Long before hordes of tourists and biologists began flocking to Costa Rica for its amazing biodiversity, the country’s native peoples were the area’s first wildlife experts. Through close observation during frequent close encounters with animals, Costa Rica’s indigenous populations built up extensive mythologies surrounding the country’s wildlife. These beliefs are best preserved among Costa Rica’s Bribrí and Boruca; animals feature prominently in their legends, healing ceremonies and even their dreams.

Creature clairvoyance

Shamans use the appearance of certain animals in dreams to predict the possible fate of the dreamer. A vulture (Cathartidae) in a dream signals that the dreamer is sick with a parasite, while a child who dreams of parrots (Psittacidae) will likely grow up to become a healer. A pregnant woman who dreams of a motmot (Momotidae) is likely to have a miscarriage.

Another traditional belief is that the traits of certain revered animals can be bestowed on children while they are still in the womb. Placing the right foot of a water opossum (Chironectes minimus) in the hut of a pregnant woman can ensure that the child will be born with greater fishing skills; doing the same with the claws of a northern tamandua (Tamandua mexicana) can endow a new baby with resilience.

Animals also play a significant role in beliefs about death. Both the common opossum (Didelphis marsupials) and the naked-tailed armadillo (Cabassous centralis) are seen by the the Bribrí people as harbingers of death. This belief is still embodied in the modern Spanish name of the naked-tailed armadillo, madillo zopilote, which means vulture armadillo. Another animal, the silky anteater (Cyclopes didactylus), is believed to carry the Bribrí’s souls to heaven.

Creation

Usually depicted as scary and violent, a vampire bat (Phyllostomidae) is the unlikely hero of the Bribrí’s creation myth.

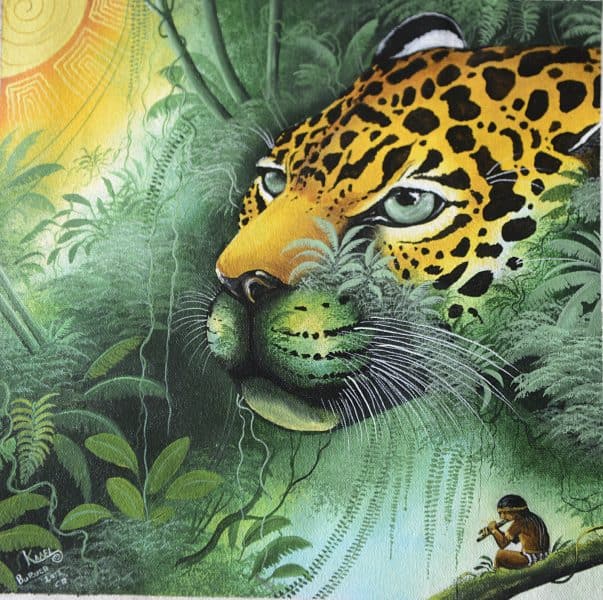

The story begins on an earth without soil or plants. Only rock and gravel covered the planet’s surface until a vampire bat flew into the center of the earth to feed off the blood of a baby jaguar (Panthera onca). With that nourishment, the bat was able to return to the earth’s surface and fertilize it. Using the guano left behind by the bat, the Bribrí god Sibú was able to plant the world’s first tree.

Spirit animals

Though many of the Boruca traditions have been lost over time, every year since the Spanish conquest, the Boruca have put on the Juego de los Diablitos (Little Devils’ Game), where the performers often dress in animal masks. Usually depicting strong animals, like the jaguar, or wise animals, like an owl or parrot, the masks represent the inner traits of the wearer.

Both Boruca and Bribrí legends also include the belief that certain animals on earth carry the spirit of gods.

In Boruca legends, quetzals (Pharomachrus mocinno) carry the spirit of the great warrior Satú. According to the legend, Satú was born to a great chief; on the day of his birth, a quetzal came down to the village to sing. As a tribute, the villagers made Satú a medallion shaped like a quetzal that would protect him. Satú was never hurt in battle while he wore the medallion; in battle, quetzals protect the Bocura.

But one day in a fit of jealousy, Satú’s uncle stole the medallion while he slept. The next day, while Satú was unprotected, his uncle killed him in the forest, but a quetzal flew down and sat over Satú’s body, it then flew away to live in the mountains where it stayed forever, carrying Satú’s spirit.

The Bribrí people believe that all the world’s tapirs (Tapirus bairdii) are spirits of a tapir god, the sister of Sibú. Legend has it that Sibú planned to marry off his sister in exchange for a wife of his own, but because she can tell the future, Tapir could see her brother’s intentions and could also see that if she married, it would end unhappily. Tapir refused to get married, so her brother sent some of her spirit to earth for the Bribrí to hunt.

Because of their beliefs, Bribrís have extensive ceremonies surrounding tapir hunting. Only certain sects of Bribrís can hunt tapirs, and only one woman per village is trained to cook the animal properly. Any violations of the ritual will incur the wrath of the Tapir god.

Read more “Into the Wild” columns here

This piece was originally published on Feb. 8, 2015.