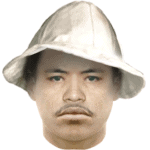

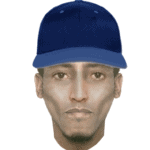

Ten months after the murder of Bribrí indigenous leader Sergio Rojas, Costa Rican authorities appear to be making progress in the investigation, recently releasing a composite sketch of two suspected assailants.

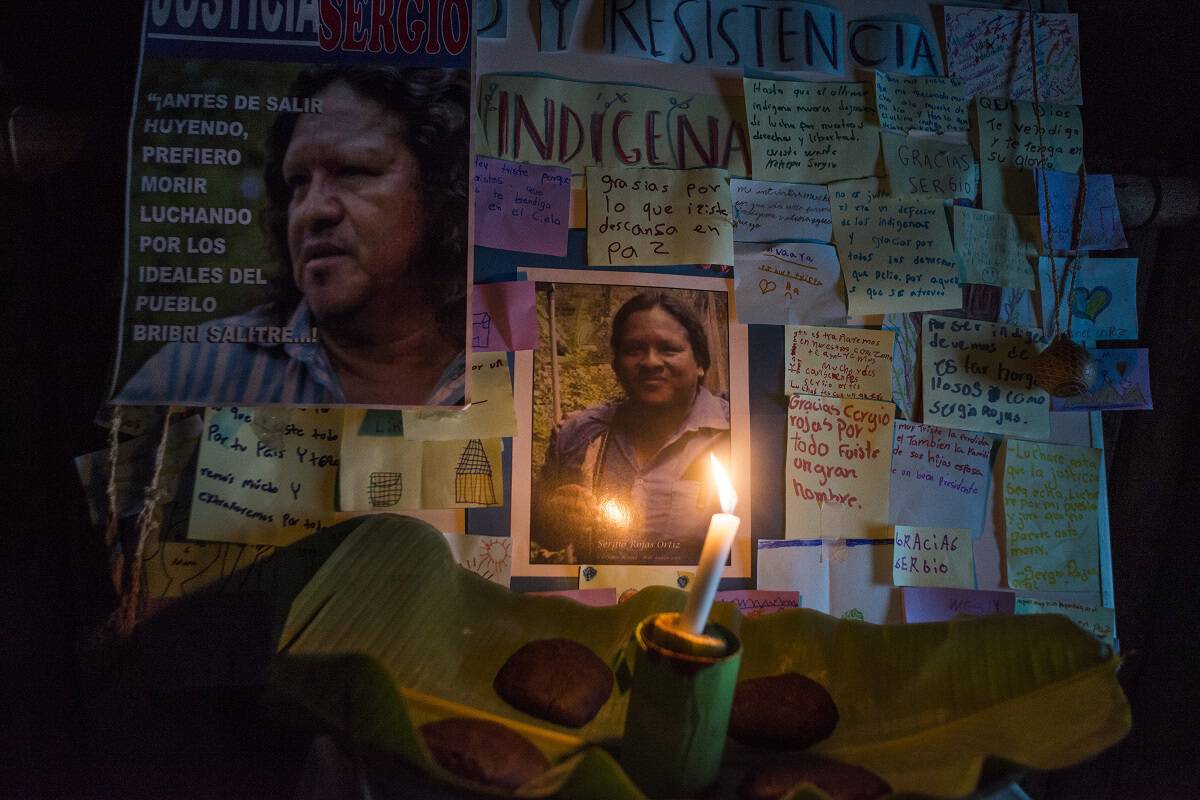

Rojas was murdered on March 22, 2019 after years of leading a movement to recover land belonging to indigenous people in the southwestern Costa Rican town of Salitre.

Though the 1977 Costa Rican Indigenous Law reserved land to the eight indigenous peoples, numbering around 114,000, much of the land is now occupied by non-indigenous — either by long-time owners who were never compensated for the land by the government or by settlers who have since squatted on the land.

Indigenous leaders are hopeful that the crime will soon be solved despite the worries of continued violence against indigenous “recoverers” who have been subject to aggression from the non-indigenous settlers.

“Of course we are nervous, but we are also confident in the Costa Rican State, which is giving us a lot of cooperation,” said Felipe Figueroa, 55, secretary of the Ditso Iriria Ajkinuk Wakpa Council of Salitre, which is seeking to recover land in indigenous territories that is in the hands of non-indigenous people.

Starting in 2010, Rojas, who was 59 at the time of his death, began leading an effort by the Bribrí community to reclaim the land for the rightful indigenous owners.

After his death, Rojas’s work was recognized by dozens of Bribrí members in a ceremony commemorating his life.

“He was a great leader and a great defender of his people,” said Marina López, one of the organizers, at the time. “Even if he was hungry, with no money, he was on the forefront of the fight.”

When Rojas began his campaign to retake the land, he presented a challenge to the status quo by becoming a figure of some renown in a community notably lacking in effective leaders, said University of Costa Rica anthropologist Marcos Guevara.

“Non-indigenous people do not want a strong leader who has a purpose of recovering land,” Guevara said at the time. “Rojas poses a special danger because he can inspire indigenous members in other parts of the country to demand their rights for their lands.”

And Rojas was a polarizing figure even within indigenous communities.

Rojas’s determination to restore indigenous Bribrí institutions in the territory alienated him from other peoples.

The Bribrí are matrilineal societies, meaning anyone born to a Bribrí woman is considered to be Bribrí, while someone born to a non-Bribrí indigenous woman is not considered “of clan.”

To some indigenous detractors, Rojas discriminated against the Cabécars, a distinct people closely related to the Bribrí.

One Cabécar farmer, Sary Sosa, told the daily La Nación last year that she felt threatened by Rojas.

She characterized the situation as a division between the “indigenous who go with Sergio Rojas and the indigenous who don’t go with Sergio Rojas.”

“I don’t go with anything that he says,” Sosa said. “I don’t respect him as a leader. I don’t accept him, I don’t want him, I would even like them to take him out of the territory.”

Vanessa Jimenez, an attorney for the Forest People’s Programme, a non-governmental organization that gives legal aid to indigenous groups, said that the differences between the Bribrí and Cabecar should be handled as an internal conflict-resolution problem and not by the state.

Indeed, Jimenez says, Costa Rica’s stellar human rights record doesn’t extend to its neglect of indigenous groups — who, the government acknowledges, hold the clear title to the land they are claiming.

One example of Costa Rica’s varying approach to its indigenous groups is the large copper field that spans the Panamanian border on land largely occupied by indigenous peoples.

The Panamanian government has allowed copper companies to exploit large mines over the objections of the Ngäbe-Buglé people.

On the Costa Rican side, copper companies sought extensive concessions in the 1990s — but under Costa Rican law, the country’s Legislative Assembly had to approve those concessions.

After protracted delays by the Legislative Assembly to even take up the concessions in committee, the copper companies rescinded their requests to the Costa Rican land.

On another front, the Costa Rica’s Ministry of Environment employs indigenous people in national parks, and the Ministry of Foreign Relations named the Bribrí attorney Guillermo Rodriguez Romero as ambassador to Bolivia in 2018.

Still, after the murder of Rojas, the struggle to regain indigenous land will continue, said National Distance University anthropologist Amilcar Castañeda.

“There is a popular saying, ‘The honeycomb has been touched, and the bees are angry.’ There is much consternation throughout the country. If the objective was to terrorize the indigenous population, and particularly the land recoveries, [to] stop the fight for land, I believe that the shot backfired,” Castañeda said. “The people have unified and renewed their commitment to continue and deepen with the struggles for land and indigenous rights.”

Such was the case of the Kalpeña farm which was “recovered” on Nov. 1, 2019. The Bribrí Figueroa Ortiz family repossessed the 60 acres of land held since the 1980s by Edwin Guevara Mora, a non-indigenous person, “who has illegally occupied several farms within this territory and who has also been involved in various acts of violence against the Bribrí people of Salitre,” according to the indigenous activist group, Ditsö Iriria Ajkönuk Wakpa Council of Salitre.

“The Figueroa Ortiz family, headed by Magdalena Figueroa Morales, are descendants of the original owners of the land. Known as the land of the leaf-cutter ants (zompopas), … [it] was previously inhabited and worked by the Bribrí Ramón Figueroa Figueroa and his descendants and family members,” the rights group said.

Rojas’s legacy will certainly continue to animate indigenous peoples in Costa Rica.

In 2016, Rojas spent seven months in “preventive detention” after he could not account for funds meant for a reforestation project in his community — where he was the head of the community development agency.

In his defense, Guevara said that many communities have seen fiscal disorder in the nationwide reforestation program and that Rojas’s lifestyle did not show outward signs of wealth from ill-gotten gains.

“He always said he was innocent, and one of his attorneys, Ruben Chacon, whom I have known for a long time, also believed in his innocence,” Guevara said. “He did not have a luxurious house, more like a humble home, nothing that would permit you to say that he had profited with a lot of money. Nor did he have objects of great value and, as far as I know, no bank accounts full of money.”

The Forest Peoples Programme attorney Vanessa Jimenez said that she is hopeful that international pressure can be brought to bear Rojas’s murder, though she said Costa Rica is shielded somewhat from criticism because of its otherwise stellar human rights reputation.

“When we fundraise, people first say, ‘There are indigenous in Costa Rica?,’ ” Jimenez said.

“Then they say, ‘What human rights problem?'”

This story was updated to correct indigenous names and to accurately reflect how much land in Costa Rica is occupied by non-indigenous people.