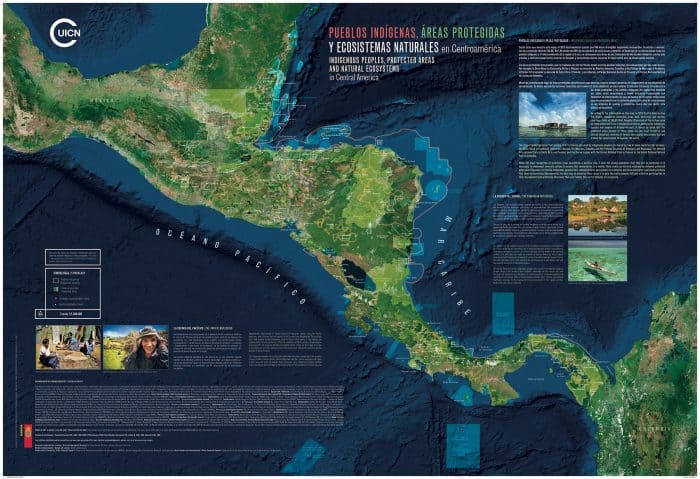

Indigenous communities may play a crucial role in the preservation of Central America’s forests, according to a new map produced by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The map, “Indigenous Peoples, Protected Areas and Natural Ecosystems in Central America,” is the most comprehensive map of its kind ever produced for the region.

In addition to traditional mapping methods, researchers used unpublished information gathered from interviews of more than 3,500 indigenous people. The new information allowed cartographers to accurately position indigenous communities on the map and also provide details on topography and bodies of water that could not be detected in satellite surveys.

The resulting map shows that approximately 51 percent of Central America’s current forest cover is either inside or adjacent to indigenous territory.

“You cannot talk about conservation without speaking of indigenous peoples and their role as the guardians of our most delicate lands and waters,” said Grethel Aguilar, Regional Director of the IUCN Office for Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, which is based in San José.

“This map shows that where indigenous people live, you will find the best preserved natural resources. They depend on those natural resources to survive, and the rest of society depends on their role in safeguarding those resources for the well-being of us all.”

The map adds to a growing body of information that sheds light on the importance of indigenous communities in conservation in Latin America. A 2014 study showed that the presence of indigenous communities significantly lowers deforestation caused by drug traffickers operating illegally in remote parts of Central America, and country-specific programs have begun to involve indigenous people in the policing of protected areas.

Along with highlighting the groups’ importance, the map has already begun helping indigenous communities assert their rights over their territories. In Western Panama, the Ngäbe people were able to use details from the map to demonstrate to the government that construction of the Barro Blanco dam would flood a significant part of their territory. Government officials had previously insisted that the indigenous land would be unaffected by the project.

In Guatemala, a Maya community is now using the map’s data to assert its rights over ancestral lands that leaders say was illegally expropriated by palm oil companies. Ramiro Batzin, Sotz’il Association representative and member of the Central American Indigenous Council (CICA) that worked on the map, hopes the map will prove useful to other indigenous communities engaged in similar battles throughout Mesoamerica.

“The map is an instrument that allows indigenous peoples to advance the recognition, respect and promotion of their rights”, Batzin said. “It will serve us as a valuable tool for advocating for a greater role for indigenous peoples in natural resource conservation, and for opening up a dialogue with states and conservation organizations.”

While the map shows the capabilities indigenous people have in conserving forest within and near their territories, it also indicates a disturbingly high rate of deforestation in other areas.

Comparing the new map to an approximate map from 1950, researchers noted that the region has lost as much as two-thirds of its original forests. Though an initial development boom in the wake of WWII caused the first wave of deforestation, researchers note the expansion of extractive industries and agro-businesses as well as illegal expansion into protected territories within the region.

The outlook of the region’s forests may seem grim, but the trajectory can be reversed. The map’s accompanying report highlights the successes of Costa Rica’s reforestation policies, which enabled the country to increase forest cover from 21 percent to 52.4 percent in a manner of decades. The most extensive tract of original forest in Costa Rica lies within the indigenous territory of the Bribri and Cabécar.