SANTO DOMINGO LOS OCOTES, Guatemala – On the eve of Guatemala’s general elections, the smell of acrid smoke filled the air in the village of Santo Domingo Los Ocotes, located in the department of El Progreso, 77 kilometers east of Guatemala City. Angry villagers, many of them carrying firearms, set up an improvised barricade blocking the main entrance to the village. There they burned tires to deter residents from neighboring towns from being shuttled in on Election Day, on Sunday, in exchange for money or a meal, a practice known as acarreo that is commonplace in a country where 53.7 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.

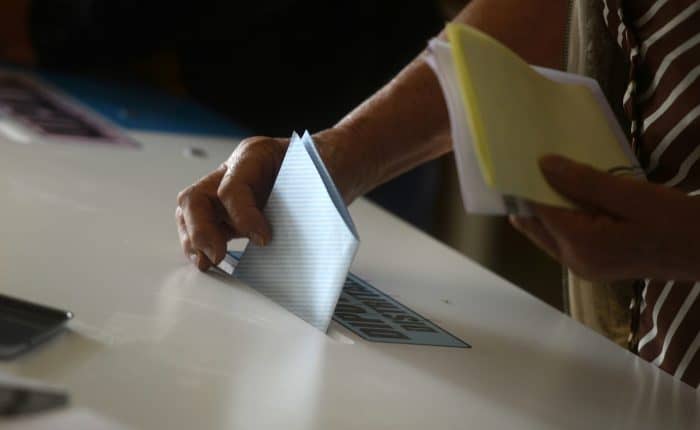

Guatemalans headed to the polls Sunday to elect a new president, along with members of the 158-seat legislature and 338 mayors, just days after the country’s president was jailed on corruption charges, the AFP reported.

See: PHOTOS: A look back at how Guatemalan citizens demanded justice – and won

Santo Domingo Los Ocotes is a small, dusty and impoverished village where gang violence has been on the increase in recent years. On Monday, the atmosphere remained tense as riot police were sent in to prevent outbreaks of violence.

Rumors that people from other towns would be massively herded in to vote, mainly by the Líder party, also spread like wildfire in El Progreso’s capital, Guastatoya, and the small village of Santa Rita, located between Guastatoya and the eastern department of Jalapa.

In Sanarate, another town in El Progreso, sympathizers from the ruling Patriot Party and the Nationalist Change Union started a brawl after the polling station closed.

Outbreaks of violence were also reported in various parts of the country after polling stations closed and the votes were being counted.

In the town of Pueblo Nueva Viñas, in the eastern department of Santa Rosa, an angry mob stormed the town’s three polling stations to prevent a vote count. Residents there are opposed to a win by Líder candidate Ervin Zamora.

Other incidents were reported in the departments of Jutiapa and Suchitepéquez.

The most common complaint throughout the country was voter herding, or acarreo.

One of the most serious incidents recorded by the Demos observation mission occurred in the municipality of Amatitlán, near Guatemala City, where Líder allegedly shuttled 90 buses of paid supporters – some 3,600 people – all the way to the department of Alta Verapaz, in northern Guatemala, approximately 245 kilometers away.

Meanwhile, in the municipality of Salcajá, in the highland department of Quetzaltenango, Líder sympathizers accused the mayor, who was elected in 2011 by the Creo party and is seeking a second term in office, of attempting to bring in people from neighboring towns.

“Be warned that if you’re coming from other municipalities to vote here you’ll be detained [per] Electoral Tribunal Agreement 1-2015,” read three large banners placed in the main entrance points to the town.

“The banners sought to intimidate people by alluding to the decree issued by the Supreme Elections Tribunal in January this year, preventing people from changing their registered address from that date onwards in order to prevent voter herding. The decree exists but doesn’t state that anyone will get arrested,” Rumualdo Quijabaj, president of the Salcajá voting center, told The Tico Times.

Some voters complained that in their zeal to prevent voter herding, members of various parties interrogated and harassed them in an attempt to ascertain whether they really lived in that town.

On some occasions, parties went to great lengths to mobilize supporters. In the village of San Lorenzo El Cubo, in the department of Sacatepéquez, locals reported that several parties drew up lists of voters who would be shuttled to the polls and marked their houses with an “X” so that they could be easily located.

Líder: the main culprit

“Voter herding is nothing new; it has become an established practice,” Edgar Pereira, coordinator of the Demos observation mission in 52 municipalities, told The Tico Times. “On some occasions it has led to violence when people claim a certain candidate won despite the fact that nobody voted for him or her, thanks to the votes cast by people who don’t even live there.”

This year, Pereira said, electoral authorities made efforts to prevent voter herding by establishing a deadline for people to change their registered address. But it was already too late. He added that in small, rural towns and villages it is relatively easy to spot acarreados, because they don’t speak the local language or wear the local indigenous clothing. However, in large suburban municipalities such as Chinautla, in the outskirts of Guatemala City, it is far more difficult to detect those who have been paid to vote.

This year, Líder was the party most commonly accused of voter herding. A week before the elections, Líder presidential candidate Manuel Baldizón caused widespread anger after an audio recording was leaked to the media in which he urged mayoral candidates to mortgage their homes and vehicles to shuttle as many poor voters as possible to the polls.

“We’re going to use votes to kick their asses,” he said, referring to demonstrators who have rejected him due to his party’s alleged involvement in a huge money laundering scandal.

According to Mirador Electoral, another observation mission, most cases of voter herding were reported in the departments of Guatemala, Escuintla (south) and San Marcos (north).

In San Pedro Jocopilas, in the highland department of Quiché, Líder was accused of handing out cash payments to voters, particularly elderly women, and of standing next to them while they voted to ensure they chose the “correct” party. Líder’s spokesperson, Fridel de León, was unavailable for comment on the allegations of voter shuttling and vote-buying in various parts of the country.

Electoral observers also reported a number of technical problems across the country such as voting centers where people were allowed to use their cellphones despite the fact that this is forbidden, and a shortage of staff members who could speak local Mayan languages.

Said Pereira: “The mestizo population doesn’t regard this as important, but it’s a serious limitation in a country where many people don’t speak Spanish.”