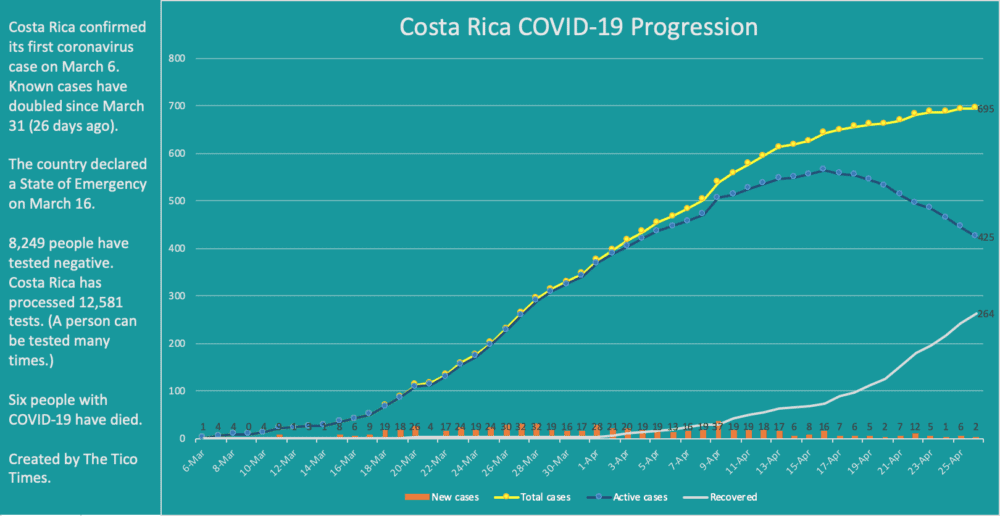

Costa Rica has flattened the curve.

In nine of the last 10 days, Costa Rica has added single-digit new coronavirus cases. Over that span, recoveries (176) have significantly outpaced new positive cases (46).

While the country has reported six COVID-19-related deaths, at no point have the country’s health services been overwhelmed due to the pandemic. The coronavirus-specific hospital Costa Rica built has remained largely empty since it was inaugurated last month.

How has Costa Rica contained the coronavirus pandemic? We take a look at some possible explanations.

An early, nationwide response

Costa Rica began preparing for the coronavirus before it is known to have arrived in the country. By late February, the Health Ministry had established a contact-tracing protocol and was requiring businesses to adopt specific disinfection measures.

On March 9, before Costa Rica confirmed its tenth case of the coronavirus, it suspended mass gatherings and told employees to work from home. A week later, before Costa Rica’s first COVID-19 death, the country entered a State of Emergency — closing the border to arriving tourists and canceling in-person school, among other measures.

Communication from authorities has been informative and consistent. The Health Ministry — headed by Daniel Salas, who has a medical degree, a background in epidemiology and a degree in public health — leads a nationally televised press conference at the same time every day. While some recommendations (whether to close the borders, for instance) have changed, the overall theme has persisted that the entire country needs to work together in order to contain the virus.

“We’ve had a very controlled transmission,” Salas said last week. “That’s in large part to the actions taken at the appropriate moment, but also due to the very favorable response from a population that understands the challenge we’re facing.”

A robust public health system

Thanks in large part to Costa Rica’s Social Security System (CCSS, or Caja), more than 90% of the country has medical insurance, according to a 2010 estimate from the Pan-American Health Organization. (This figure includes low-income citizens for which the government pays their healthcare.)

The Caja operates more than 1,000 community health clinics (EBAIS) and two-dozen hospitals. It contracted a charter flight that on Sunday delivered a large shipment of medical supplies and personal protective equipment (PPE) from overseas.

It also conducts coronavirus testing and will provide treatment to uninsured Costa Ricans or visitors.

“We will not make a distinction if you are insured or not insured,” said Román Macaya, the institution’s president, early in the crisis. “This is an issue of national importance.”

The Caja is far from perfect — at least one formal complaint has accused it of denying a test to a patient with COVID-19 symptoms, and it’s struggling financially. But over its nearly 80 years, CCSS has developed into a robust and affordable public health system that is among the most comprehensive in the region.

Lower population and population density

Costa Rica’s population and population density almost certainly help the country control the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus which causes COVID-19.

Costa Rica is a country of just 5 million people. The relatively small population makes it easier for health authorities to conduct contact tracing — the identification of people who may have come into contact with an infected person. Successful contact tracing can limit community spread.

Costa Rica has a population density of 96 people per square kilometer, which is higher than the United States but lower than some hard-hit states, like New York and Florida. And that population is largely in the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM) around the capital, San José, where the country’s most advanced hospitals are located.

Without enforcing an actual quarantine, Costa Rica has kept people home by closing beaches and national parks, and by applying strict driving restrictions at night and on the weekend.

The province of San José has a population density of 323 people per square kilometer, while Puntarenas, Guanacaste and Limón provinces hover closer to 10% of that figure. Population density isn’t necessarily a direct correlation with large-scale community transmission, but Costa Rica has fewer opportunities for mass transmission outside the GAM.

Weather and other factors

In recent days, preliminary lab results have suggested SARS-CoV-2 doesn’t survive as long when exposed to ultraviolet light and humidity.

If true, then Costa Rica may be benefiting from its tropical (hot and humid) climate and its sunny dry season.

“From the beginning, when SARS-CoV-2 began, we noted that the majority of respiratory viruses can last less time in certain conditions in high temperatures and different humidities,” Salas said. (The Health Minister also noted that Panama, which has similar weather, has had much less success containing the virus.)

Costa Rica claims it has had favorable outcomes using hydroxychloroquine to treat some COVID-19 patients, according to the medical manager of the Caja. But the country has not released any data regarding use of the anti-malaria drug, and studies elsewhere have been less promising.

Costa Rica likely has unknown coronavirus cases, though there is some evidence pointing against widespread transmission. In addition to testing everyone who qualifies as a suspected case, authorities conduct 200 sentinel tests each week on samples collected from across the country. As of the Health Ministry’s last report on the subject, on April 19, all of those tests had returned negative.

Walking on fragile ground

Until Costa Rica can conduct widespread antibody testing, it won’t have a full picture of how many people have been infected by the coronavirus.

For now, the Health Ministry says, the country is walking on fragile ground. Because it’s likely the majority of the population hasn’t been exposed to SARS-CoV-2, Costa Rica could still see a rapid rise in cases.

The situation may also be complicated by the arrival of the rainy season, which typically lasts from May-November and brings with it a rise in other respiratory diseases.

“There are clear risks that we could have several pandemic waves,” Salas said.

Monday afternoon, Costa Rican authorities will announce a plan to ease some restrictions. It will be a gradual process, and Salas likened the country’s careful handling of the crisis to a person walking on eggshells.

“We’ve passed a first stage where the number of cases have dropped, but that doesn’t in any moment indicate that we’ve passed beyond a critical period,” he said.