MARCH 8 is International Women’s Day. Costa Rica’s women didn’t get to vote in a national election until 1953, but that doesn’t mean they were slow in agitating for their rights – or that they won them easily. The night of Aug. 2, 1947, is still remembered by many. Earlier that day, 8,000 women dressed in black marched to the Casa Presidencial to petition their right to vote.

There, they decided to rally at the Parque Nacional, and stay all night if necessary, until their demands were met. But at 11:30 p.m. the lights in the area were turned off, creating panic. In the dark, police started shooting in the air; they caused no injuries but scattered the women – andstrengthened their resolve.

Although some election reforms were discussed and passed in the Assembly the next day, they did not favor the women. The early1940s was an era of social turmoil, and a national work stoppage, la huelga de brazos caídos (“the strike of lowered arms”), was followedby government oppression that did not stop people from agitating for reforms.

In 1948, the national election was annulled, and a civil war ensued. It wasn’t until June 1949, more than a year after the civil war, that the interim government headed by Pepe Figueres approved a change in election laws allowing women to vote in the next national election.

A few women got a taste of the ballot box earlier. On July 30,1950, 349 women in the districts of La Fortuna and La Tigra, in the Northern Zone, voted in a referendum to separate from the canton of San Ramón and form the canton of San Carlos. They were the first of their sex to vote in Costa Rica.

For the 1953 special election, women organized to sign up other women for cédulas, or identity cards, so that they could vote. Sister Miriam Keith, whose mother and aunt had participated in marches for women’s rights, was a teenager at the time and went with a neighbor to the Cooperativo Victoria in Grecia. “This was in the summer of ‘49 or ‘50. The women were waiting in a line when we got there,” she reported. “But some were concerned about what their husbands would say.

One woman said her husband told her only prostitutes had cédulas. ”FORMER ambassador to Israel and Minister of Culture, Carmen Naranjo, was another teenager who helped get out the vote, passing out literature door to door. “Some people laughed at us,” she recalled. “Others were sympathetic, but nobody insulted us.

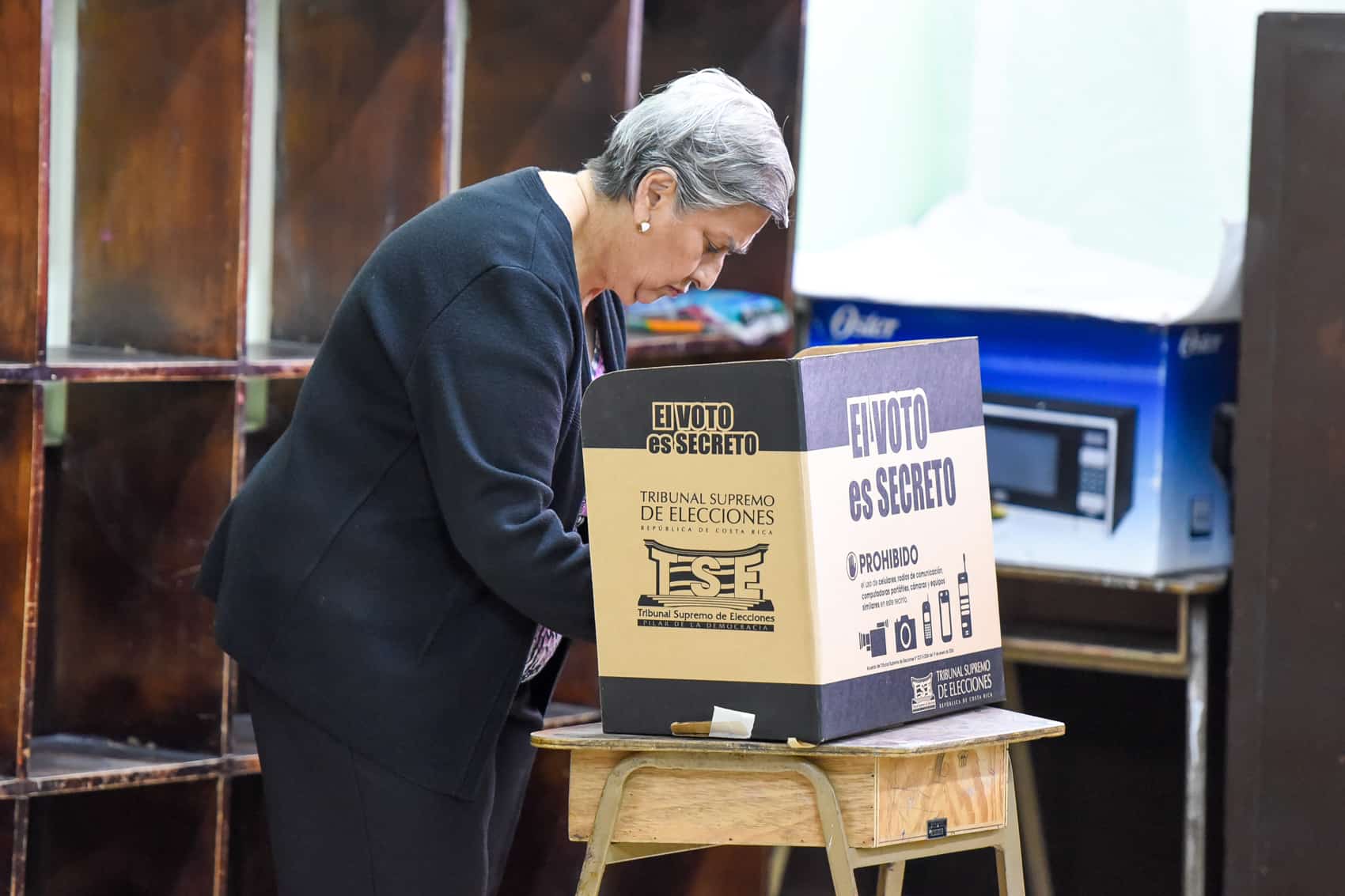

At the time, some people felt it was giving men two votes because the women would vote the way their husbands told them, like an order. But that didn’t happen. You saw cars with one party flag on the driver’s side and a different party flag on the passenger side. ”According to Naranjo, women accompanied each other to the polls, where there were women poll watchers. No record exists of how many women voted; breakdowns by sex were not recorded until 1986.

There have always been outspoken women in Costa Rica’s history. Pancha Carrasco’s use of a flintlock rifle in the campaign of 1856 helped Tico troops win the battle of Rivas, and women took to the street to protest strongman General Morazán’s rule in the 1840s. In the 1890s, women’s organizations were active in claiming the right to elect – not an easy task, given the small and scattered population. President José Joaquín Rodríguez promoted the voto feminino (women’s vote), but it wasn’t taken seriously.

In 1917, deputy Álvaro Quirós proposed that a woman “over21, known to be honest, (who) had finished grade school or had means of ¢3,000 or more, or (who) was a widow with at least five children, be given the vote.” Of 36 deputies, 20 voted against it. By the 1920s, organizations led by educator and author Dr. Emma Gamboa, Costa Rica’s first woman lawyer, Ángela Acuña Brown, and political activist and author Carmen Lyra actively sought the vote with marches, rallies, pamphlets and speeches that were not popular with the press. One cartoon showed a woman sitting and reading while her husband tried to manage a pair of neglected children.

A conservative group claimed “political participation was a symbol of the degradation of the appropriate attributes of women,” and another wrote “the home is the exclusive space for women and (they)should be happy with domesticity.” Presidential candidate for1924, Jorge Volio, proposed female suffrage but lost the election.

Even winning the vote did not guarantee equality for women, said Naranjo. When she became Minister of Culture in 1974, shewas only the third woman in government. “That’s why we needed the law for equality for women,” she said.