A Salvadoran man at the center of a heated US immigration battle could end up in Costa Rica if he accepts a guilty plea, according to court documents filed by his lawyers. Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who US officials wrongly sent to a harsh prison in El Salvador earlier this year, now faces deportation to Uganda after turning down the deal. This case highlights the Trump administration’s aggressive stance on migration and raises questions about Costa Rica’s role in accepting deportees from the US.

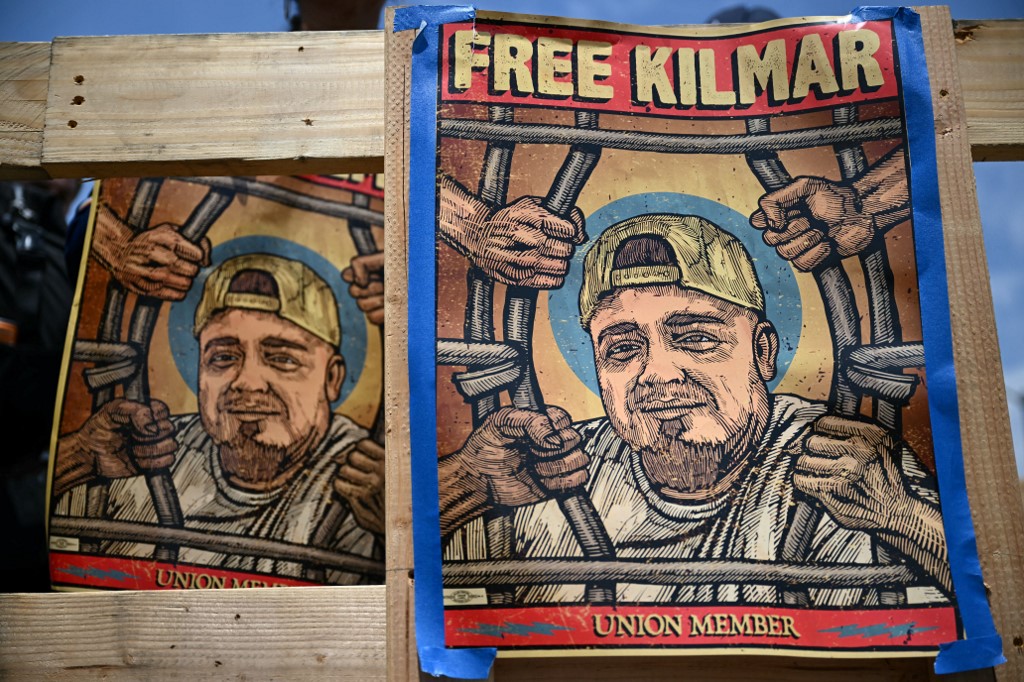

Abrego Garcia, 30, lives in Maryland with his family. He denies charges of human smuggling and ties to the MS-13 gang, which the government uses to justify their actions. Officials deported him to El Salvador in March, ignoring a court order that blocked such a move. He spent months in a maximum-security prison there before the US Supreme Court stepped in and ordered his return in June. Back in the US, authorities arrested him right away on the smuggling charges.

A federal judge in Tennessee released Abrego Garcia on Friday after more than 160 days away from his family. But less than a day later, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) told his lawyers they plan to deport him to Uganda as early as Monday. His team calls this a punitive tactic to force a guilty plea.

The plea offer came Thursday: stay in custody, admit to the charges, serve any sentence, and get deported to Costa Rica instead of El Salvador or elsewhere. Court filings include a letter from Costa Rican officials confirming they would accept Abrego Garcia and let him live here legally. He rejected the deal, prompting the Uganda threat.

This development pulls Costa Rica into the spotlight. Our country has long served as a safe haven for migrants fleeing violence in Central America. With stable politics and a focus on human rights, Costa Rica hosts thousands of refugees from Nicaragua and other neighbors. Accepting someone like Abrego Garcia fits that pattern, but it also tests our resources.

Costa Rican migration authorities have not commented publicly on the letter or the case. Still, the agreement shows close ties between San José and Washington on immigration matters. The US often works with regional partners to handle deportees, and Costa Rica has cooperated in similar situations before.

Critics in Costa Rica worry about the implications. If the US starts sending more people here under plea deals, it could strain public services already stretched by recent migrant waves. Local groups like the Defensoría de los Habitantes have raised concerns over housing and job access for newcomers. One advocate said, “We support refugees, but we need clear plans to integrate them without overwhelming communities.”

The Trump administration defends the approach as part of a broader crackdown on illegal migration. Supporters see it as tough enforcement, while opponents label it as overreach that ignores due process. Abrego Garcia’s lawyers argue the Uganda deportation aims to coerce him, calling it “vindictive” and against the law.

For us here in Costa Rica, this story serves as a reminder of our position in regional migration flows. As the US pushes harder on borders, countries like ours may see more requests to take in deportees. Whether Abrego Garcia ends up here depends on his next moves in court.

His team filed to dismiss the charges Saturday, citing government misconduct. A hearing could come soon. Meanwhile, he reunites with family in Maryland under the shadow of possible expulsion.