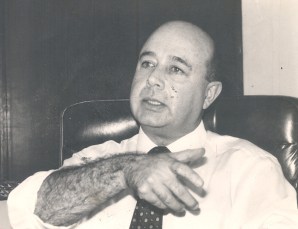

Álvaro Ugalde, who along with Mario Boza is considered a father of Costa Rica’s world-famous national park system, died Sunday of a heart attack in his home in Heredia, east of San José, a day short of his 69th birthday.

Ugalde, though retired from public service, remained active in the effort to preserve Costa Rica’s 26 national parks, focusing particular attention on Rincón de la Vieja in the northwestern province of Guanacaste, where the Costa Rican Electricity Institute (ICE) is pushing plans to exploit geothermal energy, and Corcovado National Park on the Osa Peninsula in southwestern Costa Rica, where gold panners and nearby development threaten the biological integrity of the park.

Ugalde, a biologist by training, continued to work with local communities surrounding national parks to teach them the benefits of preserving the land for future generations.

Ugalde told the daily La Nación that Corcovado was his favorite national park, and he worried that if the government failed to protect the “jewel of the park system,” Costa Rica’s entire national park system could be at risk.

Ugalde also worried that sequestering land inside Rincón de la Vieja as proposed by ICE would set a precedent of removing land from the national park system that would leave any other national park exposed.

“If we can’t save Corcovado and Rincón de la Vieja the whole park system could go,” Ugalde said.

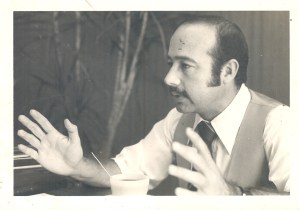

In the 1970s, Ugalde and Boza began pushing the idea of converting watersheds already protected by ICE to preserve the country’s hydroelectric capacity into national parks. The duo’s idea found powerful patrons in the persons of President Daniel Oduber and former First Lady Karen Olsen, the wife of three-time head of state José “Pepe” Figueres. The first national park, Poás Volcano, was founded in 1970.

From the beginning, Ugalde and Boza were confronted with problems such as squatters, gold panners and hunting inside the parks.

Also, many of the parks at the beginning were “paper parks,” existing only in theory, as they were private property with no national park service presence.

Ugalde worked tirelessly to reverse that trend, inviting wealthy individuals and foundations to see for themselves the wonders of Costa Rica’s wild areas, which netted millions of dollars in donations to buy up in-holdings in the parks.

But the idea of national parks was a novel one for Costa Ricans, and Ugalde and Boza had trouble selling it to locals, who saw little benefit, and members of the influential business sector, many of whom saw the national parks as unaffordable luxuries for the third world country.

By the early 1980s, Ugalde warned that Costa Rica’s preserved areas remained at risk, saying that because of the high level of deforestation at the time, Costa Rica would be lucky to preserve the national parks as “islands” in a sea of denuded landscape.

All that changed in 1987, however, when then-President Óscar Arias won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to bring peace to the warring factions in Central America.

Arias “put Costa Rica on the map,” attracting millions of visitors and sparking a tourism boom that made tourism the No. 1 source of foreign exchange income for the country.

The value of the parks as a magnet for tourists became apparent to the point where conservationists are attempting to carry out their vision of connecting the parks by “corridors” of protected areas that would guarantee the preservation of gene pools for the many species endemic to Costa Rica.

Now, a total of 166 protected areas, both public and private, protect Costa Rica’s natural resources.

Still, to the end of his life, Ugalde said that work remains to guarantee the preservation of the country’s national parks, especially Corcovado, where development pressures and gold panners put it, in the words of Ugalde, “in danger of extinction.”

Ugalde said he believed that local communities surrounding national parks still don’t see the benefits of preserving the parks, presenting an enduring challenge to their protection.

“If I had hair,” said the bald Ugalde, “I would pull it out for building the parks from the top down, not the bottom up.”