Eleven days of bruising international diplomacy in the French capital have failed to resolve a host of decades-long arguments between rich and poor nations over how to cut greenhouse gas emissions that cause global warming. But, with feuding negotiators from 195 nations heading into a second night of talks, Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius submitted a new draft of the planned accord and said it was time to take the “decisive step.”

“We are extremely close to the finish line,” Fabius, who is the president of the talks, told the negotiators. “It is time to come to an agreement. What is important now is to seek landing zones and compromise.”

World leaders have described the Paris talks as the last chance to avert disastrous climate change: increasingly severe drought, floods and storms, as well as rising seas that engulf islands and populated coastal regions.

The planned accord would seek to revolutionize the world’s energy system by cutting back or potentially eliminating the use of greenhouse gas culprits coal, oil and gas — replacing them with renewables such as solar.

Blame game

U.N. efforts dating back to the 1990s have failed to reach such an agreement. Developing nations insist the United States and other established economic powerhouses must shoulder the lion’s share of responsibility as they have emitted most of the greenhouse gases since the Industrial Revolution.

But rich nations say emerging giants must also do more, arguing that developing countries now account for most of today’s emissions and thus will be largely responsible for future warming.

Related: US inflames debate on climate finance with plan for UN talks

Those fault lines are continuing to keep both sides from reaching an agreement.

Still, delegates said the mood in Paris remained relatively positive, and the finger-pointing and back-biting of past climate talks were so far absent.

In an effort break the deadlock and ramp up pressure on negotiators to compromise, Fabius launched non-stop talks on Wednesday night. They were due to run again through the night on Thursday, with Fabius expressing hope of still being able to meet a Friday deadline for sealing the accord.

But others were less sure, with senior Chinese climate envoy Li Junfeng telling reporters earlier he thought a Saturday finish was the best-case scenario.

As part of a carefully coordinated U.S. diplomatic push for a deal, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry met Thursday with Indian Environment Minister Prakash Javadekar. India is a key player in Paris because it has huge coal resources that it wants to burn to power its economic development.

Deal-busters

One of the biggest potential deal-busters remaining is over money. Rich countries promised six years ago in Copenhagen to muster $100 billion a year from 2020 to help developing nations make the costly shift to clean energy, and to cope with the impact of global warming.

But how the pledged funds will be raised still remains unclear — and developing countries are pushing for a promise to ramp up the money in the future.

Another flashpoint issue is how to compensate developing nations that will be worst hit by climate change but are least to blame for it. The developing nations are demanding “loss and damage” provisions, which the United States is particularly wary of as it fears they could make U.S. companies vulnerable to legal challenges for compensation.

Most nations submitted to the U.N. before Paris their voluntary plans to curb greenhouse gas emissions from 2020, a process that was widely hailed as an important platform for success.

Costa Rica’s climate pledge: 5 things to know

But scientists say that, even if the cuts were fulfilled, they would still put Earth on track for warming of at least 2.7 C.

Negotiators remain divided in Paris over when and how often to review national plans so that they can be “scaled up” with pledges for deeper emissions cuts. Climate experts hope clean energy sources will eventually be cheaper than fossil fuels.

Another battleground is what cap on global warming to enshrine in the accord, set to take effect in 2020.

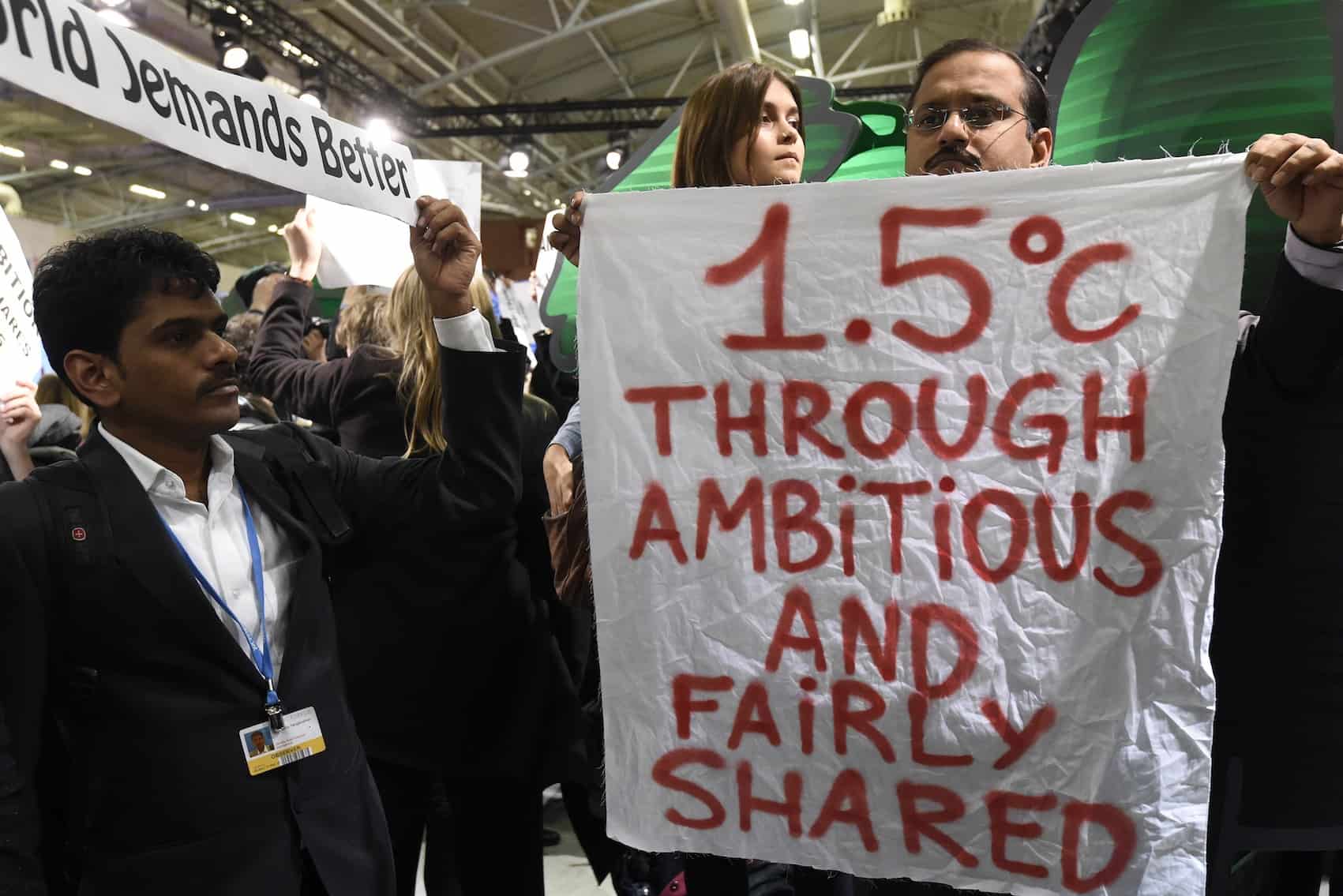

Many nations vulnerable to climate change want to limit warming to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.5 degrees Fahrenheit) compared with pre-Industrial Revolution levels. However several big polluters, such as China and India, prefer a ceiling of 2 C, which would allow them to burn fossil fuels for longer.

There was growing confidence within the vulnerable-nation bloc that they would win their high-profile campaign, and secure a reference to the 1.5 C target in the key “purpose” section of the planned accord. This was partly due to the emergence of an informal new lobby group that emerged this week in Paris dubbed the “High Ambition Coalition,” which includes the United States, the European Union and many vulnerable nations.

The group does not negotiate as a bloc, but is seen as having influenced the talks by heavily promoting “ambitious” benchmarks in the planned accord, such as a 1.5 C reference.

See also: Costa Rica honored at Paris climate talks with message on Eiffel Tower