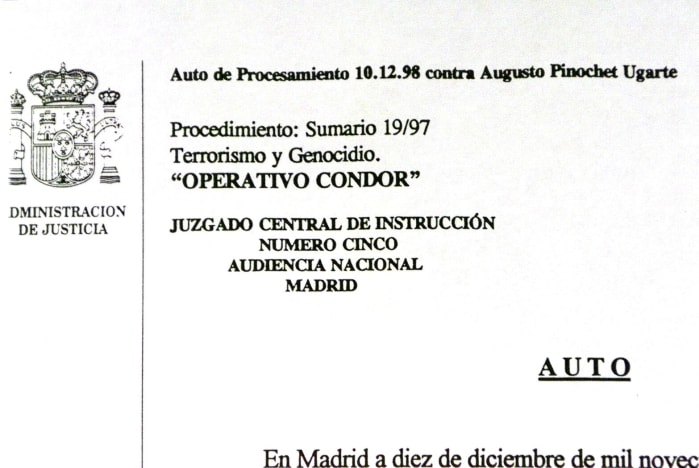

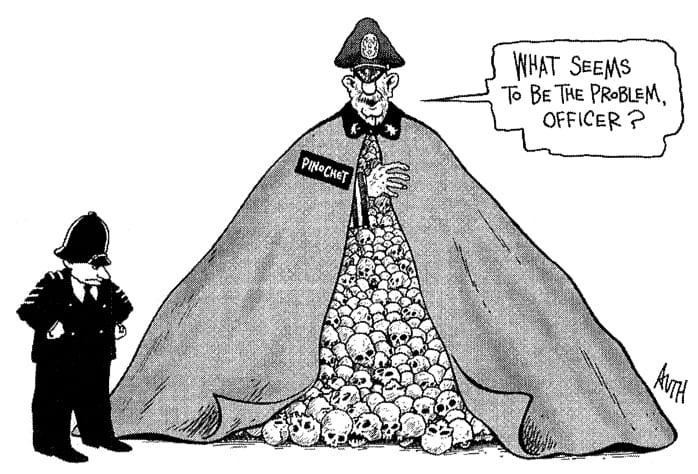

Just before midnight on Friday, October 16, 1998, police from Britain’s Scotland Yard entered a room in a small, private hospital in London and arrested former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet Ugarte. General Pinochet was recovering from back surgery, but the ramifications of his arrest would shake not only his world, but the way the entire world would come to view human rights prosecutions.

Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzón had issued a request for Pinochet’s extradition to stand trial in Spain for crimes committed in Chile during his brutal rule from 1973-1990. The legal basis of the claim was that the United Nations Convention Against Torture, ratified by a majority of the world’s governments, carried with it a “universal jurisdiction” that superseded the immunity formerly claimed by heads of state.

This was a tectonic shift and ushered in a new era of human rights prosecutions. David Sugarman, professor of law at Lancaster University in England, wrote on the 10th anniversary of Pinochet’s arrest:

This epoch-making decision – whose significance has lasted far beyond the return of Pinochet to Chile in March 1990 on grounds of ill-health, and consequent escape from prosecution – initiated a new stage in human-rights accountability. … The Pinochet case, and the universal jurisdiction that sustained it, turned the world upside down. It challenged the idea that important folk should be deemed ‘more equal than others’ before the law. … In Chile, while some advances in human-rights accountability were evident prior to Pinochet’s arrest, since 1998 the progress of human-rights trials has dramatically improved, … hundreds of officers have been charged and hundreds have been convicted for crimes committed during the period covered by the amnesty as a result of this interpretation. … Since the Pinochet case, domestic prosecutions against past leaders – for financial crimes as well as human-rights abuses – have increased markedly. In Uruguay, Surinam, Thailand, Peru and Bangladesh, for example, ex-heads of state or government are either in the dock or awaiting trial.

Although Augusto Pinochet died on December 10, 2006 in a Santiago military hospital having never been convicted of any of the multitude of crimes for which he was charged in various courts, Joan Garcés, former adviser to Chilean President Salvador Allende and now a human rights lawyer in Spain, said in a 2013 interview with Amnesty International: “We should not forget that Pinochet died as a fugitive from justice.

It was clear that international society saw him as a criminal.” Former Amnesty International Chile researcher Virginia Shoppeé continued in the same interview: “Pinochet did not come back to Chile as an innocent man – as a former president unfairly accused – but as a person guilty of human rights violations whose extradition had not been allowed for health reasons. The victims’ claims were again a public issue. Chile had changed. It was no more the Chile I had visited in March 1998, where nobody wanted to speak out about the military government’s crimes against humanity. Chile had to face the atrocities of its past – a past the country was denying until Pinochet was put under custody in London.”

Today, in this special section of The Tico Times, we commemorate the anniversary of that world-changing arrest with a series of articles. Norman Stockwell looks at the life of Frank Teruggi, a U.S. citizen killed in the days following the coup in 1973. Then, Joyce Horman, widow of murdered U.S. journalist and filmmaker Charles Horman, remembers the 40-year struggle to get answers to the many questions surrounding the deaths of Frank and her husband, Charles.

The 1982 film “Missing” chronicled her story. Next, a look at newly declassified evidence of U.S. government complicity as chronicled by Peter Kornbluh of the National Security Archive, an independent nongovernmental research institute and library located at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C. And finally, a chapter from his book “The Pinochet Affair,” where scholar and activist Roger Burbach recounts the arrest of General Pinochet that night in London.

A 41-year saga: Seeking the truth in the death of Frank Teruggi

By Norman Stockwell

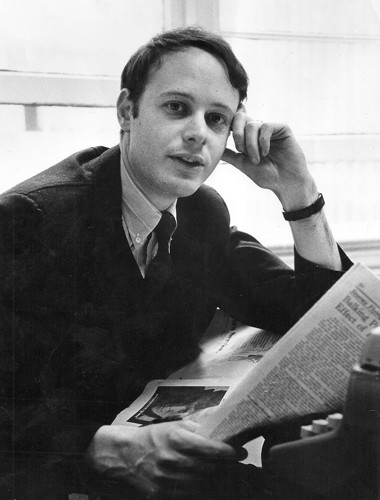

Frank Teruggi would have been 65 years old this year, a time when many in the United States start to think about retirement. But instead, Teruggi was brutally murdered by the Chilean military at the age of 24 in the days following the coup of September 11, 1973.

Forty-one years ago, a brutal military dictatorship took control of the nation of Chile after just three years of rule by the democratically elected popular president Dr. Salvador Allende Gossens. Allende’s election on September 4, 1970 was a thorn in the side of U.S. politicians. Henry Kissinger, then a national security adviser, famously declared in the months leading up to the election: “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its people. The issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves.” And then-President Richard Nixon, in recently released White House tapes, repeats more than once: “We’re going to give Allende the hook.”

After months of preparation, including a failed earlier coup attempt in June 1973 – referred to as the “Tanquetazo” or “Tancazo” – on the morning of September 11, troops moved in and took control of La Moneda Presidential Palace, where President Allende died of a gunshot wound in his office. Gen. Augusto Pinochet Ugarte was installed as dictator of Chile for the next 17 years. In October 1998, Pinochet was placed under house arrest in London based on charges of human rights violations, but he died in December 2006, never having been convicted of the crimes of which he was accused.

The Chilean government today officially estimates 3,095 people were killed during the coup and its repressive aftermath, and currently some 700 former military officials face trial, while 70 have been imprisoned in connection with their role in crimes against humanity. U.S. government support of the coup is now widely acknowledged, being first documented in hearings led by Senator Frank Church (D-Idaho) in 1976, and later confirmed in a September 2000 U.S. Intelligence Community report which said the CIA “actively supported the military Junta after the overthrow of Allende.”

Among the thousands of Chileans and other internationalists who died were two U.S. citizens: Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi. The story of Charles Horman’s disappearance and death, and his family’s search for answers received national attention through the award-winning Hollywood film by renowned director Costa-Gavras and starring Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek. Frank Teruggi’s story has received less public attention, but his life and work deserve to be remembered.

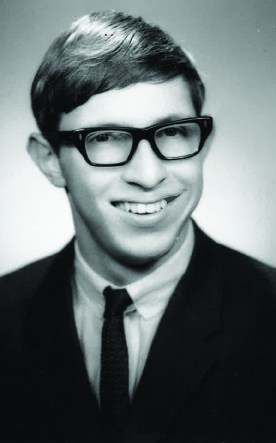

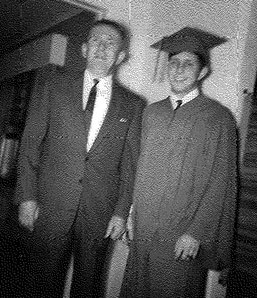

Born on March 14, 1949, Frank Randall Teruggi, called “Randy” by his family since his father was also named Frank, was the first of three children of two second-generation immigrants from Italy and Slovenia – Frank and Johanna, known as “Jennie.”

“Our family was a working class household. My mother never finished education beyond eighth grade. She came from a really poor coalmining town in Pennsylvania. My father came from an equally [poor], company coalmining town in southern Illinois,” said Janis Teruggi Page, Frank’s younger sister, now a senior professorial lecturer at American University, in Washington, D.C.

A young Frank developed a strong sense of social justice from his family, and a keen interest in the world around him. “I think, although they weren’t very political at all, I just think their sensibility sort of came out, sort of leaked out, as far as their care for the underdog and sense of ethics,” Janis said. For the young Teruggis – Frank, Janis and younger brother John – learning and knowledge were very important in the home as well as at school.

“We were a very literate household, even though my mother hadn’t attended high school. There were always four newspapers in the house – my father would come home from work – he was a typesetter, a member of the Typesetter’s Union, and very proud of it – he would come home from his commute back from downtown Chicago to suburban Des Plaines and read the newspaper for most of the evening,” Janis recalled.

Frank Jr. grew up in a typical U.S. suburban household of the 1950s and early ’60s, but from a young age he was very thoughtful. “It was a typical childhood. I mean he was involved with the Scouts. I guess today you’d call him a nerd. But he had an extremely high intellect. Really advanced for his age, and [he] found more reward, I guess, not with active sports but more intellectual activities,” she said. It was his early exposure to liberation theology in high school at Notre Dame Academy that first sparked his interest in Latin America. Janis remembers “from conversations with him, very old memories of conversations with him, [the transformation came] after he decided to specialize in Spanish and to not only study the language, but study the culture and the history and the politics. … I think that was the beginning of his interest in South America.”

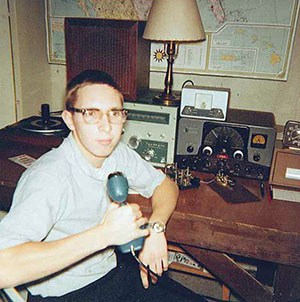

In 1967, Frank received a scholarship to the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. There he continued his interest in ham radio and studied social sciences. Today, Caltech offers an annual award that honors the spirit of Frank’s life, especially “in the areas of Latin American Studies, radical politics, creative radio programming, and other activities aimed at improving the living conditions of the less fortunate.”

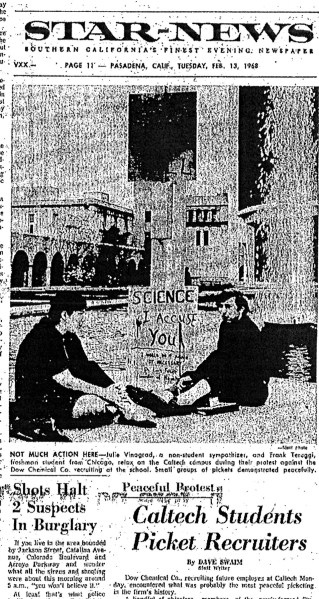

He also became involved in the growing opposition to U.S. involvement in the war in Vietnam, founding the first Students for a Democratic Society chapter on campus. A February 13, 1968 article in the Pasadena Star-News shows Frank as a freshman picketing the Dow Chemical recruiters that had come to campus. Similar protests against Dow and their role in the production of Napalm were being held on campuses across the country, including a famous one in Madison, Wisconsin, that was brutally repressed by the police.

When summer vacation came in 1968, he returned home to Des Plaines, Illinois, and began working with Chicago Area Draft Resistors, or CADRE. He participated in a large peace march on Hiroshima Day that August with a group of students, professors and clergy members costumed as victims of war, and later that month, he participated in demonstrations outside the Democratic National Convention. Shortly after the convention, he participated in a guerrilla theater performance at a north suburban art fair calling attention to police brutality in the suppression of the protests at the convention. Frank and another actor were arrested for disturbing the peace, although apparently no record of this arrest was found when the FBI checked Frank’s file with the Chicago Police in December 1972.

Shepherd Bliss was a seminary student at University of Chicago Divinity School. He remembers working with Frank: “My relationship to Frank started in Chicago. We worked in a group called the Rapid Transit Guerrilla Communications, which was a street theater group, and we did a lot of work on the subway. [It was] basically anti-war work. And we were very active with the Nixon counter-inauguration and the 1968 National Democratic Convention – Frank and I and the whole group.”

In the fall, Frank went back to college, this time at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Later he transferred to UC-Berkeley. Janis Teruggi, who later became a student at Berkeley at the time of Frank’s death, visited him there once in 1969 or 1970.

“I can remember a passion of his was the amateur radio hobby that he developed quite young, where he would develop relationships with people as best he could [and] play chess with them, across the world,” she said. “And he continued that interest in radio. I remember when I visited him he was living in a communal house in Berkeley, and down in his basement, he had a radio receiver where he was monitoring police calls in Berkeley. So a team of citizens [could be organized to] arrive on the scene if they learned that a free speech action was being challenged by the police. I don’t know if they actually did that, but that was [how] he was using radio at Berkeley.”

In late 1970, Frank moved back to Chicago and got a job with Postal Service. He moved into an apartment in the south-central, largely immigrant neighborhood of Pilsen. His sister remembers a poster of Chinese leader Mao Zedong was displayed on the wall. Frank also found a home with the Industrial Workers of the World, a radical labor union that said “all workers should be united as a social class to supplant capitalism and wage labor with industrial democracy.”

He frequented the New World Resource Center, a bookstore and meeting space founded by members of the Committee of Returned Volunteers, or CRV. According to FBI records, Frank attended a CRV meeting in Allenspark, Colorado, as a delegate in August 1971. NWRC remained a major resource center for books, literature, films and speakers on liberation movements and anti-imperialist struggles for nearly four decades.

A colleague who calls himself “Burny” recalled their meeting: “He and I met initially because he was working with a group called CAGLA, Chicago Area Group on Latin America, which was a solidarity organization that was doing work around various countries in Latin America, including Cuba, but also various South and Central American countries. And they had a relationship with another organization called the Committee of Returned Volunteers, which was an organization of people like returned Peace Corps Volunteers and people who had gone to other countries as part of various volunteer efforts, and … people who generally developed the anti-imperialist kind of perspective.”

Burny and Frank also contributed to the Chicago Seed, an alternative newspaper founded in 1967.

“I started working with the Seed, and Frank would come around and give us information about various topics – especially about Latin America – and he was always interested in getting us to print some [of this] material. Sometimes he’d write stuff himself; other times he’d feed us some information or try to get somebody on the staff interested in one or another of the topics. I would characterize him as reliable and very, very honest and principled. He was committed to a variety of what he viewed as just causes, and, you know, he was willing to put himself on the line a lot of times in terms of devoting his time and energy,” Burny recalled.

“One word I would really characterize him with is ‘reliable.’ He was the kind of person who you could ask him to try and do something and he would come through – he wouldn’t let you down. People on the Seed would sometimes ask him for some particular information about some Latin American country, and if he didn’t have the information, he would go out of his way. He would research it. He’d talk to other people. He’d read stuff and he’d get back to you. It wasn’t an idle thing. … He would make the point of getting you the information that you needed.”

But Frank’s goal was to raise funds to travel to Chile and study political economy at the University of Chile. Shepherd Bliss remembers: “He was living in Berkeley at the time, actually, [when] I went to Berkeley to recruit him to work with us. We had a group called CAGLA, the Chicago Area Group on Latin America. When I decided to go to Chile, I met with [Frank’s family], and, I committed myself to his family, because Frank was a very nonviolent activist, a theater person, artist, young, enthusiastic, so I committed myself to his family to sort of look after him. I wasn’t a lot older than he was, but I was a little bit older.”

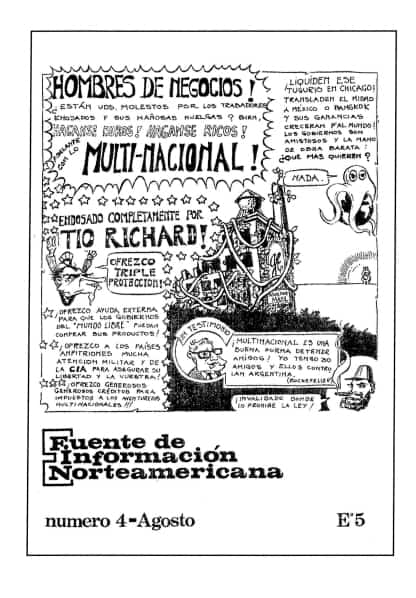

When Frank arrived in Chile in January 1972, he rapidly connected with a group of U.S. activists that had formed FIN, which stood for “Fuente de Información Norteamericana,” in Spanish. FIN members described their project 40 years later in the program book of the Charles Horman Truth Foundation’s Tribute to Justice dinner as “a small group of progressive young North Americans drawn to Chile to witness, study and live el proceso chileno. We created FIN to inform Chileans about how the U.S. government and corporations were using their power to suppress popular movements in Chile and around the world,” the program stated.

Steven Volk was studying for a doctorate in history at Columbia University in New York when Salvador Allende was elected. He now teaches Latin American history and museum studies at Oberlin College. Volk first met Frank through FIN.

“We would often meet in the evenings to discuss putting together what turned out to be these newsletters that we composed,” Volk said. “What we were trying to do, what we were looking for in some way, was a method of expressing solidarity with the broad movement toward socialism and anti-imperialism that was embodied within the popular unity government of Chile and Salvador Allende. And what we came upon as the most comfortable of mechanisms was not for us to analyze the Chilean situation itself, which was done much better by Chilean sources, but rather to talk about what was happening in terms of progressive movements in the United States.

And those included labor movements, anti-imperialist movements, movements against the war in Vietnam, movements within the black community – things of that nature. And so we would decide on a series of articles that were usually taken from the progressive press, or sometimes from the mainstream press in the United States. … We would get together to decide which would be good ones to translate and then bring to a Chilean public.”

Mishy Lesser, who is now learning director at the Coexist Learning Project, recalled being the youngest member of FIN: “This whole crowd of Americans who were there, most of them were graduate students, and I was kind of the runt of the litter. I was a secondyear undergrad at a Quaker college that created an opportunity for fostering global citizens and for people like me who were very drawn to experiential learning. I chose to go to Latin America after my first year at Friends World College, because for me the burning question at that time was, ‘Why do so many people in the world hate my country?’”

Lesser said the process at FIN was very collaborative: “We created FIN in the living room where I lived. There were three of us sharing space at that point; we were very much in the spirit of a collective. So, there were meetings, and work was divided up and decisions were made on what articles to focus on and what information to try to make available, and what translations to do.

It wasn’t hierarchical; it was tremendously collaborative and people were able to sort of play to their strengths. Some people were about to make arrangements for printing and for distribution in the kiosks of Santiago, and other people were able to get … the information that we thought was important to make available to a Chilean progressive community seeking social justice for their country.”

This was before the Internet, and Lesser noted that “it was not easy. Making it available in Spanish, in good Chilean Spanish, was another challenge. There were many, many tasks, and we eventually needed to get an office where we were able to have meetings and do work. And it had the luxury of a telephone – most of us didn’t have phone in our homes then.”

It was Lesser who first discovered their phone was tapped.

“I was in the FIN office. There were others there. I don’t recall if I was there for a meeting. Sometimes I would go there because I needed to use the phone. … I was making a call somewhere to see if there was going to be an afternoon meeting that I was supposed to attend, and I dialed the number of the place, and rather than the people who were supposed to answer picking it up, what I heard on the other end of the line was [a voice saying], ‘U.S. Embassy.’

The tapping was so primitive in those days, and FIN’s office was geographically not that far from the U.S. Embassy. … Somehow, the wires got crossed. And I knew the voice of the receptionist at the U.S. Embassy, because when I first arrived in Santiago, I used to get my mail, … I used to get letters from my family at the embassy’s general postal address.”

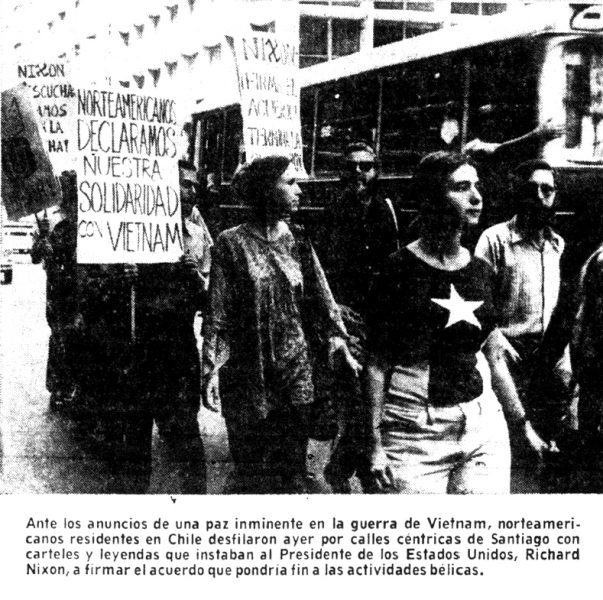

Frank continued his anti-war activity while in Chile, as well. He appears next to Mishy Lesser in a January 21, 1973 photo in El Mercurio, the Chilean national newspaper that was later shown to have been receiving covert U.S. funding to act as a promoter of the coup. On the day after Nixon’s second inauguration, Frank and other U.S. activists marched in Santiago to call for the U.S. to go along with peace accords in Paris with the North Vietnamese to bring an end to the war. Frank was a prolific writer during this time, sending reports back to family and various leftist publications. Burny recalled how detailed the letters were: “He did write to us at The Seed, to me in particular, but also things just addressed to the staff of the paper in general. Frankly, some of the letters … were detailed enough, very interesting stuff, but very detailed to the extent that unfortunately they weren’t really suitable for us to print, because you had to have a lot of background. … He was talking a lot about the relationship of the different forces, the different local political parties and so on, and in terms of a general circulation underground paper they were a little bit too advanced.”

Janis remembers watching how Frank’s analysis developed: “I have about 35 letters from Frank that he wrote almost every week or two, that really revealed his transformation from a sort of impulsive radical to one [who was] much more thoughtful, understanding the theoretical basis for economic change.”

Steve Volk became great friends with Frank. “He was a really nice guy. I mean he was very genial, he always joked a lot, had a lot of good humor, [and] worked hard,” Volk said. He “never shirked the kinds of things that he had to do. At the same time he was perfectly committed to seeing this process through. And, at times it led him into places that proved to be quite dangerous, including … there was the other [attempted coup]. … This was called the “Tancazo,” on June 29, 1973, in which one brigade of the army launched a sort of presumptive coup and was quickly put down. [Frank] went to the center of the city and ended up being lightly grazed by a bullet in his foot. I think most of us stayed away from that. He kind of was drawn to seeing in particular, and in person, what was going on and that gives some sense of who he was.”

When the coup happened, anyone who had been involved in supporting Allende’s administration was a potential target for arrest. Said Volk: “We were, all of us, I believe, sort of operating within the framework of laws that existed up until September 11, 1973, at which point everything changed. … In the immediate days after the coup there was a curfew, we couldn’t go outside. Not everybody had a phone. I didn’t have a phone, for example. But in the days in which we finally could sort of regain contact with people in FIN, we began to set up a simple system of trying to check in with each other to make sure that we were OK. …

“I learned from Joyce Horman that her husband had been disappeared at that point. We basically established this network in which one person [in FIN] would call another person, and they would call a third person, and if there was no answer on the phone then we would call back after curfew lifted in the morning. If there was still no answer, we would report a disappearance to the U.S. Embassy.

And so we had a kind of process for keeping in touch with each other. That’s one method whereby we learned of the arrest of both Frank and David, and then I learned more about it when David came by my apartment shortly after he was released from the National Stadium, and he had told me that he and Frank had been arrested by soldiers who took them to the stadium, which was a large holding place for prisoners. They spent the night there, sort of huddled together, and at one point, Frank had been called away for interrogation. He didn’t return, and David didn’t see him again.”

Mishy Lesser remembered that day of the coup: “It was my first glimpse of how terror overtakes people, because people were swarming; … there were just two little grocery stores on our street and people who had been through political unrest before – unlike me, [who was] born in New York City. I watched as everybody was trembling, … and there was a frenzy to try to grab food, because everybody but me knew what was coming, which was a curfew and military raids, and you wouldn’t be able to go out on the street.”

Adam Schesch, another U.S. activist who was living and studying in Chile at the time, recalled: “We were actually seized on the third day, on the afternoon of the 14th. … We heard the campaign on the radio and neighbors talking about the campaign against foreigners, and I made a call to the embassy, and the embassy official, whoever it was that answered the phone, said, ‘No, there is no danger.’ They had no plans, they knew nothing about anyone getting hurt, and there was no violence, and so on. I mean, as far as they were concerned, the whole thing was a Sunday picnic. And there were other people who … attempted to call the embassy to find out, … in particular people who felt threatened, what the embassy would do to protect them. And I know for a fact that there were Americans who ended up fleeing to other embassies that were more sympathetic.”

Lesser went out of the central city to seek safety, and then, “about seven or 10 days after the coup, I was able to make a phone call. And I called Jill Hamburg. She was the only one of us who had a phone. She was so glad to hear from me because they hadn’t heard from me. So they thought that I had been arrested as well. They were very worried. And she told me that Frank and Charlie and Davy had disappeared, that they’d been taken. And that’s how I found out about it.”

Evidence gathered by the National Security Archive and published by Peter Kornbluh in his comprehensive volume “The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability” now confirms that Frank and his roommate, David Hathaway, another FIN member, were taken from their home at 9 p.m. on September 20, questioned at a nearby Carabineros station and delivered to the National Stadium, which had become a holding tank, torture chamber and execution site for thousands of activists and others simply caught up in the frenzy of coup. The world-renowned activist-musician Víctor Jara was killed in another nearby basketball stadium on September 15. In his last poem, smuggled out of the stadium, he wrote:

There are five thousand of us here

in this small part of the city.

We are five thousand.

I wonder how many we are in all

in the cities and in the whole country?

Adam Schesch and his wife at the time, Patricia Garrett, were denounced by neighbors as part of a campaign promoted on the radio to target foreigners as pro-communist. They spent close to 10 days in the stadium. “We were denounced by people in our neighborhood. They had obviously figured out that we were sympathetic to the popular unity or pro-Popular Unity. … When we were seized and put in the National Stadium, we did not know that they [Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi] were even there. Now, I did get into a room with almost 150 foreigners. I got into a holding room where there were several Jesuit priests and Protestant ministers and Americans who were working autonomously, independently with different government agencies, teaching at some of the universities in Santiago,” Schesch said. “So, there were a lot of Americans who were considered progressive or dangerous by the Junta. They were rounded up, along with a whole pile of other foreigners. There was a campaign to denounce foreigners in Chile.”

Schesch has testified publicly many times about what he saw in the stadium, and the memory is still very strong for him. “It was a horror show,” he said. “I’ve said to people the only thing that I, in my whole life, could compare it to was horror movies from Hollywood about Dante’s inferno. It was a hellhole. The soldiers were on drugs to be kept awake, and … there was an insanity to the whole thing. There was a gross brutality.”

Chilean journalist Pascale Bonnefoy Miralles, who has covered the Teruggi case for a number of years, quoted in her book “Terrorismo de Estadio” from the affidavit of a Belgian named André Van Lancker, also tortured in the stadium. He was told by other detainees that they had witnessed Frank during an interrogation in the stadium. They saw him beaten and tortured with electric shocks, then killed by a machine gun. The torturers had gone “too far” and were afraid of having problems with the U.S. government, so they kept Frank’s name off the lists of prisoners. His body was later left in a public street, where it was discovered the following day, September 21, just after 9 p.m. It was brought to the morgue.

The Teruggi family spent days not knowing what had happened to Frank. Steve Brown, who covered the story extensively for the Daily Herald suburban newspapers in Chicago, remembered interviewing Frank Teruggi Sr.: “My recollection is that [the Teruggis were] very disappointed that there wasn’t more attention, more resources paid to this situation, because there were … a number of Americans besides these two, as I recall, who were for a time missing because of the chaos in Chile. And I think [Frank’s father] was just disappointed that a government he respected, … that there wasn’t more attention being given to this thing. And I remember him having some conversations, trying to have conversations getting political figures involved.”

It was Steve Volk who eventually identified Frank’s body at the morgue.

“David [Hathaway, Frank’s roommate] was released the next day [September 26, according to U.S. Embassy records] from the National Stadium and given 24 hours to leave the country, to pack up his things and leave,” Volk said. “He also was taken to the morgue to see whether Frank was there, and as he reported to me he was in no shape to really identify anyone, and he asked me whether I would go to the morgue and see if Frank’s body was there, because nobody knew at that time where he was. So, as soon as I talked to David, I went to the U.S. Consulate’s office and tried to talk to the consul, Frederick Purdy. A messenger sort of went from the front of the office where I was standing to the back where Purdy had his office, and I heard him shout through his door, ‘I don’t give a damn what Volk wants, he’s not going to the morgue.’

And then the guy came back and said, ‘No, we can’t arrange this for you.’ What I was looking for was basically a salvoconducto, a sort of safe conduct that would mean I wouldn’t have any trouble if I went to the morgue as an individual citizen. So, I went back to my apartment, and by the time I got to my apartment there was a note slipped under the door from James Anderson, who was one of the members of the consulate, who said that they would pick me up the next morning and take me to the morgue. They did that, and it was at that point, and after about maybe 20 to 30, 35 minutes of looking at the bodies that were there that I discovered Frank’s body.”

A confidential diplomatic cable, released by WikiLeaks, sent on September 26 at 3 p.m. from the U.S. Embassy in Santiago to the Secretary of State in Washington, D.C., and signed by then-Ambassador Nathaniel Davis, requested contact information for Frank’s next-of-kin and stated that the “body must be taken out of Chile in 48 hours.”

The family was finally notified on October 3, but the body was not shipped home until about two weeks later. Additionally, as a report in the Des Plaines Herald revealed, the family was billed $850 in shipping fees to get Frank’s body back, and those fees had to be paid in advance.

Frank Randall Teruggi was buried in a cemetery in Des Plaines, Illinois. Frank’s sister, Janis, recalled that she “and his closest friends each placed a red rose on his casket. There were large bouquets of red roses at his wake and funeral. Afterwards, my parents took them to the Carmelite Monastery in Des Plaines and the nuns dried the petals and made a rosary from them, which I now have.”

According to newspaper reports at the time, over 100 friends and family members attended, and the late exiled South African activist poet Dennis Brutus wrote this poem on the occasion:

FOR FRANK TERUGGI

(Killed in Chile, Buried in Chicago)

A simple rose

a single candle

a black coffin

a few mourners

weeping;

for the unsung brave

who sing in the dark

who defy the colonels

and who know

a new world stirs.

The poem was published in “UFAHAMU: A Journal of African Studies,” Vol. 4, Issue 2, 1973.

News of Frank’s death saddened and still remains painful to all who knew him and worked with him. Burny, of the Chicago Seed, recalled: “We all heard about the coup, there were demonstrations here around that. Obviously the letters from Frank stopped coming, and it wasn’t until quite a while later that we wound up finding out that he’d been killed, and all the details of that didn’t really come out for a while. … That was really a shocking thing to realize what had happened to him. And, you know, everyone at the New World Resource Center really loved him a lot, and the people on the Seed staff, a lot of them knew him too. And it was … really something that saddened a lot of people very much.”

Frank Teruggi Sr. spent years seeking answers. Reporter Steve Brown remembered: “You know, he just wanted to find his kid. He just wanted to see what could be done, and then when it was, … when the body was found, he was very frustrated there wasn’t much information. But I think Mr. Teruggi had faith in the government and trust in the government, .and the frustration that not more could be found. I think the government was putting more burden on the situation with Chilean officials in terms of why they couldn’t get information.”

Frank Teruggi Sr. joined a delegation that traveled to Chile from February 16-23, 1974. The group was called the Chicago Commission of Inquiry Into the Status of Human Rights in Chile. It included UE Vice President Ernie DeMaio, Chicago Alderwoman Anna Langford, and Rev. James Reed, as well as Joanne Fox Przeworski, who recently had worked as a doctoral student in Chile. They visited the embassy, where according to Fox-Przeworski, “it was a whitewash kind of a meeting, explaining that the embassy couldn’t really do anything for us, that they were trying by all means to help the Teruggi family, etc. It was the usual kind of cover-up because we later learned that they did know much more than they were telling us.”

The commission’s report was excerpted and printed in the New York Review of Books on May 30, 1974. Point 11 in the “Summary of Findings” states, “The Embassy of the United States seems to have made no serious efforts to protect the American citizens present in Chile during and after the military takeover.”

During the trip, Frank Teruggi, Sr. met with then-Ambassador David Popper, who had been assigned to Chile after the coup. A declassified report of their February 18 conversation includes an exchange where Frank Teruggi Sr. says to Ambassador Popper, “It is difficult for [my] family to understand how the USG can be helping the Government of Chile when they don’t even answer our questions.”

Said Steve Brown: “When Frank went missing and all that, I think the embassy and the State Department were trying to put all the blame on the Chilean officials and the uprising and the government. And then, … when the trip was held, they came back frustrated and sensing that, rather than there being a lack of information, the U.S. government didn’t really care about the whole thing. It wasn’t a high priority in their work.”

Joanne Fox Pzreworski called Frank Teruggi Sr. “a very gentle, persistent, extremely kind man who was literally baffled by [the thought that] his own government could have been implicated in the death of his son, an American. Frank [Sr.] had served in the [U.S. Army] during World War II, so he had a patriotic view of what the government does on behalf of what it perceives as its own interests. So this was a real eye-opener for him, and a major, major – not even disappointment, a disillusionment.”

Janis Teruggi, too, noted her father’s disappointment: “I can remember just a complete dejection and sadness when he returned. … Afterwards he just took to a long, long period of letter writing. That was his tool. That was the way he felt was the appropriate way to seek justice.”

A State Department document dated April 1, 2000 states that, “Though the Teruggi case received less press coverage than the Horman case, the family has also sought a full accounting of the circumstances leading to Frank Teruggi’s death. Frank Teruggi, Senior traveled to Chile to try to discover the facts. He never learned those facts and remained bitter until his death in 1995 about the murder of his son by Chilean security forces and a perceived lack of USG assistance with the case.”

It would be years before any new information would come out. Then, during the administration of U.S. President Bill Clinton and following in the wake of Pinochet’s 1998 arrest in London, beginning on February 13, 2000, a huge number of documents were made public, including some memos that may lead to an understanding of why Frank was targeted. Peter Kornbluh of the National Security Archive explained that Pinochet “was arrested at a time that we had a set of officials in office in Washington under Bill Clinton who had opposed the coup when they were younger, who stood for human rights and who saw the opportunity to do a major declassification of secret documents, among them operational CIA documents about the coup and about Pinochet’s repression. And some 23,000 new documents were declassified by a Special Presidential Discretionary Release over an 18-month period after Pinochet’s arrest. We pushed for those documents to be released.”

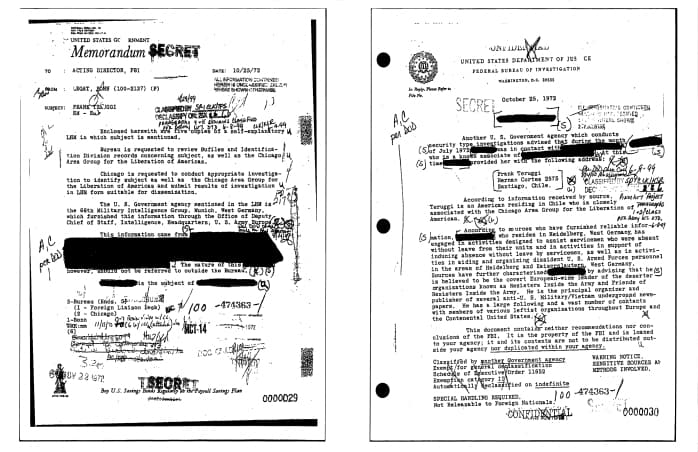

Most damning of these is an FBI memo dated October 25, 1972, 11 months before Frank’s arrest. The memo listed Frank Teruggi’s street address in Santiago. If this document had been shared with Chilean security forces, it certainly would have made him easy to locate. The document suggested that Frank was corresponding with a GI resister in Germany who was also being watched by the FBI, as Kornbluh explained: “The FBI kind of stumbled onto Frank Teruggi in kind of an odd way. … The FBI and the CIA were monitoring the anti-Vietnam War protesters and activists in Germany who were kind of pushing for U.S. servicemen to go AWOL from their base in [Heidelberg] Germany, and to come out publicly against the war.

They were monitoring a particular individual in Munich, and he got a letter from Frank Teruggi when Frank was in Chicago and working with an antiwar coalition there. And the FBI started to track Teruggi, and opened a file on him in which they labeled him a subversive in 1972. And, actually, one of the FBI documents had his address in Chile where he had recently moved, and the address where he was actually living when he was arrested over a year later. The judge seemed to feel that these documents were reflective of efforts by the U.S. government to keep track of … Teruggi.”

Steve Volk is less certain of the reason for Frank’s arrest. “The case of Frank also poses many questions,” Volk said. “Very recent information suggests that he, too, could have been picked up on the basis of information, … this very bizarre information that was collected by the FBI that suggested he was involved in aiding soldiers that were trying to escape the Vietnam War by deserting the army in Germany. And there’s one document in his file, a bit redacted, but which does seem to point to the fact that he was involved in this process of helping deserters. When I read that, … it was the first I ever heard of that. It seemed somewhat disconnected from anything else, and I’ve never been able to really find any backed-up information on that. But there was a possibility that he was picked up for that reason.”

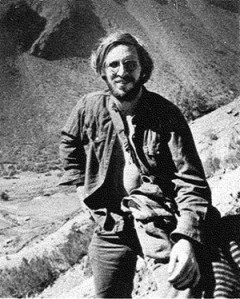

Roger Burbach, now director of the Center for the Study of the Americas, was in Chile then working on his doctoral dissertation. Burbach had worked with Frank in Chicago in 1971 organizing an Anti-Imperialist Conference held there. They would meet again in Santiago, both working with FIN. Burbach thinks that the bullet wound Frank received during the Tancazo protest may have played a part as well.

“The bullet wound he had suffered back in June was probably incriminating, amplifying his dossier with the agency,” Burbach wrote in a forthcoming autobiography, referring to the CIA, which was known to keep tabs on all U.S. activists in Chile.

Since the release of the documents pertaining to Teruggi and Charles Horman, new court cases were filed to try and obtain answers. Peter Kornbluh of the National Security Archive said that, “In December of 2000, the widow of Charles Horman, who was a journalist living in Chile with his wife Joyce, went to Chile and filed a court case, asking judges to officially investigate who had killed him and why. His case has been immortalized along with the other U.S. citizen Frank Teruggi in the movie ‘Missing,’ and, 14 years later, we finally have a ruling in this case.

Three years ago, Judge Jorge Zepeda, a Chilean special investigative judge, indicted three people – one was a U.S. Naval Captain, Ray Davis, and the other two were Chilean intelligence officers Rafael González and Brigadier General [Pedro] Espinoza – for the deaths of these two Americans. An investigation continued, and just last week [on June 30, 2014] he now says in a conviction that the case will go forward. Captain Davis has died in the interim, and these two intelligence agents will be essentially convicted. They now have the opportunity to appeal, but this is a major step forward in this long saga. It’s a 40-year saga since they were killed, and a 14-year saga of legal efforts to find out who killed them and why.”

The judge’s ruling stated that the murders of Horman and Teruggi were part of “a secret United States information-gathering operation carried out by the U.S. Milgroup in Chile on the political activities of American citizens in the United States and in Chile.” Sergio Corvalán, a human rights lawyer working for the Horman and Teruggi families on the case, told New York Times journalist Pascale Bonnefoy that he felt the ruling confirmed what the families had long believed: The Chilean military would not have acted against the victims on their own. They must have received approval from U.S. officials.

Janis Teruggi Page is glad to see the decision, but she is uncertain of the next steps. “Joyce [Horman] and I are both waiting to get a clear understanding of the evidence against the United States government,” Janis said. “We have faith in the long judicial process, the long investigative process, and the support of our lawyers that resulted in the indictment the Chilean court approved for the criminal case. We have faith that it is grounded on good evidence, but we don’t know what that evidence is, and depending on what we learn, there may be more legs for this lawsuit.”

Peter Kornbluh said, “The judge in the case now is saying that he has evidence that such information [about Horman and Teruggi] was [received] from the Americans, … not the CIA, but an American Naval intelligence unit led by Captain Davis. And that this information was used by Chilean intelligence not only to arrest Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi, but basically to decide that they were subversive leftists who deserved to be executed at the National Stadium. I should say that we haven’t seen the evidence that links the Americans, Ray Davis and others, to the Chileans who undertook these executions, but the judge’s ruling strongly implies that he has such information, and on that basis is convicting these officials. But, we have to wait until the judge makes his documentation, his affidavits, any Chilean records that he’s got, available in court before we can advance our historical knowledge of what really happened in this case.”

When contacted for this article, Judge Zepeda’s office declined comment because the case is ongoing.

After 41 years, it is not clear what resolution is possible, but many hope for the full story to come out. Steven Volk noted that the issue “that, of course, burns at all of us who cared about these two people and cared about the events is that they were – there is just absolutely no doubt – both of them were murdered. … And we want the truth. There are people who do know the truth, and this has not been forthcoming for over four decades. It’s always been our hope that someday we’ll be able to find out this answer definitively. It won’t bring either of them back, but it does suggest ways, … lessons that we need to learn about both how the United States operates in the world … and how other countries operate in the world. And this is information that we should have had decades ago, and we hope that someday we’ll get.”

Peter Kornbluh noted that, “Nobody’s been ever sent to jail for the murder of these two Americans, … and almost nobody’s been sent to jail, if I know the Chilean cases correctly, for almost any of the executions of probably 300-350 people in the National Stadium in the days following the coup. Murders by execution – which were carefully planned, with people carefully identified and carefully vetted in the days after the Chilean coup, all of this at the time when the U.S. is actively embracing Pinochet – those executions have really never been fully aired, and the people that committed them held fully accountable.”

Frank’s friend Burny said he “wants to see the truth of what happened established. I want to see some of the blame put on the people who were actually involved. You know, the fact that these people are still walking around and are honored, … speaking at universities, regarded as elder statesmen and so on. The truth of the matter is real justice is not going to ever be done on this. But at the very least the truth of what happened should somehow be officially acknowledged. It’s not like people like Henry Kissinger are going to be thrown in jail. It’s not going to happen.”

Mishy Lesser hopes for “a government in our country that is courageous enough to accept responsibility and be accountable for all of the atrocities, including this, that we have committed, in the name of protecting our freedoms and our country and our way of life. … I would hope that someday there would be an enlightened group of leaders who would actually not pretend that we didn’t do it. … Maybe there will be justice in Chile with the Chileans who were involved with the murders. You know, would I love Henry Kissinger to be on trial? Yes, I would love it if Henry Kissinger could be tried. Maybe that’s the short answer to your question.”

Norman Stockwell is a freelance journalist based in Madison, Wisconsin, and serves as operations coordinator at WORT-FM Community Radio. His 1998 article on Madisonians who experienced the coup in Chile can be found here. In 1970-71, he lived in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood, a few blocks from Frank Teruggi. They did not know each other. A shorter version of this article previously appeared at Progressive.org.

Missing Charlie

By Joyce Horman

Forty years ago in Santiago, Chile, my dear, smart, Harvard-educated, independent thinking, loving, trying to figure it all out and do the right thing journalist/documentary filmmaker husband was stolen from my life, from the lives of his loving parents, and all of his friends. Charles has been described as “an American sacrifice” – one of the many victims of the U.S.-backed coup in Chile on September 11, 1973. The presence, voice, thoughts, and future life of Charles Horman and thousands of others were nonfactors in the calculations of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger to bring down the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende.

We loved Charles so very much but even more importantly, we knew he would contribute to the good of the world’s future, just as countless Chileans tortured and killed by Augusto Pinochet’s murderous squads would have enriched the world had they lived.

In one of the last conversations I had with my beloved husband, we decided that we wanted to go back to New York together and start a family. Nixon, Kissinger and Pinochet deprived us of that, too, just as they snuffed out the hopes and dreams of their Chilean victims.

Forty years is a long time to wait for even a modicum of justice, but I’ve endured the decades thanks to some wonderfully courageous people.

Thank you, Ed Horman, for flying into the middle of a military coup d’état in Chile to search for your only son, and thank you for teaching me to press for answers.

Thank you, Elizabeth Horman, for letting Ed go to Chile, knowing the risks.

Thank you, Terry Simon, who had been with Charles in Viña del Mar on the day of the coup, for braving two weeks looking for Charles with me, and for pursuing the only people who might be able to find and save Charles: the American officials whom you had met in Viña. And thank you for standing by the search for truth for so many years.

Thank you, Steve Volk, for going to the morgue in Santiago to look for Charles and our friend and fellow American citizen Frank Teruggi, so I didn’t have to, and for telling the story over the years in ways that students understand.

Thank you, Thomas Hauser, for writing “The Execution of Charles Horman: An American Sacrifice,” which included the words of American military personnel who had met Charles in Chile.

Thank you, producers Eddie and Millie Lewis, for speaking to us about doing a movie based on Hauser’s book.

Thank you, Costa-Gavras, for making that powerful movie “Missing,” which opened the minds of so many Americans to their government’s wrongdoing and wrong thinking.

Thank you, Jack Lemmon, for so brilliantly playing Edmund Horman.

Thank you, Sissy Spacek, for capturing the hearts of Americans for Charles’ story.

After we returned from Chile, Ed pushed Terry and me to write a diary of what had happened. This was extremely difficult for me. Ed insisted. He led the family to testify before Congress. I also found that difficult, because from my own personal darkness, I perceived a government not representing my family or me. I was speechless in my sorrow, so all I could do, really, was simply be there.

In 1977, Ed started working with the Center for Constitutional Rights to file a lawsuit against the U.S. State Department for information regarding Charles’ wrongful death. That was also difficult for me, especially at first, because it seemed so unlikely that Kissinger and his team would tell any of the truth. I remained deeply depressed over the loss of my husband, but the legal team was so supportive that it enabled me to be present, though I felt I contributed very little.

Three years later, when “Missing” was in the works, I had low expectations again. I doubted Hollywood’s ability to handle the material in a dignified way, but Ed had such confidence that it would be all right. I did ask the scriptwriter to change my first name (in the movie it is “Beth”) so if my skepticism proved correct, I could duck my association with the film. When we all went to Mexico to watch the last week of filming, we experienced the utter excitement of Costa-Gavras and the whole cast and crew about the movie. A glimmer of hope entered my heart. In the spring of 1982, I went with Ed and Elizabeth and Terry to the Cannes Film Festival, where “Missing” premiered. I saw the impact the movie had on its audiences. It was more effective in conveying our story than I could have ever imagined.

People began to ask if the unbelievable scenes in the movie were true. I accompanied Ed on speaking tours to universities to discuss the accuracy of the movie. He was a wonderful speaker, and after a few outings with him, I ventured to speak to a few audiences on my own. That, too, was difficult for me; I have to confess that I was frightened of public speaking. But my father-in-law demonstrated to me that it was important to do, so I tried.

A few years later, Ed no longer could accept invitations to speak, but I could and did. I always found that the questions from students who saw the movie, even though they weren’t around or at least not aware in 1973, indicated an understanding of what had happened. For its audiences, this film facilitated a new awareness of the immoral actions and gross deceptions of the Nixon-Kissinger Administration and provoked extensive debate over the values that the United States stood for as a nation.

Ed did not live to see General Pinochet arrested in London on October 16, 1998. But it is because of his loving support and guidance that I did. Pinochet’s detention gave rise to a cry of joy across the world. Elizabeth and I were ecstatic! Jack Lemmon called to congratulate us, as did Costa-Gavras. Pinochet’s arrest, in response to a request by Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzón to hold him on charges in London for extradition to Madrid for crimes against humanity, was the first indication that the dictator would actually be held accountable. His arrest represented a major vindication for all of his victims.

Thank you, Orlando Letelier, for working so hard, along with Saul Landau and the Institute for Policy Studies, to tell the truth about the violent crimes of the dictatorship until your assassination, by order of Pinochet, on the streets of Washington brought your powerful voice to an end.

Thank you, Peter Weiss, Nancy Stearns, Rhonda Copelon, John Corwin, and the Center for Constitutional Rights, for your pro bono suit on behalf of the Horman family against Henry Kissinger.

Thank you, Joan Garcés, for starting the process in Spain to sue Pinochet’s Chile for harm against Spaniards, a process that laid the groundwork for universal jurisdiction.

Thank you, Judge Garzón, for issuing the arrest warrant that Britain’s Foreign Secretary Jack Straw honored, which kept Pinochet under house arrest in London for 18 months.

Thank you, Jeremy Corbyn, member of parliament, for urging me to come to London to protest the first decision of the Law Lords, which gave blanket sovereign immunity to Pinochet, and for prevailing on me to testify in the House of Commons. It hadn’t occurred to me to do so, but on reflection I thought it a very good idea. In London, a leader of the Chile solidarity movement, Diane Dixon, was organizing many forms of protest; one of the most moving was an opportunity to testify to Pinochet’s crimes in the House of Commons. People who had never publicly told their stories of arrest, torture, and witness to crimes did so for the first time. It was a profound process, which demonstrated to everyone just how important each testimony was. We were all connected by our horrific experiences, and we were all empowered by testifying together against Pinochet’s brutal regime.

In March 2000, the Law Lords reversed themselves and ruled that sovereign immunity did not cover heinous crimes against humanity and that Pinochet could be extradited to Spain. If Pinochet’s lawyers and other enablers – the late Margaret Thatcher among them – hadn’t lobbied for his release on the grounds of old age and mental infirmity, he would have actually been put on trial in Madrid.

Instead, Pinochet returned to Chile. He believed he had escaped justice. But in the country where he had been a bloody dictator, he now found a special investigative judge ready to bring human rights crimes charges against him.

Thank you, Judge Juan Guzmán Tapia, who was initially not provided a phone, file cabinets, or heat for his basement “office.”

As Judge Guzmán began receiving multiple cases against Pinochet and his top officers, I traveled to Chile in December 2000 to file a case with the help of our Chilean attorneys Fabiola Letelier and Sergio Corvalán for the wrongful death of my husband. It felt like the right thing to do.

I remember the compassionate manner in which Judge Guzmán took our testimony in English and Spanish. His effort to pursue the Horman case proved resilient in the face of obstructions by the military. He even recreated crimes in the National Stadium and recorded them on video, to substantiate testimonies of people who survived being taken there after the coup. The film “The Judge and the General” eloquently tells the story of Judge Guzmán’s conversion to a full understanding of Pinochet’s human rights crimes.

As Judge Guzmán dedicated himself to prosecuting General Pinochet, a number of his cases were transferred to Judge Jorge Zepeda – including ours. After indicting Pinochet for more human rights crimes in December 2004, and ordering the former dictator placed under house arrest, Judge Guzmán retired.

Thank you, Judge Zepeda. Thank you Sergio Corvalán and Fabiola Letelier, for representing our case against Pinochet’s regime for 13 years and two investigating judges so far.

In November 2011, Judge Zepeda indicted a Chilean intelligence officer, Pedro Espinosa, as well as the former head of the U.S. Military Group, Captain Ray Davis, for complicity in the deaths of Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi. In October 2012, the Supreme Court of Chile approved Zepeda’s order for a formal extradition request to the United States for Davis. Nine months later, in July 2013, the Chilean government was still officially translating the request. When finished, Chile’s Foreign Ministry will forward the request to the Chilean Ambassador in Washington, D.C., to give to the State Department. The indictment and extradition request appear to tie a U.S. military official directly to the killing of two U.S. citizens in Chile.

I am filled with so much gratitude for the people who demanded the truth be told over the years.

A special thank you to Senator Frank Church, for his committee’s investigation of foreign assassinations and the discovery that rifles with no serial numbers had been sent through the U.S. diplomatic pouch to anti-Allende groups.

Thank you to Senator Patrick Moynihan, for taking an interest in our case.

Thank you to Senator Ted Kennedy, for being in the National Stadium in Santiago in 1990 to exorcise tortured ghosts and at the same time to celebrate the inauguration of Patricio Aylwin, the first elected president after the plebiscite that brought Pinochet’s dictatorship to a close.

Thank you, Senator Tom Harkin, for speaking up about Pinochet’s atrocities and standing up for human rights.

Thank you, Representative Maurice Hinchey, for your crucial amendment requiring the CIA to report to Congress on all of its activities leading up to Allende’s overthrow.

Thank you, Peter Kornbluh and the National Security Archive for working with the Clinton Administration to declassify and release documents about the Chilean coup and for finding the one such document that told us that the State Department thought that the U.S. officials were either complicit in or looked away from Chile’s threat to Charles’ life – and Frank Teruggi’s – ignoring their duty to protect the lives of American citizens.

Thank you, Ambassador John O’Leary, for arranging to take the entire collection of 24,000 records to Chile for use by Chilean lawyers, journalists and legal libraries and for pushing the State Department to post them all on the Internet.

Thank you Joan Baez, Jackson Browne, Ariel Dorfman, Judy Dworin, Bob Dylan, Patricio Guzmán, Inti Illimani, Walter Locke, Holly Near, Phil Ochs, Ángel Parra, Quilapayun, Jorge Reyes, Deborah Shaffer, Sting, and many other musicians, writers, filmmakers, dancers, and artists who told the story of the destruction of Chile’s democracy and the horror of the aftermath to audiences small and large around the world.

Thank you, Patricia Verdugo, for daring to publish your investigation of Pinochet’s “Caravan of Death,” “The Clawings of the Puma,” while the dictator was still in power.

Thank you, Joan Jara, for your fight for justice for Victor, who inspired so many with his guitar and his courage.

Thank you, Pat Bennetts, for getting to the bottom of the torture and death of your brother, Father Michael Woodward, on the Chilean naval vessel Esmeralda.

Thank you, exiled Chileans, who struggled with your shock and sadness to tell the horror story of your and your family’s experiences for the world to know.

On September 9, 2013, the Charles Horman Truth Foundation hosted a “Tribute to Justice” to mark 40 years since the coup d’état in Chile. We honored the legal authorities who have advanced the prosecution of human rights crimes. We gathered to reflect on the global struggle to get at the truth. This event was held at the Christian Science church in New York City that was founded and attended by Charles’ parents, Ed and Elizabeth, both of whom were no longer here to share this meaningful anniversary. It is the church where Charles went to Sunday school as a youth. I felt his spirit as we commemorated the pursuit of justice, peace and dignity in Chile and the world – the very goals to which my Charlie dedicated, and sacrificed, his beautiful life.

I’ve endured the decades thanks to some wonderfully courageous people.

Joyce Horman is the founder of the Charles Horman Truth Foundation This article previously appeared in The Progressive magazine, September 2013, Vol. 77 Issue 9, pp. 16-19. A few minor edits were made to reflect the passage of time since its writing.

Banned in Chile

By Norman Stockwell

The 1982 film “Missing” by Greek-born director Costa-Gavras (Konstantinos Gavras) opens with a director’s statement: “This film is based on a true story. The incidents and facts are documented.” Costa-Gavras co-wrote the screenplay based on the book “The Execution of Charles Horman: An American Sacrifice” (1978) by attorney Thomas Hauser. (After the film’s release, the book was republished under the title “Missing” in 1982.) Like Costa-Gavras’ other film work (including films like “Z” about the military coup in Greece and “State of Siege” about the Tumpamaros and the role of the USAID in Uruguay) is political. It asks questions, and asks us, the viewers, to seek answers.

Even though the film won an Academy Award for Best Writing as well as numerous other international festival awards, its veracity was challenged in the press and in a lawsuit for defamation by former U.S. Ambassador to Chile Nathaniel Davis. The film was banned in Chile during the years of Pinochet’s dictatorship, and according to a 1982 New York Times review, two days before the film’s premiere in New York City, the U.S. State Department released a statement saying, “ The department takes issue with a number of facts in the film and just about all of its conclusions.” Despite the U.S. government’s denials, a court in Chile earlier this year (on June 30, 2014) ruled that U.S. Naval intelligence officer Captain Ray E. Davis (called “Ray Tower” in the film) was culpable in the deaths of Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi.

Jack Lemmon gives a powerful performance as Charles Horman’s father, and together with Sissy Spacek as Joyce Horman, allows a U.S. audience to identify with the characters in the film, feel their trauma, and join them in seeking answers. Both were nominated for Oscars for their performances, and movie critic Roger Ebert said at the time: “Lemmon and Spacek are about as good an example of Ordinary Americans as you can find in a movie.”

Despite its controversial subject matter, the film opened in 733 theaters across the United States in 1982,and was just rereleased a few years ago in a two-DVD set by the Criterion Collection.

Kissinger: The declassified record on regime change

By Peter Kornbluh

This article originally appeared at The National Security Archive on September 11, 2013, on the 40th anniversary of the coup in Chile. Some references to the date of publication are unchanged and therefore no longer current.

Henry Kissinger urged U.S. President Richard Nixon to overthrow the democratically elected Allende government in Chile because his “‘model’ effect can be insidious,” according to documents posted today (Sept. 11, 2013) by the National Security Archive. The coup against Allende occurred on this date 40 years ago. The posted records spotlight Kissinger’s role as the principal policy architect of U.S. efforts to oust the Chilean leader, and assist in the consolidation of the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile.

The documents, which include transcripts of Kissinger’s “telcons” – telephone conversations – that were never shown to the special Senate Committee chaired by Senator Frank Church in the mid-1970s, provide key details about the arguments, decisions, and operations Kissinger made and supervised during his tenure as national security adviser and secretary of state.

“These documents provide the verdict of history on Kissinger’s singular contribution to the denouement of democracy and rise of dictatorship in Chile,” said Peter Kornbluh, who directs the Chile Documentation Project at the National Security Archive. “They are the evidence of his accountability for the events of 40 years ago.”

Today’s posting includes a Kissinger telcon with Nixon that records their first conversation after the coup. During the conversation Kissinger tells Nixon that the U.S. had “helped” the coup. “[Word omitted] created the conditions as best as possible.” When Nixon complained about the “liberal crap” in the media about Allende’s overthrow, Kissinger advised him: “In the Eisenhower period, we would be heroes.”

That telcon is published for the first time in the newly revised edition of Kornbluh’s book, “The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability” (The New Press, 2013), which has been re-released for the 40th anniversary of the coup. Several of the other documents posted today appeared for the first time in the original edition, which the Los Angeles Times listed as a “Best Book” of 2003.

Among the key revelations in the documents:

- On September 12, eight days after Allende’s election, Kissinger initiated discussion on the telephone with CIA director Richard Helm’s about a preemptive coup in Chile. “We will not let Chile go down the drain,” Kissinger declared. “I am with you,” Helms responded. Their conversation took place three days before President Nixon, in a 15-minute meeting that included Kissinger, ordered the CIA to “make the economy scream,” and named Kissinger as the supervisor of the covert efforts to keep Allende from being inaugurated. Since the Kissinger/Helms telcon was not known to the Church Committee, the Senate report on U.S. intervention in Chile and subsequent histories date the initiation of U.S. efforts to sponsor regime change in Chile to the September 15 meeting.

- Kissinger ignored a recommendation from his top deputy on the NSC, Viron Vaky, who strongly advised against covert action to undermine Allende. On September 14, Vaky wrote a memo to Kissinger arguing that coup plotting would lead to “widespread violence and even insurrection.” He also argued that such a policy was immoral: “What we propose is patently a violation of our own principles and policy tenets. … If these principles have any meaning, we normally depart from them only to meet the gravest threat to us, e.g. to our survival. Is Allende a mortal threat to the U.S.? It is hard to argue this.”

- After U.S. covert operations, which led to the assassination of Chilean Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces Gen. Rene Schneider, failed to stop Allende’s inauguration on November 4, 1970, Kissinger lobbied President Nixon to reject the State Department’s recommendation that the U.S. seek a modus vivendi with Allende. In an eight-page secret briefing paper that provided Kissinger’s clearest rationale for regime change in Chile, he emphasized to Nixon that “the election of Allende as president of Chile poses for us one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere,” and “your decision as to what to do about it may be the most historic and difficult foreign affairs decision you will make this year.” Not only were a billion dollars of U.S. investments at stake, Kissinger reported, but what he called “the insidious model effect” of his democratic election. There was no way for the U.S. to deny Allende’s legitimacy, Kissinger noted, and if he succeeded in peacefully reallocating resources in Chile in a socialist direction, other countries might follow suit. “The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile would surely have an impact on – and even precedent value for – other parts of the world, especially in Italy; the imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.” The next day Nixon made it clear to the entire National Security Council that the policy would be to bring Allende down. “Our main concern,” he stated, “is the prospect that he can consolidate himself and the picture projected to the world will be his success.”

- In the days following the coup, Kissinger ignored the concerns of his top State Department aides about the massive repression by the new military regime. He sent secret instructions to his ambassador to convey to Pinochet “our strongest desires to cooperate closely and establish firm basis for cordial and most constructive relationship.” When his assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs asked him what to tell Congress about the reports of hundreds of people being killed in the days following the coup, he issued these instructions: “I think we should understand our policy that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was.” The United States assisted the Pinochet regime in consolidating, through economic and military aide, diplomatic support and CIA assistance in creating Chile’s infamous secret police agency, DINA.

- At the height of Pinochet’s repression in 1975, Secretary Kissinger met with the Chilean foreign minister, Adm. Patricio Carvajal. Instead of taking the opportunity to press the military regime to improve its human rights record, Kissinger opened the meeting by disparaging his own staff for putting the issue of human rights on the agenda. “I read the briefing paper for this meeting and it was nothing but human rights,” he told Carvajal. “The State Department is made up of people who have a vocation for the ministry. Because there are not enough churches for them, they went into the Department of State.”

- As Secretary Kissinger prepared to meet Gen. Augusto Pinochet in Santiago in June 1976, his top deputy for Latin America, William D. Rogers, advised him to press the dictator to “improve human rights practices” and make human rights central to U.S.-Chilean relations and to press the dictator to “improve human rights practices.” Instead, a declassified transcript of their conversation reveals, Kissinger told Pinochet that his regime was a victim of leftist propaganda on human rights. “In the United States, as you know, we are sympathetic with what you are trying to do here,” Kissinger told Pinochet. “We want to help, not undermine you. You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende.”

At a special “Tribute to Justice” on September 9, 2013, in New York, Kornbluh received the Charles Horman Truth Foundation Award for the Archive’s work in obtaining the declassification of thousands of formerly secret documents on Chile after Pinochet’s arrest in London in October 1998. Other awardees included Spanish Judge Baltazar Garzón who had Pinochet detained in London, and Chilean Judge Juan Guzmán who prosecuted him after he returned to Chile in 2000.

________________________________________

THE DOCUMENTS

Document 1: Telcon, Helms – Kissinger, September 12, 1970, 12:00 noon.

Document 2: Viron Vaky to Kissinger, “Chile – 40 Committee Meeting, Monday – September 14,” September 14, 1970.

Document 3: Handwritten notes, Richard Helms, “Meeting with President,” September 15, 1970.

Document 4: White House, Kissinger, Memorandum for the President, “Subject: NSC Meeting, November 6-Chile,” November 5, 1970.

Document 5: Kissinger, Memorandum for the President, “Covert Action Program-Chile, November 25, 1970.

Document 6: National Security Council, Memorandum, Jeanne W. Davis to Kissinger, “Minutes of the WSAG Meeting of September 12, 1973,” September 13, 1973.

Document 7: Telcon, Kissinger – Nixon, September 16, 1973, 11:50 a.m.

Document 8: Department of State, Memorandum, “Secretary’s Staff Meeting, October 1, 1973: Summary of Decisions,” October 4, 1973, (excerpt).

Document 9: Department of State, Memorandum of Conversation, “Secretary’s Meeting with Foreign Minister Carvajal, September 29, 1975.

Document 10: Department of State, Memorandum of Conversation, “U.S.-Chilean Relations,” (Kissinger – Pinochet), June 8, 1976.

The Pinochet Affair: State terrorism and global justice

By Roger Burbach

Following is an excerpt of Roger Burbach’s book “The Pinochet Affair: State Terrorism and Global Justice.” It is reprinted here with permission from the author.

There is some kind of poetic justice and even Shakespearean drama involved in Joan Garcés’ survival on September 11, 1973. Historical literature and medieval fiction entertain the notion that as you take over the king’s palace, you slay the ruler and his entourage. Family members, key advisers, the dauphin, the chamberlain and anyone who could avenge the ousted king are slaughtered. Joan Garcés, who managed to survive the assault on the Moneda Palace, has come to corroborate the old theory that the usurping prince needs to eliminate all in the palace or they will come back to haunt you.

Augusto Pinochet and his associates may have never read medieval history, but in the aftermath of the coup they certainly did their best to get rid of Allende’s cabinet, advisers, loyal military officers and security guards. Most of those who did not die or escape on the day of the coup were imprisoned on Dawson Island, located in the remote and icy lands of southern Chile. Some, like José Tohá, who held several high-level ministerial positions under Allende, including Minister of Defense, were tortured and died. But Pinochet’s campaign of physical intimidation and elimination was by no means complete, as he himself recognized.

Years later, in early 1998, when he was attending a military conference in Quito, Ecuador, he was asked about Garcés’ filing of charges against him in Valencia, Spain, for his crimes as head of state. Pinochet arrogantly responded: “We had him in prison and let him go!” As Garcés says, “I was never imprisoned by Pinochet but he appears to be expressing some deep Freudian desire to relive those days so he can succeed in capturing and getting rid of me.” This historical mistake would end up costing the usurping prince his freedom, almost exactly a quarter of a century after the destruction of the Moneda Palace in Santiago.

Garcés returned to Spain in 1973 with his dreams shattered, but devoted to the memory of Allende. Just 29 in 1973, he probably would have remained in Chile indefinitely had it not been for the coup. In Spain he set up the Salvador Allende Foundation and wrote a book, “Allende and the Chilean Experience: The Arms of Politics.”

Garcés’ volume is a detached account of his experiences during the three years he worked as Allende’s adviser. What seems most puzzling about the book is the distance he takes in recalling the last hours of the presidency. Garcés was one of the few who escaped the carnage, yet he writes about the episode almost as if he had not been there. It may have been the pain he carried inside and the attachment he developed toward Allende that made Garcés appear laconic and almost devoid of feelings in the recounting of the moments in which the Chilean experiment in democratic socialism came to an end.

Garcés has undergone a physical mimesis as he approaches the age Allende was when he first met him. Garcés almost looks like the son Allende never had. He sports a moustache the same as Allende’s, has a similar broad face and physical profile, and wears glasses on occasion. Garcés is a taciturn and yet modest man, giving the impression that he is always preoccupied with something. He refuses to talk about his central role in bringing Pinochet to justice, and is very reluctant to give interviews to journalists. He says, “My role is really not very important.”

His modesty is almost out of place; nor does it fit the deed. If it had not been for Garcés’ singular determination, to prosecute the case of Antoni Llido, a Spanish priest tortured and disappeared in Chile in 1974, Judge Baltasar Garzón Real in Madrid would not have requested the extradition of Pinochet for trial in Spain. There were very few Chileans residing in Spain who could press for legal action against Pinochet because at the time of the Chilean coup General Francisco Franco still held on to power in Spain. Most Chileans fleeing their homeland for Europe in 1973 and 1974 wound up in countries like England, the Netherlands and Sweden where social-democratic parties were in office.

Judge Garzón’s first efforts in Spain to prosecute former dictators were directed against the Argentine military rulers rather than Pinochet. Argentines always had a much larger presence in Spain than Chileans, primarily because around the turn of the century there was a heavy Spanish migration to Argentina, with many families to this day maintaining dual citizenship. Because the Argentine coup occurred in 1976, a year after Franco’s death, thousands of Argentines fled or returned to Spain, giving them a substantial social base to agitate for legal action against the military junta. This explains in large part why in 1996 Judge Baltasar Garzón, who sat on the National Court of Spain, began investigating the Argentine military leaders, just a few months before Garcés filed his case against Pinochet in Valencia.