WASHINGTON, D.C. – From salmon farming in southern Chile to shipbuilding in landlocked Paraguay, Japanese companies are pursuing investments throughout Latin America – with an eye toward future opportunities under the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

In late February, Inter-American Dialogue organized a panel in Washington that analyzed how Japan’s ties with the region have relationship rebounded since the 1980s and 1990s. The event coincided with the release of a 16-page report, and builds on a September 2015 gathering co-hosted by the Dialogue and the Japan Association of Latin America and the Caribbean (JALAC), a Tokyo-based organization founded in 1958 to promote Japanese public and private-sector engagement in the Americas.

Although the current focus is on China, panelists said there’s been a reawakening of Japanese interest throughout the region, underscored by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s summer 2014 tour of Mexico, Trinidad, Colombia, Chile and Brazil – the first Latin America visit by a Japanese head of state in a decade.

“Japan’s approach to trade liberalization in LAC is unique, in that it prefers to negotiate economic partnership agreements [EPAs], which have a wider scope than free-trade agreements,” said Margaret Myers, director of Inter-American Dialogue’s China and Latin America Program and co-author of the report, along with Mikio Kuwayama.

“It’ll be the first East Asian country to have EPAs with all four Pacific Alliance members [Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru],” said Myers. “Japan’s engagement with Latin America is also highly diversified, with FDI flows even distributed among primary goods, services and manufacturing.”

In 2014, Japan’s total trade with the region came to $64 billion, more than South Korea’s $54 billion, but only a fourth of China’s $254 billion. Three countries – Mexico, Brazil and Chile – accounted for 75 percent of total Latin American exports to Japan between 2011 and 2014, led by copper, iron, meat, coffee, fish, aluminum, pulp and oil.

Yet as the report points out, “although China’s trade with the region far exceeds Japan’s, in general Japanese exports are less threatening to the region’s manufacturers than Chinese goods. Because Japan’s export basket consists primarily of high-tech, capital-intensive products, they rarely compete with those of Latin America, whether in domestic or third markets.”

From 2009 to 2011, Japan was the top foreign donor to Costa Rica, Panama, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and a few smaller Caribbean islands. Meanwhile, loans and equity commitments by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) exceeded $10 billion in fiscal 2012, surpassing World Bank support of $6.6 billion that year and nearing the $11.4 billion pledged by the IDB.

By comparison, combined lending to Latin America and the Caribbean by the China Development Bank and China Eximbank was about $8 billion in fiscal 2012. Chinese policy bank finance to the region has averaged $11 billion a year since 2005, though in 2015 it reached $29 billion.

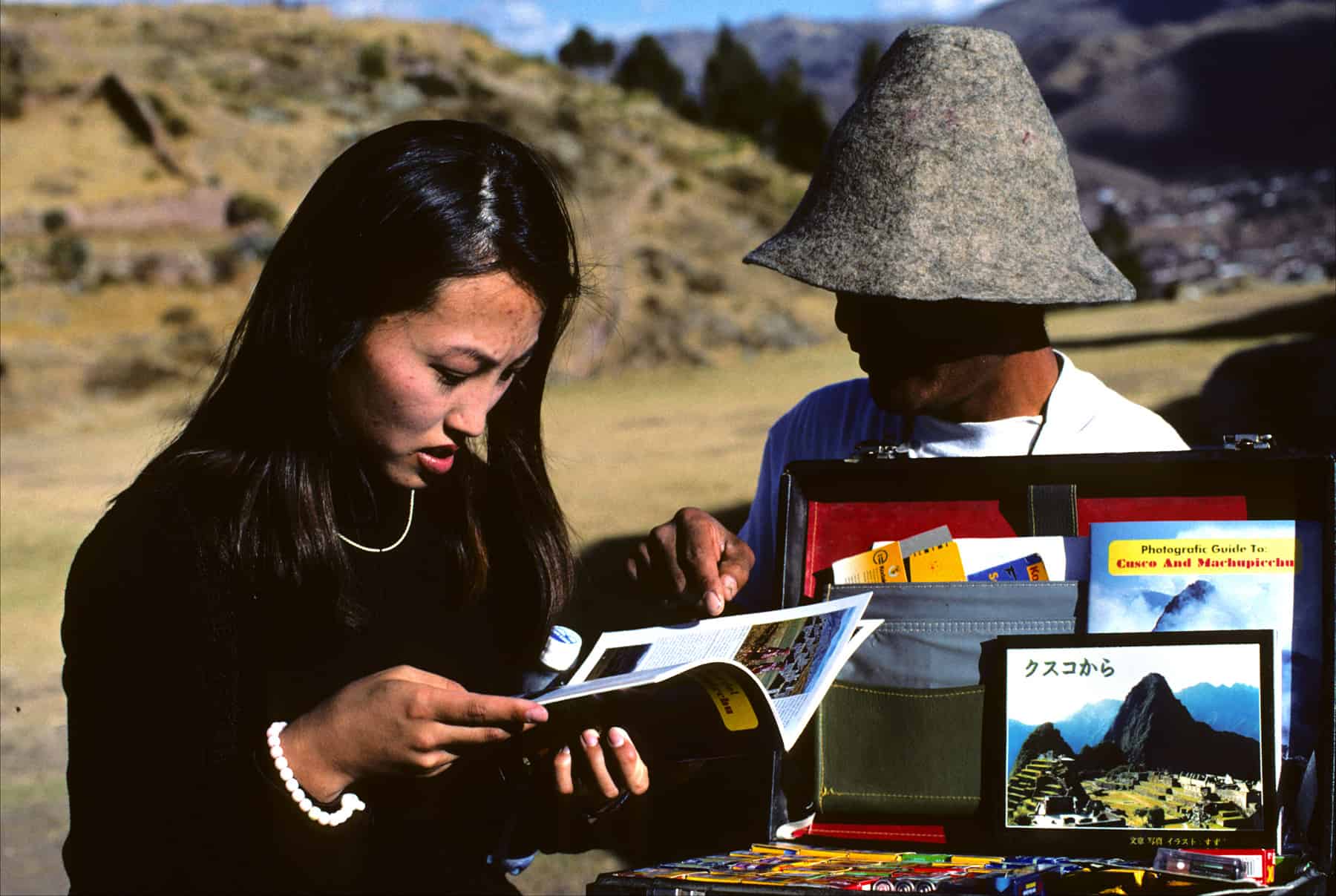

Norihide Tsutsumi, CEO of Mitsubishi Peru, said more than 800 Japanese entities have offices throughout Latin America. If one includes the nikkei community of ethnic Japanese who permanently relocated overseas and their descendants, that number rises to 7,000 entities. Some 1.8 million Japanese descendants live in Latin America and the Caribbean, having migrated there over the course of a century; Brazil is home to 1.6 million of them, and Peru to another 100,000.

Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori and his daughter Keiko Fujimori – the front-runner in Peru’s 2015 presidential race – are among Latin America’s best-known nikkei. Said Myers: “These communities support and deepen economic linkages, and their contributions in these countries have led to a generally positive perception of Japan in Latin America.”

Tsutsumi said Mitsubishi was one of Japan’s early pioneers in the region, coming to Mexico in 1955 and quickly expanding to Brazil, Argentina and the rest of South America. At the moment, Mitsubishi has 15 offices in 12 countries; the 63 entities it has invested in employ thousands of Latin Americans.

Yet the Japanese economy is struggling, with GDP expected to grow only 1.7 percent in real terms this year, and Latin America is doing even worse. The IMF pegs 2016 regional growth at below 1 percent, and the World Bank says it won’t grow at all.

“Due to decreasing commodity prices, the slowdown in China’s economy, the number of new companies has slowed down,” said Tsutsumi, who came from Lima for the event. “On the other hand, the appetite to enter the Latin American market by Japanese companies is still very strong. I see many companies coming to Peru and elsewhere to investigate the timing and place to possibly set up new offices in Latin American countries – especially on the Pacific side.”

He added: “Our origin is trade, and trading is still the basis of our business, but our total risk exposure to Latin America is over $15 billion, and profit from our investment activities is now larger than traditional trade. Mitsubishi is very confident of the region’s growth potential.”

Yet Tsutsumi noted that at present, Japan has double-taxation treaties only with Mexico, Brazil and Chile.

“Paying taxes is one of our basic responsibilities. However, double taxation is a fatal factor for making investments, and we sometimes need to invest through third companies in order to avoid that,” he said. Such costs are actually paid by the project itself and also any increase in tax will significantly affect the project’s feasibility.”

Another problem is corruption.

Kazushige Taniguchi, an adviser to the IDB, said the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the World Bank share the same kind of blacklists.

“If companies are engaged in corruption, they are taken off the approved list,” he said. “But that does not mean that if one company or minister might get involved in corrupt practices, that the whole project should be gone.”

The current Petrobras scandal shaking Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff has badly rattled Japanese and all foreign investment in Brazil, said Monica de Bolle, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“Brazil and Japan have had a long-standing relationship. The National Confederation of Industry and the Japan Business Federation put together a document that looks toward an economic agreement between Brazil and Japan,” she said, “but people have no idea what’s going to come out of these investigations and what’s likely to happen. There’s a lot of uncertainty hanging over the country at this moment.”