Anyone who’s done a lot of journalism work in Latin America in the past 30 years has likely bumped into the late John Ross at some point. I met him in the back of a cattle truck in southern Mexico in 1996, fresh out of a two-week mud fest in the jungle at the Zapatistas’ first Encuentro Intergaláctico against neoliberalism.

Barely in my 20s, the encuentro with the Zapatistas in Chiapas’ Lacandón jungle was transformational: I got to hear the great Uruguayan novelist Eduardo Galeano speak to fellow admirers inside a rain-soaked hut, and I was enthralled by a Silvio Rodríguez song for the first time. (“Sueño con serpientes,” played on an old cassette recorder someone brought into camp. I wrote it down.)

But Ross was surly in the back of that truck, maybe because it had rained nonstop for two weeks and we had been buried up to our knees in mud; or possibly because on the final day – the only time the sun came out – Subcomandante Marcos paraded into camp on horseback and accused us all of being whiny bourgeoisie. I was too intimidated and exhausted to ask Ross what his beef was.

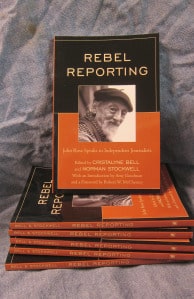

A new collection of Ross’ writings edited by Cristalyne Bell and Norman Stockwell, called “Rebel Reporting,” features lectures for journalism students, in-depth reporting and biting poetry. In the book, the late rebel reporter Ross, who died in 2011, describes the encuentro as follows:

In 1996, the Zapatistas called a conference in the middle of the Lacandón jungle ‘In Defense of Humanity and Against Neo-Liberalism.’ The event was called the ‘Intergaláctica’ and people from all five continents (and maybe some from other planets) came and danced in the mud. It was at the Intergaláctica that I first understood what the World Trade Organization was all about. The meeting was really the seedbed for Seattle.

In hindsight, Ross could have just been angry about the way the world was going, and his mind probably was racing about what he was going to do about it.

Context and oficio.

These are two of Ross’ words that kept springing to mind as I read “Rebel Reporting,” which started as a series of lectures he delivered to budding journalism students at colleges and universities in the United States and was later compiled and published posthumously by Stockwell and Bell.

In Seattle, three years after the first Zapatista encounter, Ross notes that 60,000 people showed up to a protest that exploded into a global happening, culminating in the Occupy movement more than a decade later.

Here’s how Ross describes the word “oficio” to his audience of journalism students:

The first thing you need to know is that you do not have a career in journalism. Forget about your career. You have an obligation—to tell the story of those who entrust you with theirs, to tell the truth about the way the world works. In Mexico, we call this an ‘oficio,’ an office of responsibility to the community. You serve the community. You don’t have a career.

In the editor’s preface, Stockwell talks about context:

“On one trip, in 1994, John shared a wealth of details about an armored car robbery that had just taken place that morning, including the personal history of the military officer who had been shot dead during the heist. ‘It’s all about the context,’ Ross said. ‘I can’t move anywhere else and throw away all those years of context.’”

In the 21st century era of quick-to-forget digital media, stimulatory hits and clips, putrid punditry and parachute reporting, context has become somewhat of a lost responsibility. For me, it’s an anchor that prevents us from drifting too far out in that sea of information with no way to order it, interpret it, and make decisions.

Ross’ era of anti-globalization protest and reporting marked the end of a period where things seemed more clearly defined, where evil in the world was quite tangible, and once a conscientious decision was made to fight it, it wasn’t too hard to figure out how. Today’s digital landscape seems much more gray. Finding that anchor – the context – becomes crucial, and it boils down to finding your principles as a human being.

As Ross said, to be a rebel reporter you have to go to the place where it happened — “ir al lugar de los hechos.”

Debates about objectivity aside, if it weren’t for people like Ross, we might easily have forgotten people like South Korean farmer Lee Kyung-hae, who at a 2003 WTO demonstration in Cancún, climbed a barricade and stabbed himself in the heart, the ultimate act of protest.

Ross, who was standing nearby, wrote about it in his poem “The Three Deaths of Mister Lee.” News stories about Lee’s suicide, which inevitably helped derail that round of WTO talks, have come and gone. But Ross’ poem – like his other poetry in this book – is timeless, helping to solidify one man’s personal struggle against the effects of globalization into more humanistic principles upon which we should all reflect.

He does the same thing with the story of Brad Will in part two of the book. If it weren’t for Ross’ detailed reporting and captivating prose, we might mistakenly remember Will as a reckless radical who went to Oaxaca and got himself killed.

But for Ross, Will, who filmed his own death at the age of 36 in southern Mexico during a long and bloody uprising in 2006, was the epitome of a rebel reporter, going to the place where it happened in order “to document the struggle for justice.”

In the forward to “Rebel Reporting,” media critic and University of Illinois at Urbana professor Robert W. McChesney noted that “John Ross practiced Jefferson journalism, covering revolutions, rebellions, and reality with the acuity of Tom Paine, the honesty of Albert Camus, the wit of George Carlin, and the prose of Jack Kerouac. In a sane world he would be a household name, and like Tom Paine his words would have moved a nation to greatness.”

—

“Rebel Reporting: John Ross Speaks to Independent Journalists” is on sale now just in time for the holidays. Click here to order.

The Tico Times recently spoke with “Rebel Reporting” editor Norman Stockwell, a freelance journalist based in Madison, Wisconsin, operations coordinator for WORT-FM Community Radio and a frequent contributor to The Tico Times.

Excerpts follow:

TT: Walk me through the process – how did this project get started?

NS: It’s a great and long story. John asked me at first to help him find a publisher for the book probably over five years ago. And the first thing we did was to share the manuscript with Bob McChesney, who is a professor of journalism at the University of Illinois and founder of an organization called Free Press, which does a lot of advocacy for independent media. And so Bob read it and really liked it and wrote a letter of introduction to a publisher and we sent it in. It didn’t get anywhere.

Then John had a bout of liver cancer, which came back in late 2010, and at that point, he moved down to Mexico where he could spend his last days in the place that he loved. He passed away on Jan. 17, 2011.

I immediately contacted his closest friends and family and said, “John left me this manuscript, and I really would like to move it forward toward publication.”

And then began the process of contacting publishers. I contacted well over a dozen publishers, all of whom were ones where either I knew someone, an editor, or I had a letter of introduction from one of their other published authors. And everyone turned it down for a variety of reasons, partly because the publishing business is hard nowadays.

And so, I was almost giving up on anybody ever accepting this manuscript. And then I stumbled across a book that was talking about media coverage of the Iraq war, and I said, well, this is interesting, these guys might be interested in this, so I sent a proposal to them and they got back in late 2014. And they said yes, they’d like to publish it, and they sent me their guidelines. …

I began the process of assembling the manuscript for publication, which meant editing and footnoting and so on.

Before John moved back to Mexico, he was living in the U.S.?

He spent a good part of his life in Mexico and part of it in San Francisco, his sort of two adopted homes. John was originally from New York, but he moved to Mexico in the late 1950s and lived there on and off and in San Francisco on and off for the rest of his life.

He was living for most of the time in Mexico City. Since the earthquake he was living in the Hotel Isabel in downtown Mexico City, in the Centro Histórico. And he had lived in that hotel almost since the day he moved there to cover the devastation after the 1985 earthquake.

And so in tribute to that we’re going to be doing a book release event in the lobby of Hotel Isabel on Jan. 2 in Mexico City.

How did you and John meet?

I chronicle this a little bit in the editor’s preface, but basically I came to know his work back in the late 1980s covering the theft of the Mexican presidential elections in 1988. John and I actually didn’t meet until a couple of years after that. I was traveling through Mexico in 1991 and we got together there and had dinner and became correspondents and friends for the next couple of decades.

I got to host him here in Madison a number of times when he would be on book tours with his various publications over the years: his book on the Zapatistas called “Rebellion from the Roots,” and then later his own autobiography, “Murdered By Capitalism,” and his book on Mexico City, “El Monstruo,” and also some others in between.

We would usually set up a series of things when he came to town. They would include lectures at some of the various educational institutions here in Madison, the university, Edgewood College, MATC, which is the community college, and he would also do some kind of public presentations either at a book store or coffee shop, and he would also do something on the radio.

And so that would happen every few years through the late 1990s and 2000s. And when I was in Mexico, I would always make a point of visiting him. We were together during the Mexican elections in 2006, and he also came to the States during the Republican Convention of 2004, and we went into the convention together to cover Bush’s – whatever you call that speech that candidates give when they already know they’ve got the nomination.

Then we were together in Cancún at the WTO protest, covering things both inside and out – from inside the press center in the actual WTO meetings and out in the streets where the real action was happening. Although in 2003 there was a lot of action inside as well, because that was when the countries of the south actually stood down the WTO pretty effectively.

So John and I had worked together on many different projects like this, and I would always help him to set up these lectures. Several of the lectures in the book he gave here in Madison to different classes of students, and two of them were attended by a young journalism student named Cristalyne Bell, who also has lived in Costa Rica. She was living there at the time when we started assembling this book.

For people who may not have read John’s writing yet or bumped into him at one of these global events, who was he, and why was he so important in the modern journalism landscape?

John was a radical journalist from the start. He believed that the role of a journalist was to give voice to the people at the bottom, whose stories most needed telling; that you don’t sit there and be a stenographer to the people in power and dutifully copy the press releases. Rather, you go to the people that are being affected by the policies, and you get their stories and you share that with an audience. And that’s the essence of what John – and I as well – felt journalism is all about.

And so, he would always go to the regular everyday working people in any situation and he would tell their stories, because they had no other way to get their voices out, whereas the rich and powerful have many ways to get their stories out.

So, from the beginning he was committed to Mexico, originally to live, and then later he was working for a newspaper in Peru, and then he went in 1985 from Peru to Mexico City right after the earthquake to cover that for People’s News service, among others.

He was, again, telling the stories of the people who were affected by that tragedy. He moved into downtown Mexico City to live among the people and tell their stories.

The title of the book is “Rebel Reporting.” Why is it called “Rebel Reporting” instead of just “reporting?”

John says in the lectures that what he wants to talk about is “rebel journalism,” although he says he doesn’t like the word journalism even, because it sounds so snooty, and so he changes it to “reporting,” but the idea is reporting basically about rebellion, but also reporting in a way that is rebellion against the mainstream attitude of what journalism has become in the late 20th and early 21st centuries – as someone else said, becoming “stenographers to power.” This is not about that, this is about telling real people’s stories.

So rebel journalism he lays out during the course of these lectures the principles that guide rebel reporting. One of them is to actually go there and feel and live in the place where you’re reporting on and the places where the people are being affected. Also, just that the notion of journalism as a moral obligation, not just a thing that you do to make a living.

He talks about the concept of being actively involved, not just being an outside observer, but actually being a part of the people’s lives that you’re reporting on.

Another interesting part of the book is his family’s history. It’s not as if he suddenly discovered journalism, he actually was born into a family surrounded by writers and critics and people whom one might describe even back then as rebel reporters.

John grew up in a radical family in New York City and was very much a part of the movements for social change of the mid-20th century and forward. And so he came to his work with a deep connection to people working to build a freer, more just society. And he was exposed early on to a lot of radical activists. He refers to himself as a “lesser Beat poet.” He was connected to the last years of the Beat Generation, and that influenced a lot of his poetry. He was involved in a lot of political movements, and of course in the anti-war movement as he chronicles somewhat in the book.

He was imprisoned for refusing the draft, he was involved in various social movements that resulted in him getting his eye damaged in a protest, which continued to trouble him for the rest of his life. He was very active in the protests against the most recent Iraq war, and continued to use his pen and his voice to oppose militarism, to oppose the actions of the powerful against the weak throughout the world.

In the forward, Robert McChesney paints John as a self-described “enemy of J-School journalism,” comparing him to Tom Paine, Albert Camus, George Carlin and Jack Kerouac. Those are some pretty big names.

I also love Mary Jo McConahay’s quote, basically that he’s part Jack Kerouac, part Roque Dalton, part Che Guevara and part Hunter Thompson.

I would add Werner Herzog. Reading the second part of the book on Brad Will is like watching a Herzog film – it gets at the deeper truth of things.

The Brad Will story, the reason it’s paired together with the lectures is that, on the one hand, he’s talking about rebel reporting in his lectures to college students. But in the second half, we show two things. One, we show how it’s done. He chronicles his dogged search for the truth in the death of Brad Will, and how he went to all these places and interviewed all these people that were involved in order to get to the roots of that story, and then also, he chronicles Brad himself as an example of somebody who was committed to this philosophy of rebel reporting – not from reading John’s work or anything else, but from living with and experiencing the lives of these people affected by the policies of the various governments, the Mexican government in the case of Oaxaca, but other stories in there as well.

And so what you see is that the two pieces, even though they’re totally separate things, go together very well. Brad Will died in Oaxaca while John was giving these lectures for the first time in San Francisco. And Brad had connections here to Wisconsin, he had connections to the northern suburbs of Chicago, and so a lot of John’s research happened here in Madison. That’s the connection I think for that piece of the book.

Tell me about John Ross the poet. There’s a lot of his poetry in this book and it complements the prose, particularly his chronicle of “The Three Deaths of Mr. Lee,” which talks about Cancún.

Yeah, of course with Mr. Lee, we were right near him when that happened in Cancún, and my colleague Kata Mester from Free Speech Radio News had actually interviewed him, the Korean farmer Mr. Lee, not long before he took his life. So that was a very powerful moment in those protests in Cancún.

Going back to John’s early, early history, he grew up immersed in poetry and literature and the world of radical poets raising their voices against injustice, and that colors everything he then did moving forward with his own poetical work. He published chapbooks of his poetry, and he did poetry readings as well as his journalism work. He did some here in Madison, he did a lot in San Francisco, and his lecture about “our words are our weapons” talks about that, about the importance of language both to paint a picture and also to communicate to people in a different and deeper way. I think poetry brings home a message in ways that a simple paragraph of text cannot do.

Poetry is a very powerful tool. Speaking of tools, the book also includes an extensive resource list for journalists at the end. There’s a lot of useful stuff there.

That was my intellectual contribution, I guess, to the book. I felt that we needed to have something that would take this and make it more than just something for students to read, but also something that would give them some of the tools and resources they would use when they actually embark on this career. And so Catherine Komp, a colleague from Free Speech Radio News, had put together initially a little training document that she sent around, and I wrote to her and said, “Catherine, this is wonderful, can I use this in this book?” and she said, “Yes, of course, please do.” And then I got another WORT intern, Laura Brickman, who is now in grad school in journalism at Columbia, to help me go through and identify links and resources, and then write those little descriptive paragraphs, and so it was a collaborative project, and the result is a very useful set of tools.

Now, because it’s on the Internet, some of those links will probably change over time – some of them actually changed already – but whenever we come out with the electronic edition of the book, they’ll be updated.

One of the interesting things about this book, in hindsight, there are some deeper, fundamental issues here. It’s easy to get distracted and lose your way in the digital landscape. I feel like we tend to get lost about what really has meaning when we’re choosing our stories and how we report them.

John talks about the responsibility of the reporter. He talks about it being an oficio, that you have a responsibility to do this work. And I think that holds true no matter whether you’re writing with a pencil on a pad of paper as John did, or whether you are typing on a keyboard into a computer, or for that matter, talking into a microphone or speaking into a camera – it’s that responsibility that’s so important, and that’s timeless.

What he’s saying in the book is that no matter what the technology, no matter what the medium, and no matter what the delivery mechanism, it’s about the responsibility you have as a journalist to tell people’s stories and to get those stories out there.

Nowadays, you’re right, the Internet, most people are consumers of media, they have media washing over them and they’re not participating as much perhaps as they might have been in the days when you actually had to pick up a newspaper and turn to the page to find the article, but the responsibility of the journalist remains the same. It’s an interesting side note that this 24-hour media cycle, when we get all these, every bit of detail, as Amy Goodman says often, we have these journalist pundits who tell us so much about so little, and what we really need are those little stories of the everyday people to really understand the impacts of these issues and these policies, and that’s what the rebel reporter does, tell those stories and help people to get a better understanding, a better picture of the actual effects of these things that are being done in our name by our governments.

I’ve had conversations with people who could be described as rebel reporters, who go to where the stories happen, they bring them to the surface, they get them published, and then the stories aren’t read, they don’t get traffic. What can we do to make sure that not only do we go to the source, but also to make sure people see the work?

I have to say that things like The Tico Times are doing a wonderful job of getting those stories out, because you do distribute things through the Web, through Facebook, so you do get it out, and I think all of us in the world of independent journalism need to be conversant in this and not say, “Oh, I’m only going to have my stuff printed in The New York Times.” You need to use all of the different tools in your toolbox to reach a broad audience, and you need to reach them where they are able to receive the information, whether it be a fax or a printed page, or multimedia websites with video and audio clips.

You’re taking the book on tour – tell me about that.

So the book officially launched on Dec. 15, and the first event [was] right here in Madison, Wisconsin, where I live. From there we go to New York and then Mexico City, Seattle and San Francisco, with other possible events in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Chicago and hopefully San José, Costa Rica.

The book can be ordered directly from the publisher at Rowman.com and also from the many different online retailers in the world of the Internet. And it can be purchased in local bookstores. If your local bookstore doesn’t have it, please ask them to order it. And finally, libraries. Library budgets are thin nowadays, so if people request a book they will make sure to get it, and I hope people will get this out in as many different ways as possible.

When the first printing sells out we’ll look at doing an online electronic version, but that won’t be right away.

One last thing, I wanted to jump back to the Intergaláctica and how that and the first World Social Forum really connected with Seattle. Seattle was here in the States, and we didn’t know the word globalization. It really came from you folks from the global south that we began to have an understanding of that, and the fact that people were able to come together in Seattle – 60,000 people – to protest the World Trade Organization, it was a major game-changer, certainly for the global north in terms of its understanding of the role of these trade agreements and so on. And it also became the fodder for the creation of the World Social Forum movement – in coming out of Seattle you had the first World Social Forum in Brazil, created to be a counterpoint to the World Economic Forum, and then going on for the next 15 years since then with regular gatherings of people from civil society, organizations around the world coming together to showcase alternatives to corporate capitalism.

Congratulations, the book is a wonderful read and should make people think.

Thank you, I’m really very pleased with it. For me it’s sort of the culmination of five-plus years of work doing what was an oficio for me to get this work of John’s into the hands of a whole new generation of independent journalists.

—

Read more of Norman Stockwell’s work in The Tico Times:

The pen against the swords: Author Jorge Galán seeks asylum after threats in El Salvador

Miguel Facussé is dead: What does that mean for the people of Honduras?

Archbishop Óscar Romero: Another step on the path toward sainthood

The exposure of Eugene Hasenfus

PHOTOS: Esquipulas II – 5 presidents who came together to choose their own path

Reviving the messenger: Gary Webb’s tale on film

Remembering the Jesuits: Seeking justice in El Salvador after a quarter-century