See also: Costa Ricans react to FIFA scandal like every other scandal: with memes

International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach on Thursday told the functionaries of FIFA, football’s governing body, to clean up their act as the IOC did 15 years ago. His advice might have been more credible had FIFA President Joseph Blatter, himself an IOC member, not just introduced Bach as “the Boss.” International sports organizations have too much arbitrary power for their attempts at self-improvement to be effective.

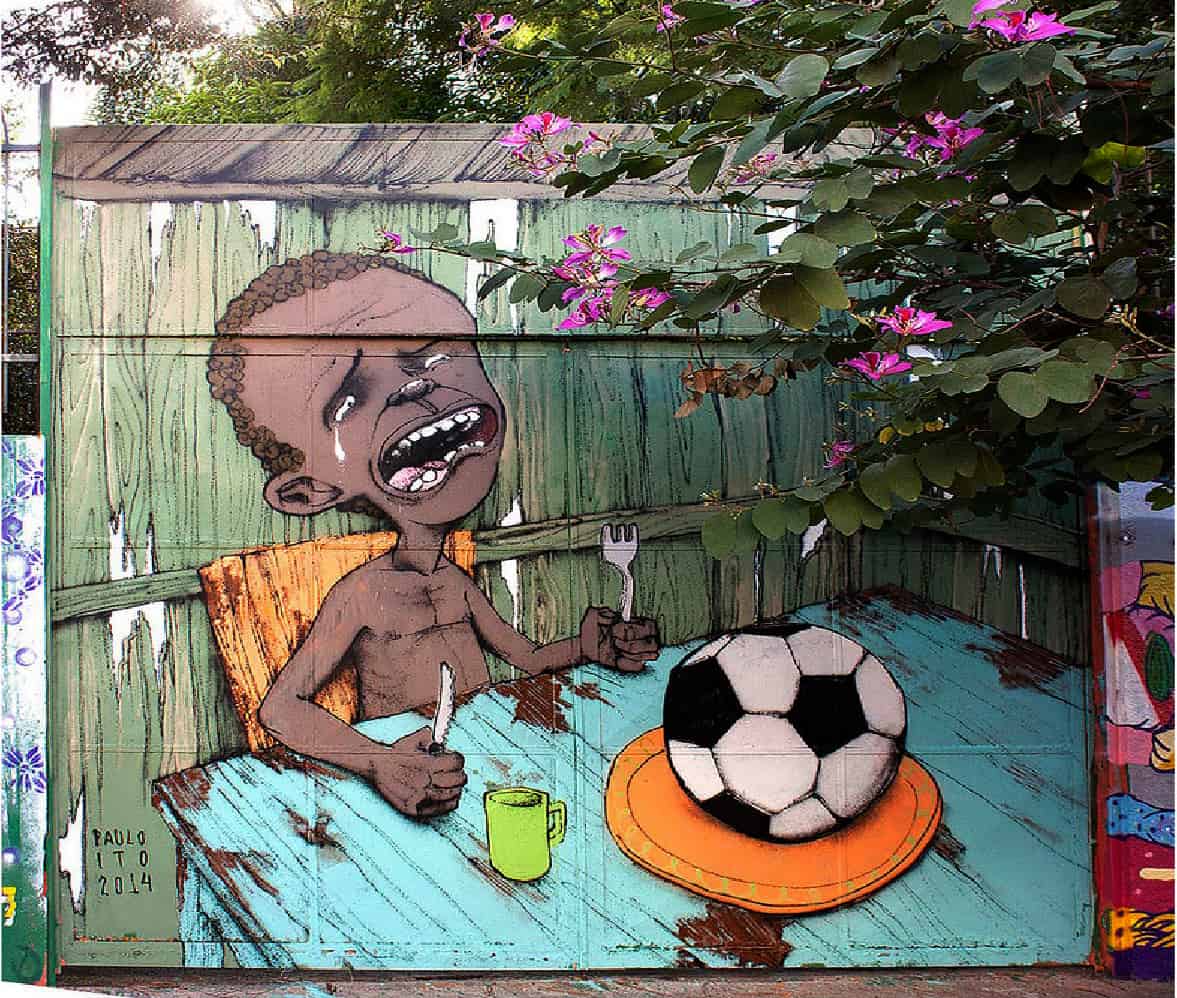

The mega-events that FIFA and the IOC stage — the World Cups and the Olympics — are ideal vehicles for corruption. They are vanity projects for governments because they put a country and a city in the media spotlight, bring in crowds and guarantee politicians a grand legacy. In developing countries especially that leads officials to spare no expense. At all costs, they must avoid being seen as “third world.” Thus the preposterous price tags: $15 billion for the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, $40 billion for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, a whopping $51 billion for last year’s Winter Olympics in Sochi.

The truth has long been established that these mega-events bring their hosts little of lasting benefit, and that’s especially true of developing countries, whose opportunity costs of capital are higher, as a 2003 paper by Victor Matheson and Robert Baade showed. The researchers said:

“From an economic point of view, the cost of building a new stadium is not best described by the amount of money needed to build the facility but rather the value to society from the same amount of capital spent on the next best public project. Nigeria’s government recently spent $330 million on a new national soccer stadium, more than the annual national government expenditures on health or education.”

It is in these countries, however, that politicians and officials feel especially royal and inclined to splurge on vanity projects — not just to build gigantic monuments to themselves in the shape of new stadiums, airports and roads but also to enrich themselves and their friends. Big infrastructure projects are ideal for rigged tenders and skimming, and there’s less chance that wrongdoing will surface. Nobody went to jail for the enormously inflated costs in Brazil, China or Russia. Corrupt practices do sometimes surface — mainly in countries with more transparent governance. This year’s $14 billion World Expo in Milan, for example, has seen officials and former legislators arrested and accused of bribery.

Given the opportunity for corruption, it’s no wonder IOC and FIFA officials are subjected to huge temptations. The U.S. indictment of FIFA speaks of million-dollar bribes allegedly offered and paid by the Moroccan and South African bidders to secure votes from FIFA executive committee members. Compared with the subsequent outlays for sports infrastructure, that’s small change. But for the FIFA executives, it’s enough money to secure the futures of their children’s children.

The IOC’s big corruption scandal played out in the late 1990s, when the budgets — and the bribes — were much smaller. Like the current FIFA scandal, it emerged in the U.S. The organizers of the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics tempted IOC members with gifts, expensive trips and, for a member’s daughter, tuition at a U.S. university. The fallout was relatively severe: Ten IOC members were expelled or resigned in disgrace. The organization set up two commissions to reform itself so that future bribery would be ruled out. Their recommendations weren’t particularly suited to that purpose, however. The only strong anti-corruption measure was a ban on IOC members’ trips to bidding cities.

Bach, a protege of Juan Antonio Samaranch, who was IOC president at the time of the scandal, headed up the organization in 2013 and almost immediately broached the idea of repealing that rule: “If you want to corrupt somebody, he doesn’t have to come to you,” he argued. The no-visit rule has remained on the books, though it’s difficult to say whether it’s been particularly useful. The selection of subtropical Sochi, almost devoid of winter sports infrastructure, as the host city for the 2014 Games was as questionable as Qatar’s winning the 2022 World Cup. The organization’s DNA has remained the same, and the temptations have only increased.

No doubt Blatter, who has promised a cleanup to restore FIFA’s reputation, would like to engage in the same kind of window-dressing: Set up a whistle-blower hotline, draw up a procedure for bidders’ access to FIFA functionaries, pass some symbolic measures like the visit ban and declare the job done. He might even accept more or less transparent bidding for TV rights, IOC-style, rather than continue to hand them out without a tender.

The core problem would remain: Politicians seeking glory would still be willing to buy votes from FIFA and IOC members.

An obvious way around this would be to auction the host status for major sports events. The prize would go to the highest bidder, earning more money for football or Olympic sports than for corrupt functionaries.

To ensure a regular rotation of cities, previous successful bidders would have to wait 20 years before they could participate again. And richer countries wouldn’t necessarily always win, because poorer ones could pool their resources to compete.

Blatter and Bach are not the right people to make this kind of radical change. And the hierarchies that have placed them at the top are too steeped in old-style politics and corruption to demand it. It will probably take more scandals and more indictments for the international organizations to realize that business as usual is no longer possible.

Leonid Bershidsky, a Bloomberg View contributor, is a Berlin-based writer.

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit http://www.bloomberg.com/view

© 2015, Bloomberg News