Sexual abuse, daily beatings, rotten food: The government of Nicolás Maduro on Monday denounced “torture” against Venezuelan migrants sent by the United States to El Salvador’s mega-prison for gang members.

These 252 Venezuelans were repatriated on Friday as part of a prisoner exchange between Washington and Caracas, which in return released 10 U.S. citizens and residents who had been detained in Venezuela.

Venezuelan Attorney General Tarek William Saab announced Monday that an investigation has been opened against President Nayib Bukele and other Salvadoran officials, accusing them of committing crimes against humanity.

The migrants are expected to begin reuniting with their families between Monday night and Tuesday. Since their return, they have undergone health exams, received new ID cards, and are being interviewed by the Public Ministry.

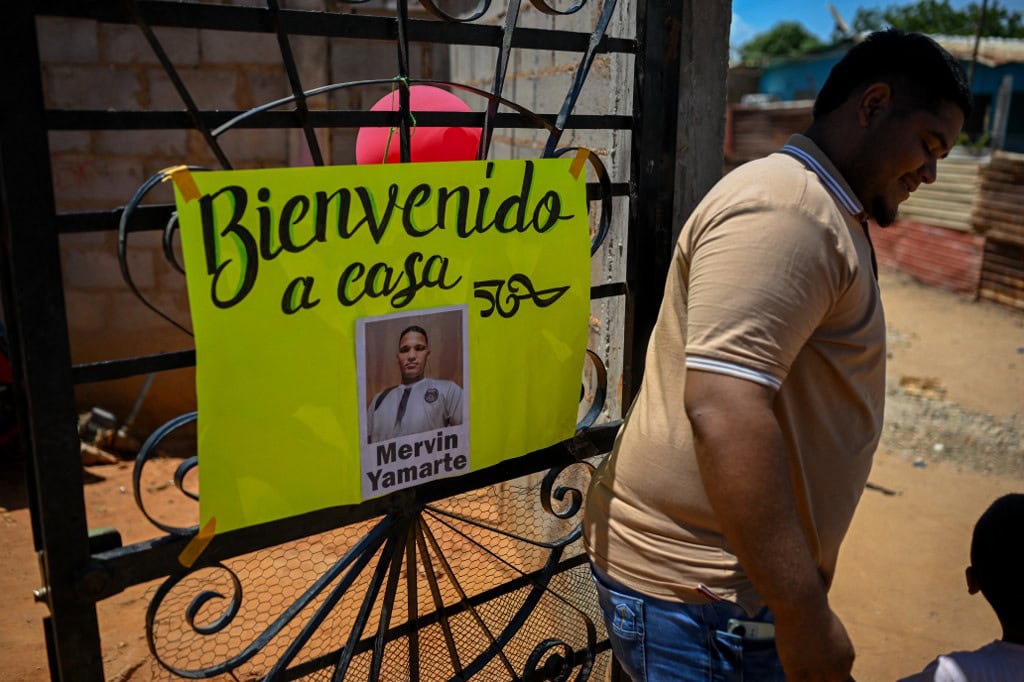

Like his compatriots, Mervin Yamarte spent more than four months in the Salvadoran mega-prison. His mother, Mercedes, has a celebration planned for him in the Los Pescadores neighborhood of Maracaibo in western Venezuela. She’s waiting with balloons, signs, and food.

During lunch on Monday, she got a phone call. “Mother, it’s Mervin.” “I hadn’t heard my son’s voice in four months and seven days. Hearing him was pure joy — a happiness I can’t even describe,” Mercedes Yamarte said.

Publicity stunt

Saab shared testimonies from some returnees who showed bruises all over their bodies and marks from rubber bullets. One had a split lip, another a scar on his shoulder.

Andry Hernández Romero, a 32-year-old makeup artist and stylist, said in a government-released video that he was sexually assaulted while held at the notorious Center for Confinement of Terrorism (Cecot).

“We were subjected to torture, physical abuse, psychological abuse,” he said. “I was sexually abused by Salvadoran authorities.” Saab also described “isolation in inhumane cells” without sunlight or ventilation and “systematic attacks with rubber pellets.”

He said they were fed rotten food, given undrinkable water, denied access to lawyers, and cut off from family contact. However, Venezuela itself faces frequent accusations of torturing imprisoned political opponents and denying them the right to choose their own legal representation. The International Criminal Court (ICC) is investigating the Venezuelan government for crimes against humanity.

Amnesty International urged the Maduro government to “guarantee and respect the human rights” of the returnees, after it had just reported a rise in forced disappearances in the country last week. It also condemned what it called a “cruel publicity stunt” by the United States.

“None of these individuals should have been detained under such conditions,” said Amy Fisher of Amnesty’s migration division.

A separate plane carrying deportees arrived Friday as well, unrelated to the prisoner swap. Among the passengers were seven children who had been separated from their parents by U.S. authorities.

Power play

The United States, without presenting evidence, had accused the deported Venezuelans of belonging to the Tren de Aragua — a Venezuela-based gang that President Donald Trump declared a “terrorist organization” under a 1978 foreign enemies law.

Their release came through an agreement with U.S. representatives, finalized just hours before the exchange, according to Maduro, despite what he described as “last-minute maneuvers” by Bukele to block the migrants’ departure.

“You couldn’t stop the first plane, but for the second one, you parked cars on the runway,” Maduro claimed during his television show, “to provoke an accident or stop the flight.”

The exchange also included the release of another 80 Venezuelans detained in Venezuela, considered “political prisoners” by the opposition. The government, however, said their release was part of a separate internal negotiation process.

Opposition leader María Corina Machado called the event a “prisoner of war swap” and denounced new disappearances of political figures.