In the history of Costa Rica, few expats were more influential than Tomás Povedano. Born and raised in Spain, Povedano enjoyed some stints in Ecuador before moving to Costa Rica and founding the National School of Fine Arts. He also illustrated the “Cartilla Histórica de Costa Rica,” a history manual used by nearly every young student in the country. He lived for nearly a century, and eventually died in San José in 1943.

But as a new exhibit at the National Bank Museums will attest, Povedano also invested in local money – by contributing his art to the design of paper bills. “Tomás Povedano y Los Billetes de Costa Rica” is a striking examination of Povedano’s art, vintage currency, and the nationalization of Costa Rican culture.

Upon close inspection, it is clear that Povedano’s artwork was 19th-century in character. His portraits are realistic, depicting important Costa Rican figures exactly as Povedano saw them. In a way, this is surprising: Povedano was a Freemason and Theosophist, occultist groups that employ heavy symbolism and secret meanings, yet Povedano’s paintings seem a far cry from “The Da Vinci Code.” His characters are buttoned-up and his palette is mostly earth-toned. What you see is what you get.

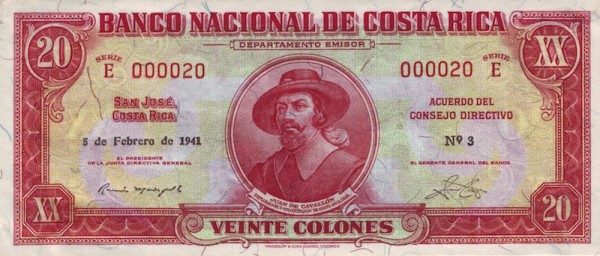

While Povedano seemed to live a fairly straightforward and industrious life, the exhibit explores how important the artist was to turn-of-the-century Costa Rica: By painting important figures in the nation’s history, Povedano helped an entire generation of schoolchildren understand their place in the world. When many of these paintings were adapted as plates for printing money, the artist helped establish the colón as contemporary currency. For years, nearly every Tico alive carried Povedano’s artwork in their pockets and purses.

The most gripping of these works was the painting “The Rescue of Dulcehé.” According to legend, Dulcehé was an indigenous princess who was kidnapped by a rival tribe. When her family complained to the Spanish colonists, a garrison of soldiers invaded the village and rescued Dulcehé. In the painting, she is pictured bare-breasted and afraid, while an armored musketeer gently offers his hand. The painting was never finished – some figures are only white outlines – so fellow artists had to imagine the completed work in order to decorate the two-colón bill.

It is fitting that the Central Bank Museums would focus on money, but the exhibition is also a rare glimpse at an under-appreciated artist, someone who helped shape Costa Rica in both creative and practical ways. While Costa Rica’s current cash has some beautiful images, such as sloths, sharks, and trees, Povedano’s art predated the modern nation of 1949 and shows what images were important to the people of that era. To them, the face of a conquistador (Juan de Cavallón) was more meaningful than the face of a spider monkey. It is a strong reminder of how far the country has come.

More provocative still, Povedano is often described as a “Costa Rican artist,” even though he was 52 when he finally arrived in the country. However he is remembered in Spain, Povedano left a profound legacy in Costa Rica. Sometimes, nationhood is about where you’re born. Other times, home is where the corazón is.

“Tomás Povedano y Los Billetes de Costa Rica” continues through Aug. 1, 2015 at the National Bank Museums, downtown San José. Open daily, 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. 5,500 ($11). Info: Museum website.