When my wife and I moved to Costa Rica we were gloriously young and childless. Needless to say, childhood educational options were absent from our list of reasons of why it was a great idea to move to the tropical beach. As the years passed, beach bars and late nights gave way to family days at the beach and lathering babies in sunscreen. Eventually, it was time to consider what we were going to do with the kids when it came to education.

Our area of rural Guanacaste only had a few options for schools at the time, however we were always drawn to the educational model of La Paz Community School, a bilingual school that we had to come to know well through our community connections. Our two boys have been attending that school for around six years now and the experience has been overwhelmingly positive.

I can provide a long list of why I’m happy with the education that they’re receiving including a multicultural atmosphere, kids of all ages playing and learning together, and the fact that my older son had to bring special clothes to school the other day because he was going to get so deep into a pile of compost that his regular uniform couldn’t handle it. Recently, there was a specific moment that sparked some pride in the education my kids are receiving.

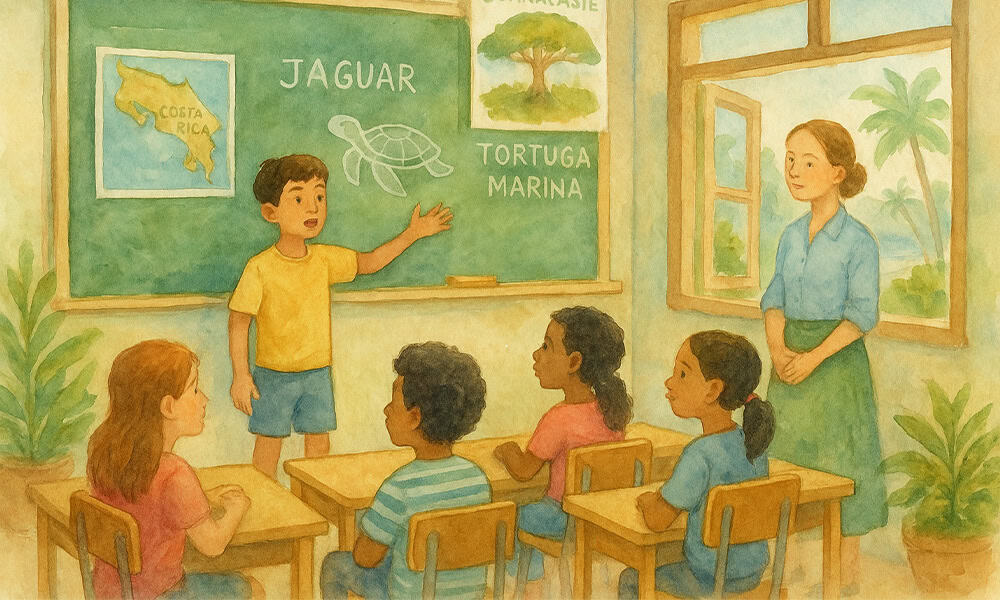

Last week I was invited to my older son’s class to give a presentation about wildlife and evolution. Part of the presentation was about jaguars and sea turtles. I’ll give you a quick synopsis – When jaguars were absent from the beaches of northern Guanacaste, raccoons and other nest predators used to tear through a significant portion of sea turtle nests, preying on the eggs.

After many years of successful conservation work allowed the jaguar population to grow, the jaguars began to eat some of the adult turtles while they laid eggs on the beaches, but they also had the effect of scaring away nest predators. So, in the end, even though some adult turtles get eaten, the effect of the presence of jaguars is a positive one for the sea turtle’s population. (Sorry, I had to sneak in some ecology talk)

I gave this particular part of my presentation in English, and though the students are bilingual, the teacher wanted to make sure that the native Spanish speakers fully understood, so he asked for a volunteer to repeat what I had said in Spanish. Several eager little hands popped up in response to this request, and the teacher happened to call on my son to complete the task.

He stood up from his little chair and effortlessly recited the whole story in Spanish. His accent sounded like a native Spanish speaker because he has been learning from native speakers his whole life. He used phrases I wouldn’t have thought to use, and I could tell he was concentrating only on the ideas he was portraying and not the technicalities of the language that he was using, which is a level of fluency that I sometimes struggle to reach with my own Spanish conversations.

At the end of his little speech he sat down, and I moved forward with my presentation like nothing remarkable happened but secretly my dad-heart swelled with pride. Anyone who has faced the challenge of mastering another language understands its difficulty, which makes it all the more rewarding to witness him thriving in a place that encourages his success.

About the Author

Vincent Losasso, founder of Guanacaste Wildlife Monitoring, is a biologist who works with camera traps throughout Costa Rica.