On Aug. 7, 1987, five Central American presidents signed a peace accord known as Esquipulas II, named after the city in Guatemala where the first round of meetings had taken place the previous year.

The accord, signed by Costa Rica’s Óscar Arias, Guatemala’s Vinicio Cerezo, El Salvador’s José Napoleón Duarte, Honduras’ José Azcona and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega, included a number of provisions for cooperation between the five countries, and most notably, it called for an end to support for “irregular forces” by all of the signatories.

This provision was aimed at ending the Contra war in Nicaragua and included an offer of amnesty to those Nicaraguan Contra fighters who chose to lay down their arms and reintegrate into society.

This groundbreaking document was later used as a basis for other peace agreements in the region. The process was also important because the U.S. government, the main funder of the Contra forces, was actually pushed out of the negotiations and had little influence over their outcome.

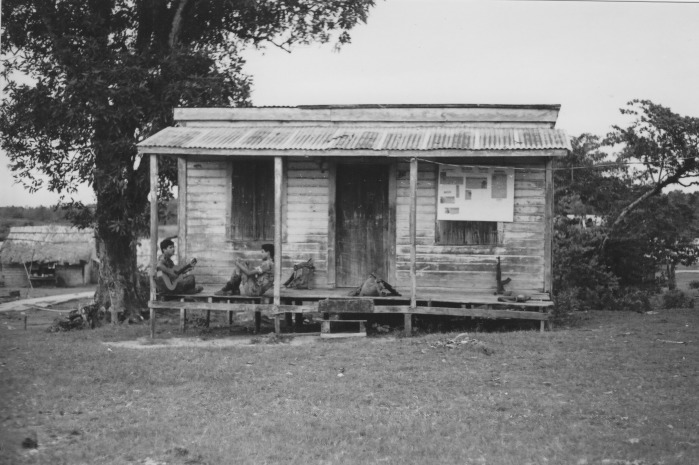

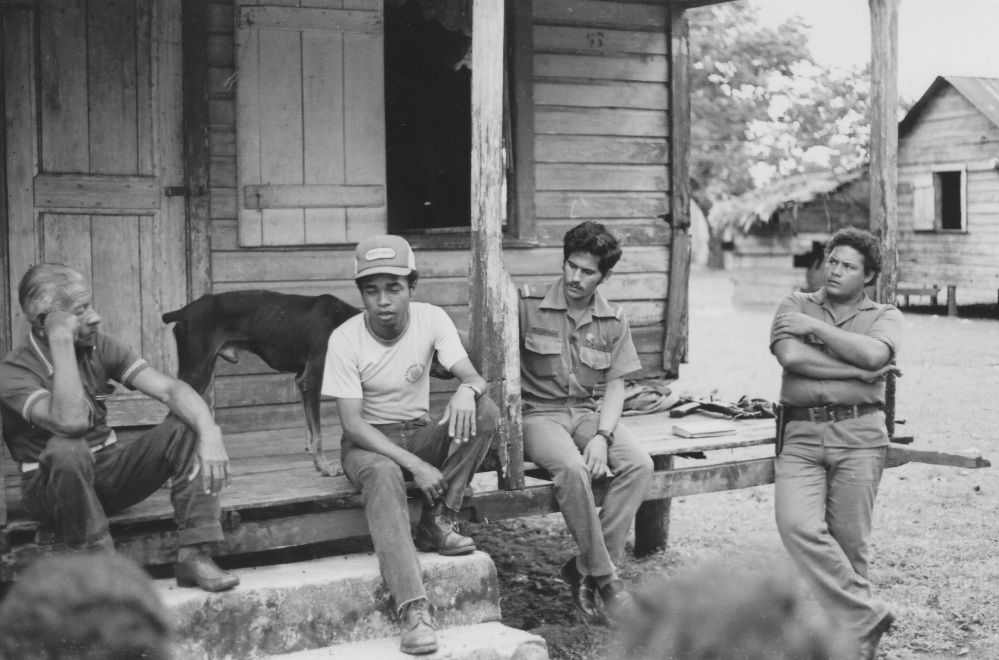

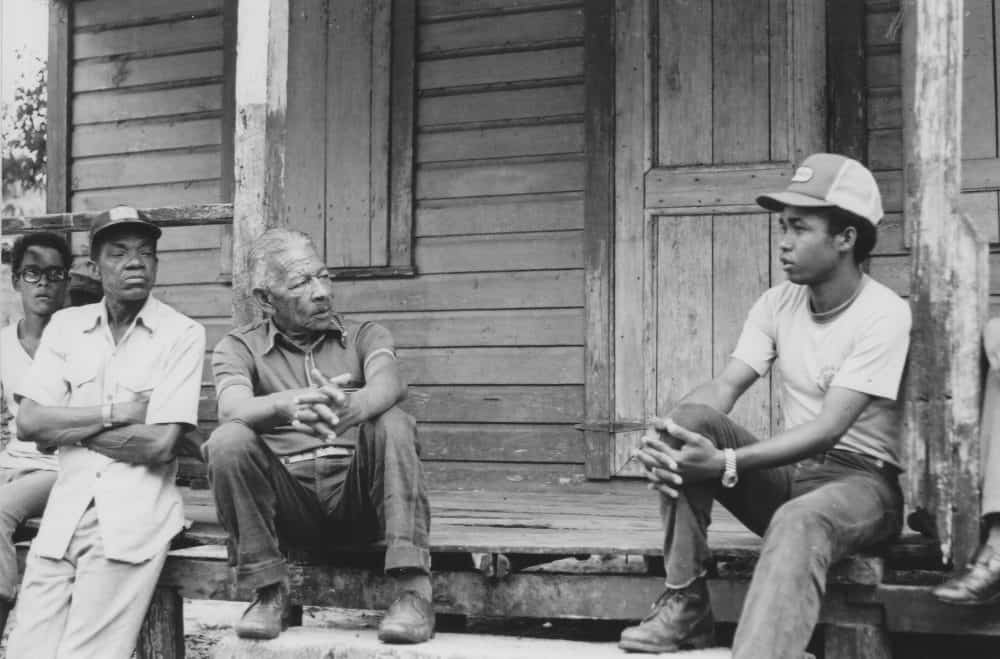

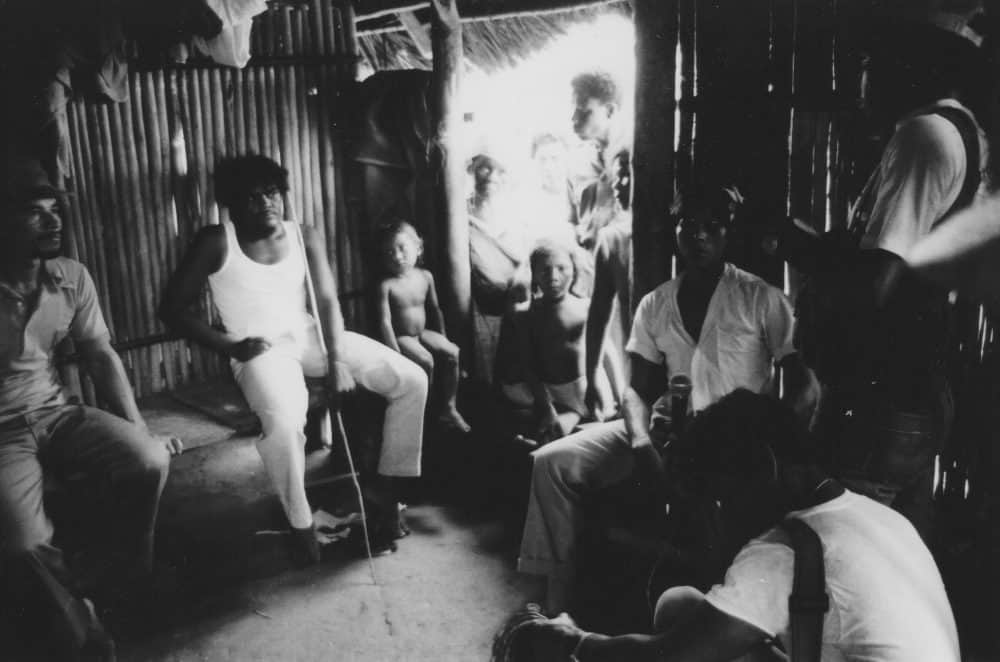

In October of that year, a small group of us traveled by panga (small, motorized boats) up Nicaragua’s Atlantic Coast to interview Contras who were surrendering and returning to their communities. We traveled from Bluefields to the coastal towns of Haulover, Pearl Lagoon (Laguna de Perlas), Brown Bank, La Fe, Orinoco and Tasbapauni, in each location meeting with members of local Peace Commissions and Sandinista military and political officials.

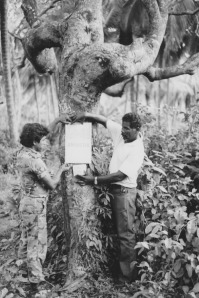

In some areas we accompanied local residents as they affixed posters to trees in the surrounding bush areas that proclaimed “amnistía” and showed a photo of the five presidents at the signing ceremony of Esquipulas II in Guatemala City.

I carried two Pentax K1000 cameras (one with black-and-white film, one color) and an old, brown Marantz PMD200 cassette recorder. But my load was light compared to the Bluefields regional TV crew with their Sony 3-tube analog video camera, 3/4” tape deck, tripod, cables and mics. We spent nights bunking with Sandinista patrols and sharing their scant provisions. A short video from that trip can be found on YouTube:

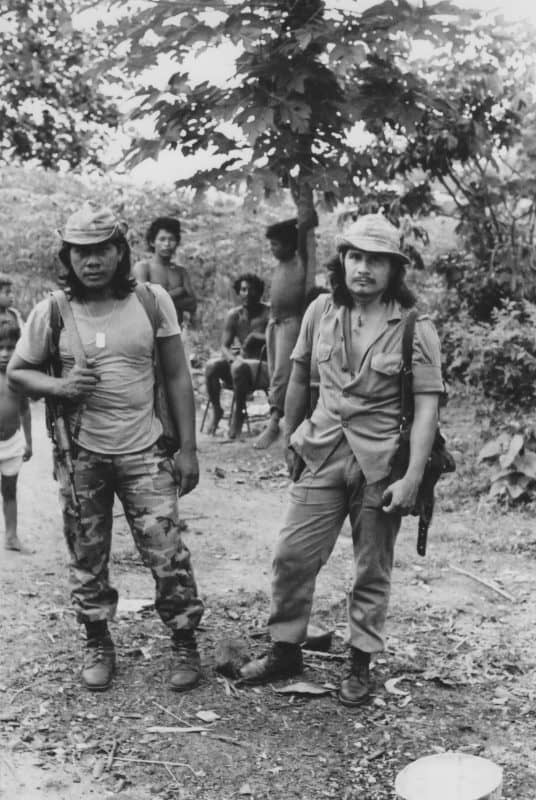

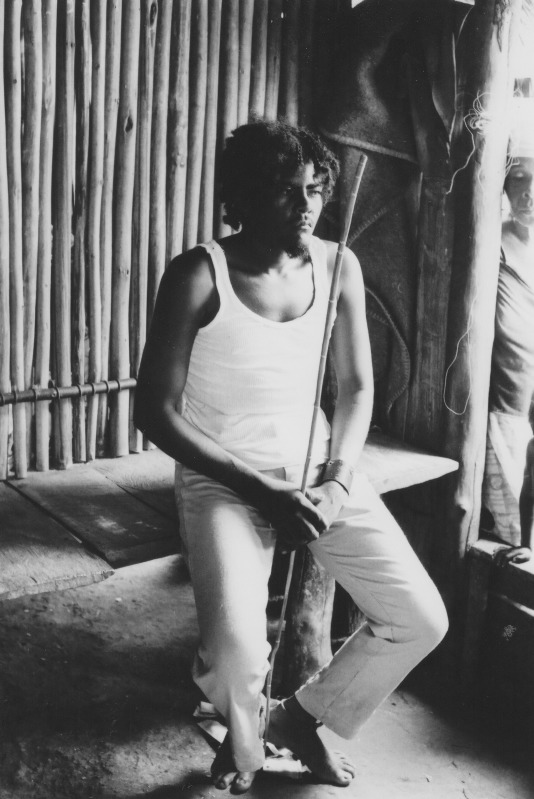

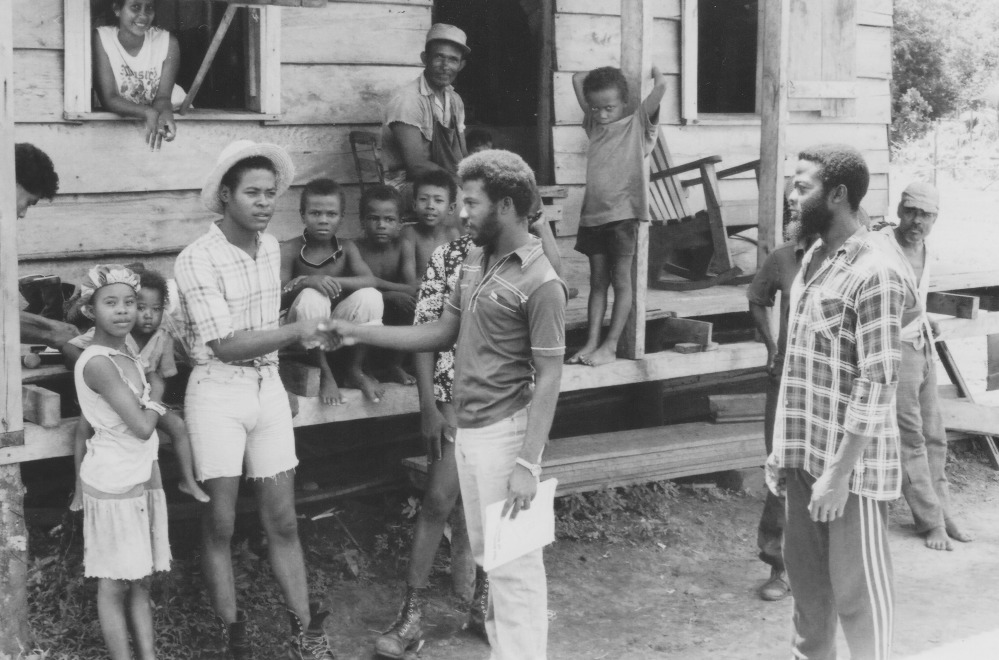

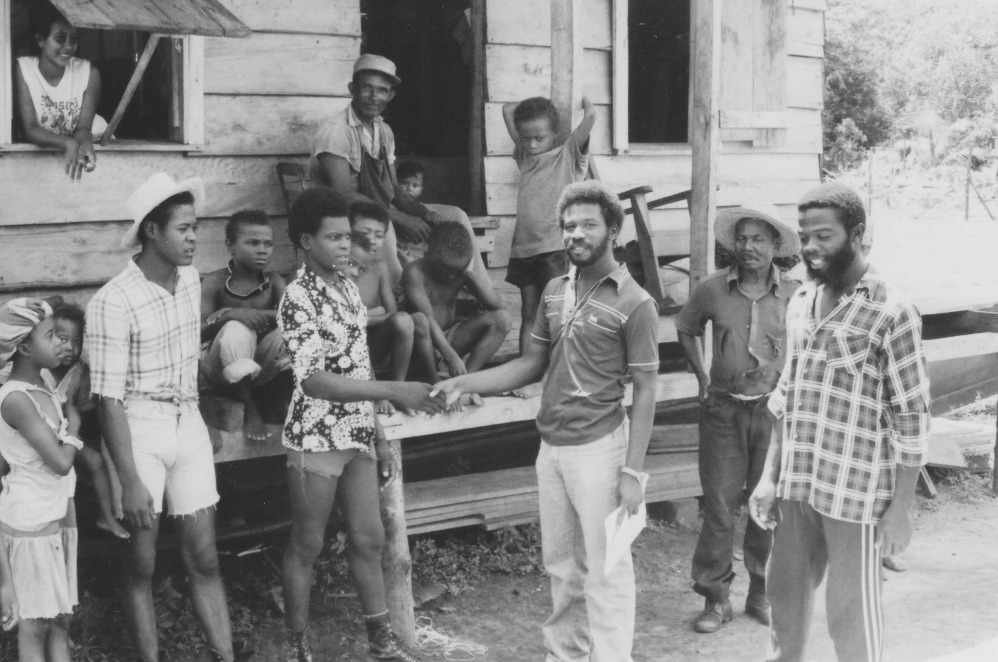

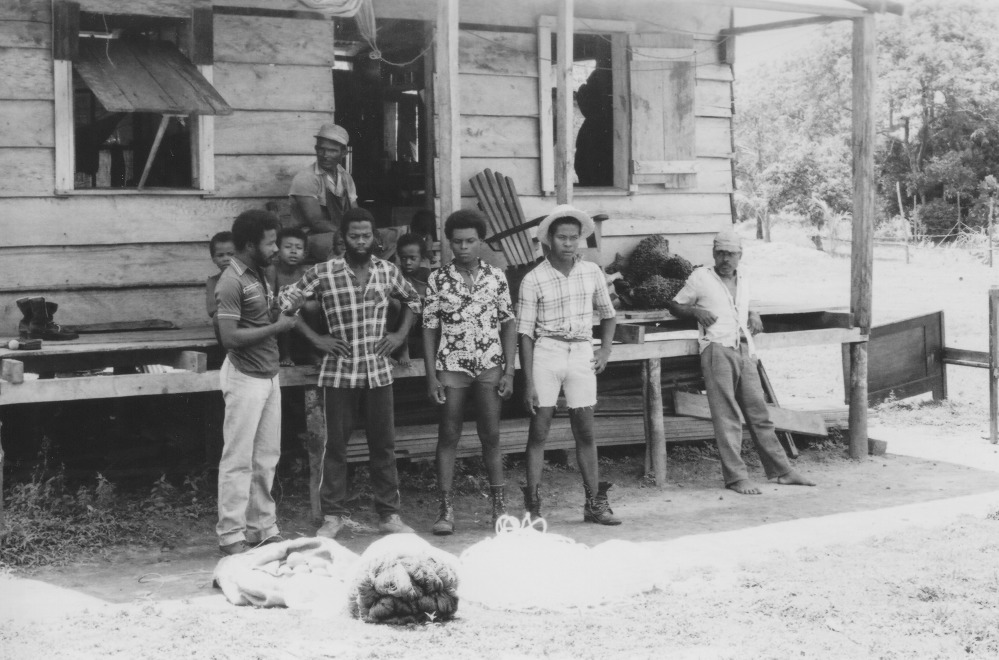

In a novel – and seemingly successful – approach, the local political leadership provided every pair of returning Contras, called “desalzados,” with a fishing net (a venture funded by donations from the government of Norway). The idea was to give the returning youth a means of employment and a way to reintegrate into the life of their community. Many, it seemed, had joined the Contras because it provided a way out of unemployment, and they were each given a backpack!

The desalzados, mostly young men in their late teens, told of being led into the bush and then mostly abandoned by their commanders. “Sometimes we eat, sometimes we don’t eat,” said one young man to me. They had very little direction and often turned to staging raids on their own communities in order to get needed provisions.

Many kept secretly in touch with their families when they could; others had no contact and now returned to parents who had not known if they were still alive. All of them seemed, at least at this moment, glad to have put this portion of their lives behind them. However, none returned with weapons. Many may never have had one. Others, one local resident told me, “Probably buried them somewhere, just in case they want to go back.”

It was a turning point in the Contra war in many ways. Although later that month, I was to travel through one of the largest Contra offensives to date on the Rama Road, overall, the exposure of the Iran-Contra Affair in 1986, combined with international recognition of corruption within the leadership and human rights abuses by Contras hastened the decline the Contras as a military force.

In 1990, it was an electoral defeat – not a military one – that unseated the Sandinistas from power. The February 1990 loss for Daniel Ortega came in the wake of years of a harsh economic embargo by the United States combined with a U.S. military invasion of Panama in December 1989, which further cut off the flow of consumer goods to the starved Nicaraguan economy.

Today, 35 years after the Sandinista victory on July 19, 1979, Daniel Ortega is again president of Nicaragua. But both Ortega and the country he governs have changed a great deal since the hopeful days of August 1987, when the five Central American presidents joined together to thumb their noses at a U.S. president and seek to solve their own issues in their own way.

Following are more of Norman Stockwell’s photos from that era:

Norman Stockwell is a freelance journalist based in Madison, Wisconsin. He also serves as operations coordinator for WORT-FM Community Radio. Stockwell has reported from numerous countries in Latin America, including interviews on Nicaragua’s Atlantic Coast with Contras surrendering to take amnesty under the 1987 Esquipulas Accords. Read his excellent story marking the 30th anniversary of the La Penca bombing here.