This Sunday, Hondurans will mark the 6th anniversary of a military coup that catapulted the Central American nation into becoming the region’s murder capital – with targeted killings of journalists, political activists and labor leaders rising to unprecedented levels. One of the alleged orchestrators of that coup, Miguel Facussé Barjum, died late this past Monday night of causes not yet disclosed, just two months shy of his 91st birthday. His death was first announced on the website of the consumer products manufacturing company he founded in July 1960, Dinant Chemicals of Central America, S.A. At the time of his death, Facussé still served as its executive president and is reputed to have been one of the richest men in the country – and perhaps its most ruthless. His sudden death may mean that many of the murders and other crimes of which he has been accused will remain unpunished.

Although a death at that age is not unusual, it is odd that no cause of death has been reported in any of the press. But then, Miguel Facussé did not live a “usual” life. He was born in Tegucigalpa on Aug. 14, 1924, the seventh of nine children. His parents were Christian Palestinian immigrants to Honduras. He went to Notre Dame University in the United States, where, according to the biography on his company website, he received a Bachelor of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering. He later moved to Costa Rica where he served for a time as general manager of Taca Airlines. Shortly thereafter, he moved back to Tegucigalpa and launched Dinant Corporation.

Facussé rapidly rose to political prominence in Honduras. His business tenacity, commended by some, meant that Facussé would stop at nothing in dealing with his opponents. His legacy is one of both business acumen and violence.

A statement from his company called him “a pioneer with unflinching spirit”; that spirit often led to less than peaceful means, and he has been termed by many as “cold-blooded” and “ruthless.”

In 2012, Facussé was accused of “crimes against humanity” in the International Criminal Court for his role in a bloody land conflict raging in northeastern Honduras between his company, Dinant, and the peasant farmers of the area. Dozens – and likely hundreds – of peasants and solidarity workers have been killed in that conflict. Most prominently, Facussé was accused of orchestrating the 2012 murder of human rights lawyer Antonio Trejo, who was working with displaced families and against Facussé in the lower Aguán River valley, also known as Bajo Aguán.

In an interview with The Los Angeles Times he talked about the accusations that he was behind the killing of Trejo. Facussé reportedly told the Times reporter, “I probably had reasons to kill him.” However, he denied it, continuing, “but I’m not a killer.”

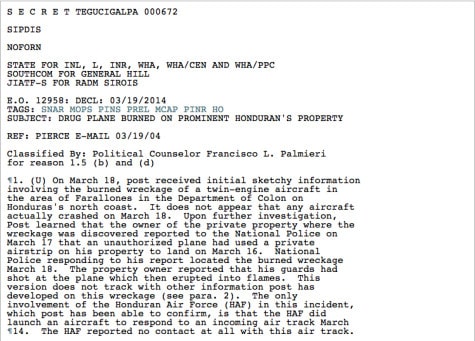

Facussé has been implicated in many other extra-legal activities as well. Wikileaks cables released in 2011 show that the U.S. Embassy in Honduras, as early as 2004, believed Facussé was also involved in drug trafficking. The media group Reporters Without Borders has also called him a “predator” for his role in a crackdown on opposition and grassroots media in Honduras.

Community Radio station KGNU in Boulder, Colorado, was one of the first news outlets in the United States to report Facussé’s death. Their reporter had been fired on by a security guard at one of the palm oil plantations while traveling with a human rights delegation to the region. These plantations are where the majority of the violence of which Facussé is accused has occurred. Much of the population of northeastern Honduras are Garifuna and face cultural and racial discrimination, as well.

At the time of the June 2009 military coup that deposed elected President Manuel Zelaya, Miguel Facussé – whose nephew Carlos Roberto Flores Facussé was a Honduran president from 1998-2002 – was very supportive. His private plane was even used to illegally transport Zelaya’s foreign minister out of the country against her will. Facussé, along with other business leaders opposed to Zelaya’s reforms, called him a “puppet” of Venezuela’s former President Hugo Chávez, and said that Zelaya was “bad for business” in Honduras.

Facussé’s Dinant Corporation has been the largest producer of palm oil in Honduras since it began production in 2006. The oil — used in everyday foodstuffs as well as in beauty products — is made from the processed fruit of African palm trees. In order to successfully produce substantial amounts of oil, Facussé needed land for planting.

Beginning in 1992 as part of a nationwide privatization campaign, Facussé, along with a few other Honduran businessmen, began to acquire land in the lower Aguán region in the northeastern part of Honduras. He came to control over 22,000 acres of palm oil plantations. The land was previously in the hands of peasant farmer cooperatives that claim these “purchases” were made through intimidation, bribery and coercion. For this reason, many peasant farmers in the area still believe the land is rightfully theirs and they are struggling to regain control of it.

Since the 1990s, peasant farmers of the area have held rallies, marches and even occupied the land, seizing control of parts of the plantations – sometimes for weeks at a time. However, usually, these peasants are violently removed and their movements repressed by police friendly to Facussé or by Facussé’s own private security guards. Houses in small communities of displaced farmers have been bulldozed and burned.

Ninety-two people were killed in these land disputes between 2009 and 2012, according to a 2014 report by Human Rights Watch. That number is likely much higher. Many more have been subject to non-lethal violence and torture. Almost exclusively, the peasants targeted have been part of organized peasant resistance movements in the area.

According to a 2013 report in Dollars & Sense Magazine, Facussé’s security guards are believed to have been directly involved in many of these deaths. The body of Gregorio Chávez, a peasant from the community of La Panamá, was found in an unmarked grave deep inside one of Facussé’s palm plantations. The body showed signs of torture before death.

These crimes against local farmers have been carried out with impunity and to such a level that past-President Porfirio Lobo called the situation a “national security crisis.” According to the 2014 Human Rights Watch report, of the 73 killings linked to land conflicts that the Honduran government recorded, only seven had been brought to trial.

As a result of his involvement in this violent conflict, Facussé lost several international development loans over the years. In 2014, the World Bank Group’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) noted the violence in Aguán as well as Facussé’s probable involvement, and implemented an action plan to remedy the situation before more loans are made. U.S. Rep. Howard Berman mentioned Facussé in a letter to then-Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, saying U.S. aid should be withheld until he is investigated for potential human rights violations.

Although Facussé was the figurehead of violence and impunity in Bajo Aguán, what impact his death will have on the region remains unclear. Gilberto Ríos, former country director of FIAN International, who worked closely with peasant farmers in Aguán until two months ago, told The Tico Times emphatically that nothing will change as a result of Facussé’s death.

“In [Facussé’s] lands, the campesinos enter and are then dislocated by the police and Facussé’s private guards, who are permanently in the area. But that will continue with Facussé or without Facussé,” Ríos said. “His matters will be handled by his executives and surely by his children.”

Although a successor has not yet been named, Facussé is survived by several children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews.

A new feature-length film, “Resistencia: The Fight for the Aguán Valley,” will be launched on June 28th and available for free online viewing for two weeks.

Resistencia: The Fight for the Aguan Valley | OFFICIAL TRAILER from Makila, Coop on Vimeo.

–

Sarah Blaskey is a freelance journalist based in Costa Rica. Her 2013 article “Palm Oil Oppression” appeared in the magazine Dollars & Sense. Norman Stockwell is based in Madison, Wisconsin, and frequently contributes to The Tico Times. His reporting on the Honduran presidential election of 2013 can be found in The Progressive magazine and the Capital Times.