As the infrastructure of Costa Rica advances, with new four-lane highways and a series of bypasses around San José that avoid the narrow, congested streets of the city, one relic hangs on—the one-lane bridge.

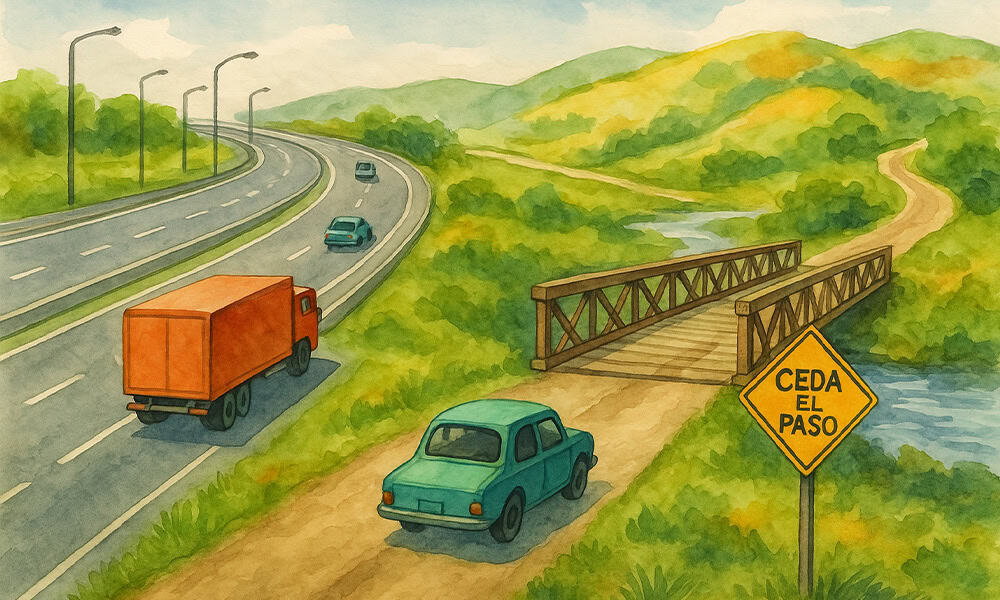

There are about 6,500 bridges in Costa Rica, and it sometimes seems as if at least half fit only one car at a time, especially in rural or less populated areas. They pop up anywhere there is a stream, river, or chasm to be crossed. Many are approached down a long hill or around a sharp curve. The Ceda el paso (yield) sign is on one side only, though it is always a good idea to enter the bridge slowly even on the side with the right of way.

A road I drive regularly is the well-traveled 35-kilometer highway between San Isidro de El General and Playa Dominical. It is a winding mountain road that presents numerous challenges to drivers unfamiliar with its narrow curves and steep drops—it descends 1,200 meters (almost 4,000 feet) in elevation in about 16 km (10 miles). Adding to the stress are a pair of one-lane bridges that have long caused backups on busy days. But at long last, change is coming.

The most troublesome was a single-lane Bailey Bridge located at the base of a long, steep hill that crossed the Río Pacuar. The Bailey bridge is a portable, pre-fabricated truss bridge originally used during World War II. While often used as a temporary solution, this one has stood for decades. Visibility was limited coming from either direction.

On weekends when thousands flocked to the beaches, a wait of several minutes during peak hours was guaranteed. But now it is closed, and work is ongoing to have a full, double-lane bridge in place by month’s end. The other one-lane bridge closer to the beach is also scheduled to be widened as soon as this bridge is complete.

One may ask why there are so many one-lane bridges to begin with. Along the Pacific Coast, many of the old one-lane roads date back to the time when the area was served by railroads. When the tracks were removed and the roads paved for vehicles, the narrow bridges remained. As for the many others, my Tico family likes to say that the other lane of the bridge ended up in the pockets of government officials in charge.

I have another, more sentimental explanation. They are remnants of the old Costa Rica, back when this was a predominantly rural, agricultural country. In 1980, the population was 2.2 million and there were about 180,000 vehicles on the roads—one vehicle for every 12 people.

Today the country has about 5.4 million people and 1.6 million vehicles, almost one for every three people. Suddenly the one-lane bridges, which can be seen as symbols of a simpler, slower past, have become hazardous and time-wasting bottlenecks.

So we adapt. More cars, more trucks, more people, more commerce, more deadlines to meet, more products to deliver on time—all demand infrastructure improvements. Every one-lane bridge that is replaced is a necessity, but also another piece of old Costa Rica that disappears. Call it progress.