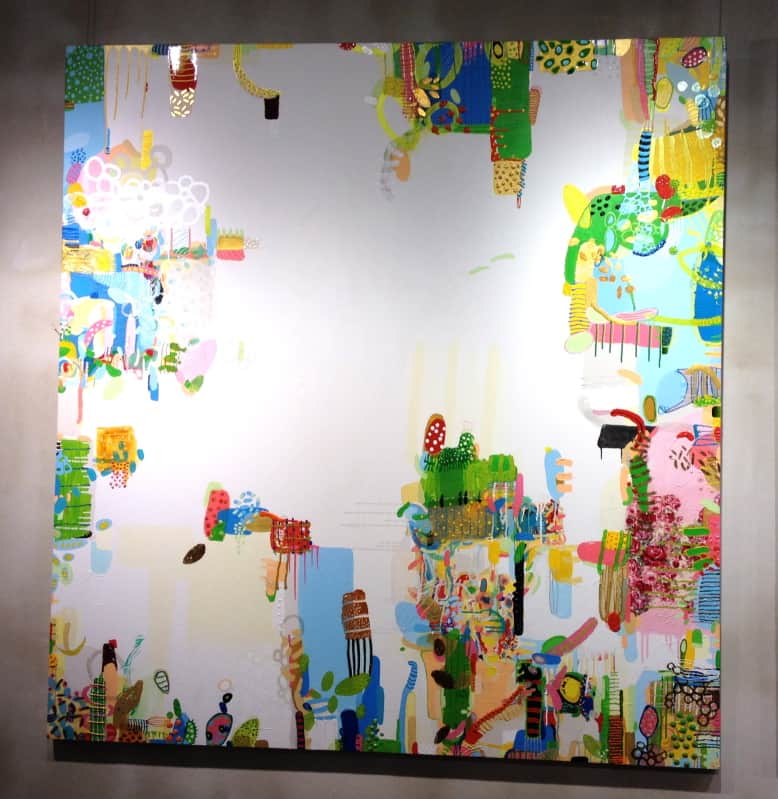

The painting is enormous. It’s so big, you would need an entire living room to display it. And you can’t miss it – if you’re walking past the Wasserman gallery in the swanky Avenida Escazú mall, the giant plate-glass windows force you to see the painting. Not only is it big, but its bright colors, surreal shapes, and blinding white space in the middle also mesmerize the eye. You almost have to stop, look at it, and wonder what it’s supposed to be.

Esteban Fernández Acosta sits at the gallery’s desk. He’s an affable and laid-back 33-year-old. He works here partly because he’s a friend of the owner, Lazaro Wasserman, and partly because he’s an artist himself. Indeed, Fernández painted the enormous canvas hanging to his right.

“I painted it in my studio in Rohrmoser,” says Fernández nonchalantly. “It took me two or three months. I had to. It’s big.” He calls the painting “Tropicalismo Social.”

“It’s a mixture of abstract forms,” says Fernández. He adds that he found inspiration in tropical colors, the warm greens and overlapping texture of the rain forest. While the jazzy shapes are reminiscent of Dr. Seuss, the brightness is pure Central America.

“I was a graphic designer and a photographer,” Fernández recalls. But little by little, he became more interested in fine art, known in Spanish as “artes plásticas.” While he still photographs, fine art has become the focus of his career. “It’s hard. There’s only a small market. The arts community is very closed off. But I like it.”

Ever since I first arrived in Costa Rica, I have been curious about its visual arts – not just the museums and academies, but its commercial galleries, its professional artists, and the people who actively collect paintings and sculpture. In every beach town, there is a tienda selling artwork. Much of this stock, such as the wooden figures and masks, is mass-produced in other countries, but many of the landscapes and carvings are created by individual artists living in Costa Rica. Entire galleries are dedicated to local work, and their locations vary from inner city San José to the highlands of Monteverde. Some vendors are entirely virtual. Some artists hawk their own work at local fairs.

Costa Rica is not famous for its arts scene, and the creative community is scattered throughout the country. As Fernández suggests, artists can be cliquey and intensely private. If the artists are hard to categorize, the buyers are nearly impossible. But as I made my rounds of the commercial art scene, I found certain patterns. Art is alive in Costa Rica, and it’s richer than any passing visitor could imagine.

The Art Biz

“It’s not a business,” says Marta Antillón. “Business is a cold thing. It’s a passion.”

Not everybody could convincingly make this statement, but Marta Antillón is an exception: Her face is vibrant, she dresses elegantly, and she has the general flair of a bygone age. You could picture Antillón on Madison Avenue in the 1950s. Her venue is Galería Valanti, in Barrio Escalante, a converted domicile that is as fashionable as she is.

Hanging in the bright and open rooms are a variety of paintings, most of them zesty and energetic. One eye-catching example is Carlos Tapia’s massive skyline, “Año Nuevo en Nueva York,” whose candy-colored buildings swirl around the viewer like a hallucination.

Antillón has been collecting and dealing artwork for 40 years. She studied fine arts in school, she is an adept painter herself, and she has traveled widely. She prefers contemporary work, and she is extremely discriminating: If an artist has a good reputation and comes recommended, she will review a portfolio, but Antillón claims she has never discovered a new artist by accident.

Some 280 kilometers away, on a highway leading out of the northwestern city of Liberia, stands Hidden Garden, an art gallery that is opposite of Valanti in almost every way. The owners are Greg and Charlene Golojuch, a U.S. couple that had very little background in art before moving to Costa Rica in 2008. They partnered with Carlos Hiller, an Argentine native who largely paints realistic portraits of fish.

“Costa Rica is not known for art, like Santa Fe, Spain, Italy,” says Charlene Golojuch. “But we’re trying to improve the perception. There are really talented people here. With 60 artists, we have a lot of variety.”

Hidden Garden is a generous space: The 15 rooms are packed with original works, and Golojuch estimates that 80 percent of the artists they represent are native Costa Ricans.

While Galaría Valanti usually makes appointments with individual buyers, Hidden Gallery relies mostly on random customers stopping in.

“I wish there was consistency,” Golojuch says with a laugh. “I wish I could put my thumb on the perfect clientele. We get such variety. We get people who know art and are looking for something very specific, and the dollar amount doesn’t matter. We get a lot of Canadians – we like the Canadians. Then we get the tourists, who come through [Guanacaste] for a week or two.”

“This past high season was a record-breaker for us,” she adds. “But the low season is sporadic. We might have a day when 25 people come through, and then no one for a day or two. But each high season seems to get better.”

So what kind of person walks through Hidden Garden’s door, or calls Galaría Valanti, and buys a $1,000 painting?

“You get some tourists,” says Golojuch. “But you also have people who are decorating their homes.”

“Every type of person knows my gallery,” says Antillón. “Some find us on the Internet. But everyone who likes art comes here.”

When it comes to art collectors, the obvious demographic is older, wealthy, and landholding. This would explain why the mecca of high-end art galleries is Escazú, a highly Americanized suburb in the hills above San José. In a district famous for its country club and luxury condos, it’s perhaps no wonder that the “Beverly Hills of Costa Rica” has a high concentration of art dealers.

But when I visited Fernández at the Wasserman gallery, located in the heart of this high-income area, he described a younger clientele.

Asked who buys art at the gallery, he responds, “Some foreigners, but not many. This type of contemporary art appeals to younger people, 25 to 35 years old. They have a new house, they want to decorate it. Of course most of our clients are older and have some money, but for the contemporary style, mostly younger people are interested in it.”

A National Style?

One question burns to be asked: What is Costa Rican art? What makes the art here distinct? If an art historian can identify Japanese brushstrokes or Byzantine frescoes from a mile away, what patterns and images are common among Costa Rican artists?

No one I talked with could answer that question. Most people seemed uncomfortable, as if I had asked them to describe what God looked like. The question was too broad to answer, or perhaps they were too close to the subject to see it holistically. Or maybe there are no commonalities.

“Each artist has his own style,” declared Antillón during my visit. “But there is no Costa Rican style. Each is different.”

But the tradition of Costa Rican art does have clear roots, and although Tico artists are not as historically consistent as, say, the Hudson River School, certain themes and styles permeate nearly every gallery and museum in the country.

To help me understand the basic history of Costa Rican art, my boss Jonathan loaned me his weighty coffee-table book, “Arte Costarricense: Un Siglo” (“Costa Rican Art: A Century”) by José Miguel Rojas. The book is gorgeously illustrated with color prints, showing paintings and sculptures crafted between the mid-19th century and 2003, when the book’s first edition was published.

Like much of Latin America, Costa Rica’s culture is a collision of Native American, Spanish, and Afro-Caribbean influences, and you can see evidence of that the second you arrive at the airport: Boruca masks hang in the souvenir shop, each carved from balsawood and elaborately painted according to indigenous tradition. Landscapes of campesinos working their farms are everywhere, as well as portraits of women dancing in frilly dresses. Folk customs like máscaras and colorful ox-carts are national icons. Many people see these works as old-fashioned and touristy, but they also form the foundation of Costa Rican identity. As the old saying goes, they are as Tico as gallo pinto.

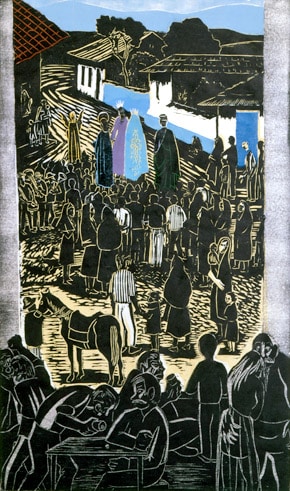

“Arte Costarricense” shows how art evolved in the 20th century, echoing the modernist movement that was taking place all over the world: Paintings became more impressionistic, then abstract. Sculptures became more conceptual than realistic. But even today, the Indo-Afro-Iberian influence is still evident everywhere. Catholicism is still a powerful theme, as is working-class labor.

However, perhaps the most popular theme is the land itself. Most of this verdant tropical country has been modestly developed. Cultures tend to paint with the color palette they see every day, so it’s no surprise that traditional Costa Rican paintings have vibrant hues. Landscapes are filled with lush foliage, sprawling fields, dense rain forest, and every kind of flower and fruit. Animals are routinely cast as central characters. In certain galleries, you can’t throw a paintbrush without hitting a toucan.

One of the most notable artists to paint traditional Costa Rican life was Fausto Pacheco, who spent his career recreating cottages and bridges on canvas. More recently, the artist Lisandro López Baylon, a native of Argentina who resides in Costa Rica, continues that tradition with his realistic watercolors of everyday people, often depicting romanticized historical scenes.

Rules are meant to be broken, especially in art, and to say that Costa Rican art requires certain imagery is like saying that all Spanish art must look like Picasso’s. The works of José Miguel Rojas, for example, are among the most celebrated in the country, but Rojas’ style is belligerent and political, very different from those tranquil portraits of farmers on their fincas.

So, yes, Costa Rica has some clear motifs. But artists don’t like to be pigeonholed. And really, who does?

The Scene

Costa Rican artists aren’t generally well known outside of the country. A rare example is Francisco Almighetti (1907-1998), who has two paintings in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. MoMA also has at least one work by Costa Rican-born sculptor Francisco Zúñiga (1912-1998). These folks are few and far between.

But inside the country, such artists have had a significant impact on the culture. Foreigners may not have heard of Rafa Fernández, but the dreamy portrait painter is acclaimed throughout the country, as are the decades of drawings by Fernando Caballo.

Meanwhile, innumerable young artists are branching off in different styles and directions. With well-stocked art supply stores and many university fine arts programs, aspiring artists have more access and support than ever before.

“Costa Rica is a country that has to be more educated in the artistic realm,” wrote painter Juan Delgado in a recent email to me. Delgado’s story is patently unusual: He was born in Costa Rica, raised and educated in Canada, and has returned to his home country to become a professional artist, where has had astonishing success. The Vatican commissioned Delgado to paint portraits of two popes (Francis and John Paul II), and he is currently working on a September solo show about “extreme poverty.” The exhibit was commissioned by the Club Unión in San José and will show at the Juan Rafael Mora Salon.

“As a young artist, one has the aspirations to go to museums and see art and learn from the past masters of their country,” mused Delgado. “However, that is not the case here. Having visited many museums and galleries in North America and Europe, one has to wait many hours in line every day to be able to get in and appreciate all of the works being displayed. I hope that this trend, this vigor to embrace the magnitude that art can make in our lives, will be valued someday in our country.”

“I am bored by the fascination with the Fausto Pacheco-style country Tico adobe house, with a red roof, white walls, with blue bottom border,” said Donaldo Voelker, a U.S.-born landscape painter who moved to Costa Rica in 2004 and has had 13 exhibitions. Voelker says he started painting at 57 and studied with five different art teachers, mostly in Heredia. His training has taken place entirely in Costa Rica, and he has developed strong feelings about the direction of the regional art scene.

“I find Tico artists too interested in surrealism, which I do not believe reflects the soul of Costa Rica,” he told me recently. “I believe Tico artists should better interpret Costa Rica in impressionist oil renderings, such as by the greats Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Cézanne.”

Artists in all cultures are famous for their feisty opinions and desire to rebel and innovate. As Costa Rica’s artists go about creating, dealers and collectors get to reap the rewards – an increasingly complex body of work, more available than ever, in a still-obscure marketplace.

“It’s part of our job to expose artists, help them grow,” said Ilan Izrael as he showed me around D’Art Galería in Escazú. The business really belongs to Izrael’s mother, Frida Najman, but because she was out of the country during my visit, Izrael took it upon himself to show me around.

The first floor of D’Art is a fairly typical frame shop: There are lots of generic posters and reproductions hanging on the walls and stacked on the floor. D’Art’s framers can help customers select from 500 different moldings. Most of this work on display is overtly commercial, the kind of stuff you would buy at Crate & Barrel.

Then Izrael led me to the second floor. “It’s a mess right now,” he said apologetically. “I’m planning to have everything arranged by Friday.”

But what a mess: The second floor is where D’Art shows its real collection, complete with massive canvases and sculptures worthy of the Smithsonian. Indeed, many of those famous Costa Rican names are represented here.

“Of course you know Rafa Fernández,” said Izrael, gesturing to one of the paintings. Then he nodded at one of the sculptures. “And Francisco Zúñiga is a very famous Costa Rican artist as well.”

D’Art is only three years old, but Fernández’s family has enjoyed healthy doses of success. Not only have they stayed solvent in one of the most expensive districts in the country, but they have also attracted some remarkable artists from Costa Rica and beyond. Fernández showed me a large-format photograph of a rainbow striking a Caribbean island. He identified the artist as Tomás Sánchez, an acclaimed Cuban painter and engraver who also takes photographs.

“It’s a harsh market,” admitted Izrael. After running several clothing stores in San José, Izrael’s parents decided to close their operations and open an art gallery instead. (Izrael has historically worked as an auto mechanic.) Najman herself enjoys painting, but she does not show her own work.

“We separate the work,” said Izrael. “[D’Art] is not for amateurs. We have artists with long [résumés]. Sometimes people come to frame their artwork, and they tell us about the artist. Sometimes the artists come to us with examples of their work.”

Izrael then told me about the gallery’s relationship with Bacchus Mediterranean Restaurant in Santa Ana. The eatery regularly hangs fine art, curated by D’Art, and hosts semi-private opening parties. Izrael said the next exhibit would incorporate 20-30 pieces.

As I left D’Art, I was reminded of my final moments with Antillón, back at Galería Valanti. Toward the end of our conversation, Antillón said that she had a fine private collection, which was not visible to the public. This prompted me to ask my most pressing question.

“When you look for new artists and new works,” I said, “what are you looking for?”

Antillón smiled.

“Quality.”