Three Latin American countries hold elections next month — Brazil, Uruguay and Bolivia — a crunch test for ruling leftists seeking to bolster budding dynasties in the face of a regional slowdown.

All three countries have become symbols of the region’s leftward tilt in recent years, but only Bolivia looks sure to continue the trend.

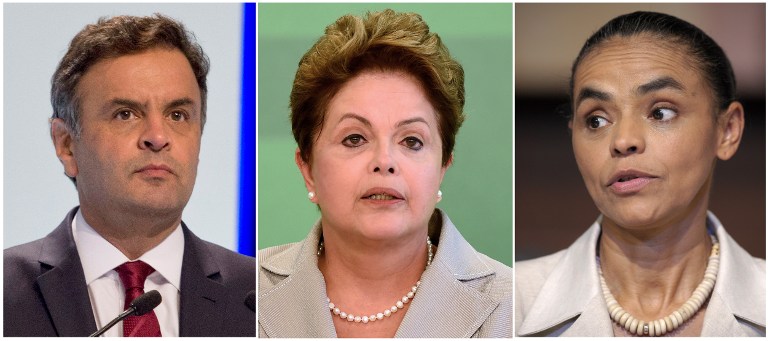

In Brazil, Dilma Rousseff, an economist and former guerrilla with a no-nonsense reputation, is trying to extend the Workers’ Party’s nearly 12-year reign by winning a second term like her charismatic predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

In Uruguay, fellow ex-guerrilla José Mujica, a folksy iconoclast known for legalizing marijuana and living in a run-down house, is looking to hand power back to his Broad Front party predecessor, medical doctor Tabaré Vázquez, the country’s president from 2005 to 2010.

And in Bolivia, Evo Morales, a virulent critic of the United States who became the country’s first indigenous president in 2006, is seeking a third term after winning a Supreme Court ruling allowing him to stand again under a new constitution.

“If you had asked me about these elections a year ago, I’d have told you that in all three cases the ruling parties were sure to win,” said Carlos Malamud, a Latin America specialist at the Real Instituto Elcano in Madrid.

“But these past few months, in both Uruguay and Brazil, the scenario has evolved considerably.”

In Brazil, the largest economy in Latin America and seventh-largest in the world, the October 5 vote has been shaken by the shocking plane crash that killed Socialist candidate Eduardo Campos last month.

His running mate, 56-year-old environmentalist Marina Silva, took his place and immediately emerged as a far greater threat to Rousseff, 66.

The latest opinion poll indicates Silva would win an October 26 runoff against the incumbent by a margin of 47 percent to 43 percent.

Silva, an Evangelical Christian who appeals to both religious conservatives and the left, has vowed to be Brazil’s first “poor, black” president, scooping up undecided voters with the promise of a new direction for a recession-hit country swept by massive protests last year.

“She has come to embody the face of change,” said André César of consultancy Prospectiva.

In Uruguay, the race for the October 26 vote has also been rattled by an unexpected latecomer.

Luis Lacalle Pou, the son of a former president, defied forecasts to win the center-right National Party’s primary in June, and has since shot up in the polls.

The latest gives him 28 percent of the vote, to 40 percent for Vazquez.

The little-known 41-year-old has brought new energy to a race long seen as a cinch for 74-year-old Vázquez, who doesn’t use social networks, refuses debates and “thinks the electorate is still the same as 10 years ago,” said Ricardo López Göttig of regional think-tank Cadal.

Both the Brazilian and Uruguayan newcomers have been boosted by “a climate of disappointment, fatigue, a general bad mood after a series of leftist governments,” said Adolfo Garcé, a social scientist at Montevideo University.

Morales, the exception

Bolivia’s October 12 vote looks less volatile, with Morales polling at 56 percent — far ahead of center-right rival Samuel Doria Medina’s 17 percent.

Morales, 54, has also refused to debate his opponent.

But with economic growth projected at five percent this year, he doesn’t need to.

“Morales has never debated in his previous elections and that has always brought him success. Why would he do it now?” said Marcelo Silva, a professor at La Paz University.

But elsewhere in the region, the end of a so-called “golden decade” of strong economic growth has brought an increasingly restless electorate, said Daniel Zovatto, Latin America director at the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

After expanding by 5.9 percent in 2010 and 4.3 percent in 2011, the region’s economies are expected to grow just 2.7 percent this year, according to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

“Part of the new middle class could slip back into poverty. Or demand a better quality of life, more public services,” said Zovatto.

“The winds of change are starting to blow in the region.”