Germany, make us think twice about the progress we thought we had made in defending and exercising freedom of speech. Many people fail to understand that freedom is not a zero-sum game: The repression of Islam doesn’t mean more freedom for everyone else. Homogeneity is not synonymous with freedom.

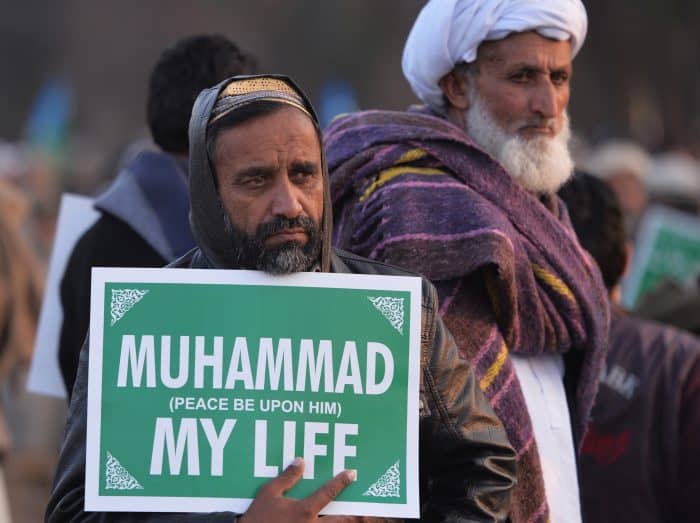

There is hope in the many people who condemn extreme Islam but avoid generalizations. Fortunately, after this episode, many respected Muslim and non-Muslim voices insisted that the Koran and the mandates of Islam do not command the followers of the Prophet Muhammad to punish blasphemers. They pointed out that the word “blasphemy” is not even in the Koran, nor is the idea that depictions of the prophet should be revenged. Instead of repeating empty phrases without historical foundation, we can only usefully contribute to the debate by inquiring seriously and learning about other people’s beliefs – whether Christian, Hindu, Jewish, Buddhist, atheist or agnostic.

However, one of the saddest outcomes of the attacks in Paris was a realization of the extent of prejudice and ignorance across society in these matters. This was evident on social networks and even news programs. “Terror expert” Steven Emerson claimed on Fox News that the city of Birmingham, England, has become a “totally Muslim” city where non-Muslims never go. He also added that the there are parts of London where Muslim religious police enforce the Koran’s doctrine, inflicting serious injury on people who don’t comply – for example, people who do not wear Muslim attire. Host Jeanine Pirro seconded Emerson, saying that “it sounded like a caliphate within a particular country.” When asked about Emerson’s comments, British Prime Minister David Cameron’s reply was: “He’s a complete idiot.” Indeed, he is, and so is Pirro. So what to do with #Idiots? The answer is #Education.

But the issue is more complex than one of education – politics are involved, too. In his very eloquent column in the aftermath of the attacks, Fareed Zakaria reminds us that the idea that Islam requires that its followers use violence to avenge any insult against the Prophet Muhammad is a creation of politicians and clerics to gain political support. He rightly points toward the problem of linking political power to religious fanaticism: “When governments try to curry favor with fanatics, eventually the fanatics take the law into their own hands.” If states keep supporting by action or inaction the sources of religious fanaticism in order to achieve their political, economic or ideological goals, the threat of extremist attacks will persist. We should not forget that one of the main victories for freedom in Western countries, not only for freedom of religion, was the separation of church and state. The politics of religion is one of today’s biggest challenges for modern diplomacy, partly because of the complex relationship between religion’s public and private expressions.

Religion, it has been said, is exclusively a private matter. But it’s not. I don’t mean that the state should be able to intrude on the sphere of our personal and private beliefs. But when we are outspoken about our faith or when we practice our religious rituals in public, we are engaging with other citizens, and must consider others. As with freedom of expression, the rule of thumb is that as long as we’re not hurting others, we’re free to exercise our freedoms. The philosophical and legal debates about what “hurt” means or the limits of our freedoms are endless. But for now, let’s just state that, as obvious as it sounds, when people kill to defend their beliefs they are not exercising their freedom, but imposing their creed. And here is where the values of democracy need to be remembered: In a democracy no single person – not the president, not a cleric, not a priest, not a general – imposes their will. Continuous negotiation and debate of interests and beliefs is harder than shooting a gun, but is the only path to freedom.

In her book “Memoirs of Hadrian,” French writer Marguerite Yourcenar remembers Flaubert’s words summarizing the period of Emperor Hadrian’s rule: “Just when the gods had ceased to be, and the Christ had not yet come, there was a unique moment in history, between Cicero and Marcus Aurelius, when man stood alone.” Religions, holy wars, crusades, goddesses, gods, saints and prophets have come and gone through the centuries; temples have crumbled and churches have been sold; and yet the human being is the only one who persists. Today it is us, tomorrow it will be our children, and in a thousand years there will be whole new generations who will probably have their own gods and beliefs – extreme and not extreme. To get there, however, to survive our own ghosts, we need to use the tools of politics and the ideals of democracy to establish the terms and conditions for a more civilized and egalitarian way of living. If we learned to use our massive capital of political opinion and religious beliefs to this end, we would be better off. #IMayOrMayNotBeCharlieButIWantTheFreedomToDiscussIt.

Tomás Quesada-Alpízar is pursuing his doctoral degree in politics at the University of Oxford. In “Politic(o)s,” published at the start of every month, he explores current events and political issues in Costa Rica and around the world. He welcomes reader questions and comments at politicostt@gmail.com.