Pete Seeger, a 20th-century troubadour who inspired and led a renaissance of folk music in the United States with his trademark five-string banjo and songs of love, peace, brotherhood, work and protest, died Monday at a hospital in New York. He was 94.

His grandson Kitama Cahill-Jackson confirmed his death to the Associated Press. The cause was not reported.

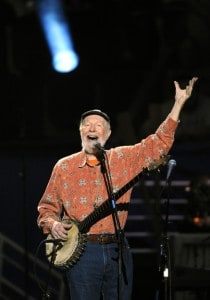

For more than 50 years, Seeger roamed America, singing on street corners and in saloons, migrant labor camps, hobo jungles, union halls, schools, churches and concert auditoriums. He helped write, arrange or revive such perennial favorites as “If I Had a Hammer,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” and “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine” and popularized the anthem of the civil rights movement, “We Shall Overcome.”

“Once called ‘America’s tuning fork,’ Pete Seeger believed deeply in the power of song,” President Obama said in a statement. “But more importantly, he believed in the power of community — to stand up for what’s right, speak out against what’s wrong, and move this country closer to the America he knew we could be.

“Over the years, Pete used his voice — and his hammer — to strike blows for worker’s rights and civil rights; world peace and environmental conservation. And he always invited us to sing along. For reminding us where we come from and showing us where we need to go, we will always be grateful to Pete Seeger.”

Tall and reed-thin, Seeger was a recognizable figure for generations of listeners. And with dozens of top-selling records and albums, he became one of the most enduring and best-loved folk singers of his generation. He also was one of the few remaining links to two of the 20th century’s early giants of American folk music: Huddie Ledbetter, the black ex-convict from Texas and Louisiana better known as Lead Belly, and Woody Guthrie, the minstrel songwriter from Oklahoma.

The classic song “Goodnight Irene” was a Lead Belly tune that Seeger adapted for the Weavers, a quartet he helped form after World War II. The 1948 recording by the Weavers sold 2 million copies.

From Guthrie, Seeger learned to express political and social criticism through music and song. Over time, dissent and left-wing expression became hallmarks of his artistic repertoire. During the anti-Communist “Red Scare” of the 1950s, he was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

“I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody,” he told the committee. “I have never done anything of any conspiratorial nature. . . . I love my country very deeply.”

Guthrie and Seeger had been colleagues in the Almanac Singers in the early 1940s and collaborated on union and labor songs. For the next half-century, Seeger changed the focus of his protest songs with the times to encompass social justice, civil rights, peace and disarmament, and environmental conservation.

At a Kennedy Center Honors ceremony in 1994, President Bill Clinton described Seeger as “an inconvenient artist who dared to sing things as he saw them.” The news media sometimes called him a “pied piper of musical dissent.” By the dawn of the new millennium, Seeger had become the widely acknowledged, if unofficial, grand old man of American folk music.

He regarded folk songs as music meant to be sung by crowds and bonded with audiences around the world by inviting them to sing along with him. During a performance at Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Concert Hall, he led an audience of 10,000 Russians in a four-part harmony of “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore.”

“I just tap out a beat, pick a few chords and say, ‘Come on, you folks know this old tune.’ Pretty soon the audience’ll be singing the song to me,” Seeger told the Chicago Tribune in 1994.

“You can’t sit idle at a Pete Seeger concert,” folk-music collector and performer Ralph Rinzler wrote in The Washington Post in 1972. “Audiences for 30 years have sung, clapped and risen to their feet with enthusiasm. Pete strides onstage, loosens his tie, picks the five-string, adding other instruments as he talks, spins yarns, preaches and sings songs of the nation’s and the world’s people — new ballads, old ones, lyrical laments and hard driving, keen-edged cutters.”

Whether leading a singalong of college students or performing in a formal concert, Seeger said, he tried to re-create the atmosphere in which his songs were first sung. He sang in a light, pleasing baritone. His goal, he said, was “to put a song on people’s lips, instead of just in their ears.”

He helped bring dozens of classics into the idiom of popular folk music. These included Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” and “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh,” Lead Belly’s “Midnight Special,” the folk song “On Top of Old Smoky,” the Hebrew song “Tzena, Tzena, Tzena,” the Zulu hit “Wimoweh” and the likes of “Turn, Turn, Turn,” “Guantanamera,” the nonsense song “I Know an Old Lady (Who Swallowed a Fly)” and “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy,” which became popular as a protest song during the Vietnam War era.

Chance and happenstance historically have driven the evolution of folk music, and so they did for many of the most popular tunes associated with Seeger. “If I Had a Hammer,” for example, began as a tune Seeger made up at the piano one afternoon in 1949 with Weavers colleague Lee Hays.

It was known in its original form as “The Hammer Song” and did not achieve popularity when the Weavers recorded it. But the lyrics drew the attention of federal investigators who during the 1950s thought that, used in songs, words such as “peace” and “freedom” were codes for left-wing subversives and communists.

Not until Peter, Paul and Mary recorded a revised version in 1962 did the song become a hit. It remained a centerpiece of Seeger’s concerts. “Very few people sing it as I originally wrote it,” Seeger said later. “I call this the folk process, and I’m delighted to see it carrying on.”

“We Shall Overcome,” for its part, was composed by a Philadelphia Baptist clergyman, C.A. Tindley, in 1903. The original title was “I’ll Overcome.” In 1945, an early civil rights activist, Zilphia Horton, heard striking tobacco workers singing the song on a picket line in Charleston, S.C. Horton taught it to Seeger, who made revisions and added a banjo part.

He, in turn, taught the song to folk singer Guy Carawan. After revising it further, Carawan sang it at a convention of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s. From there “We Shall Overcome” went around the world.

Peter Seeger was born May 3, 1919, in New York. His father, Charles Seeger, was a conscientious objector during World War I and an eminent music scholar, reportedly the first to teach a musicology course in the United States. His mother was a professional composer and violinist, and his stepmother was a writer of children’s books in which folk music figured prominently.

Political dissent had been a family tradition for generations. A great-grandfather was a 19th-century abolitionist. The World War I poet Alan Seeger, who wrote “I Have a Rendezvous With Death,” was an uncle.

As a child, Seeger accompanied his father on visits to friends in the city. Years later, he recalled hearing the folk song “John Henry” played on a harmonica by artist Thomas Hart Benton in Greenwich Village.

In 1935, Seeger attended a folk music festival near Asheville, N.C., with his father. There he first encountered the five-string banjo. He found that the instrument produced music that was different from the sound of the four-string, short-necked banjos commonly used by jazz bands in the 1920s. It became Seeger’s musical trademark (although he also played a 12-string guitar and wood flute).

He attended public schools in Nyack, N.Y., and boarding schools in Connecticut before enrolling in 1936 at Harvard University, where one of his classmates was John F. Kennedy. Uninterested in his studies and disillusioned by the social havoc wrought by the Depression, Seeger dropped out midway through his sophomore year. For a period during his Harvard years, he attended meetings of the Communist Party.

He worked briefly in the folklore archives of the Library of Congress, and for a time he traveled through the state of New York, painting watercolors of houses in exchange for room and board. But mostly he hitchhiked across the United States, mixing with like-minded political leftists, singing and picking up new tunes and techniques.

In the course of this odyssey, he once said, he learned “a little something from everybody,” and along the way he acquired a vast repertoire of ballads, spirituals and blues songs. Guthrie and Lead Belly were among the many musicians the young Seeger met in this period.

Years later, he said that one of his primary career achievements had been “to let a future generation know that such people as Woody and Lead Belly once lived.”

In the late 1930s, he met Toshi-Aline Ohta at a square-dance club in New York City. Her mother was American, her father Japanese. Amid the rampant anti-Japanese prejudice in the United States during World War II, the couple married in 1943 while Seeger was on furlough from Army service and had three children.

Toshi Seeger died in 2013. A complete list of survivors could not immediately be confirmed.

After leaving the military, Seeger formed the Weavers with three other singers, Hays, Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman. In the late 1940s and early ’50s, they sang on national radio and TV programs and in leading nightclubs and theaters. By 1952, sales of their recordings of such songs as “On Top of Old Smoky,” “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh” and “Goodnight Irene” topped 4 million.

Then, a magazine known as Red Channels named the Weavers — and Seeger in particular — as Communist Party sympathizers. There were calls for them to be blacklisted from professional entertainment engagements.

At the time, Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy, R-Wis., regularly made headlines with charges of Communist infiltration of government agencies, academia and the entertainment industry. In short order, almost all the Weavers’ nightclub, concert, radio, TV and recording engagements evaporated. Seeger’s public career was abruptly curtailed.

In 1955, the House Un-American Activities Committee began an investigation of Communist influence in professional entertainment and subpoenaed Seeger. He volunteered to discuss his music at length with the committee, and he offered to sing his songs. But he declined to answer questions about political associations or whether certain songs were sung at Communist gatherings, and he declined to invoke his constitutional right of protection from self-incrimination.

“I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this,” he said.

Convicted of contempt of Congress, he was sentenced to a year in jail. After a prolonged appeal process, the conviction was overturned in 1962 because of a technical flaw in the indictment. The government never retried him.

“I apologize for once believing Stalin was just a hard driver, not a supremely cruel dictator,” he told The Washington Post in 1994. “I ask people to broaden their definition of socialism. Our ancestors were all socialists: You killed a deer and maybe you got the best cut, but you wouldn’t let it rot, you shared it. Similarly, I tell socialists, every society has a post office and none of them is efficient. No post office anywhere invented Federal Express.”

With the resurgence of folk music later in the 1960s, Seeger’s music became popular again. His concert and recording opportunities swelled. In 1967, the Smothers Brothers negotiated a guest appearance for Seeger on their TV program, and he appeared in a series of one-hour programs on public television. By this time, the Weavers had long since disbanded.

During the 1970s, the ’80s and the early part of the ’90s, Seeger continued to make regular concert performances and recordings, and his compositions were recorded by other groups. But by the mid-1990s, his voice had grown weaker. He struggled increasingly to reach very high and very low notes.

In 1949, Seeger had bought 17 1/2 acres on a mountainside near the Hudson River in Beacon, N.Y., about 60 miles north of Manhattan. He built a log cabin and lived there with his family for several years before moving to a larger house on the same property. In his later years, he was active in environmental causes, including efforts to clean up the Hudson River.

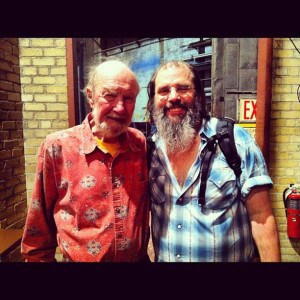

Until the end of his life, he remained a beloved figure. The broad public affection for him was on full display in 2009 when, at 89, he joined Bruce Springsteen in a rendition of “This Land Is Your Land” at a concert on the Lincoln Memorial during President Obama’s inaugural festivities. He was nominated for a Grammy this year in the spoken word album category for “The Storm King.”

“I call them all love songs,” Seeger once said of his music. “They tell of love of man and woman, and parents and children, love of country, freedom, beauty, mankind, the world, love of searching for truth and other unknowns. But, of course, love alone is not enough.”

© 2013, The Washington Post