After awhile, every expat gets the same suggestion: You should write a book! Friends exclaim this revelation over wine. Mothers yell it through the telephone. Fishing buddies and book club friends all say the same thing, excitedly, as if nobody has ever thought of this before. Your life is so interesting! You have so many stories! You should write all this down before it’s gone forever!

Most of these people should not write books. This fact cannot be overstated. Most expats should keep a detailed journal and then bequeath it to their children, who might find it rich with meaning. Widespread printing should be left to prodigies and professionals, not just anybody with a word processor. But the memoir bug bites hard, and thousands of terrible autobiographies have been published and forgotten because thousands of expats have no idea how to write.

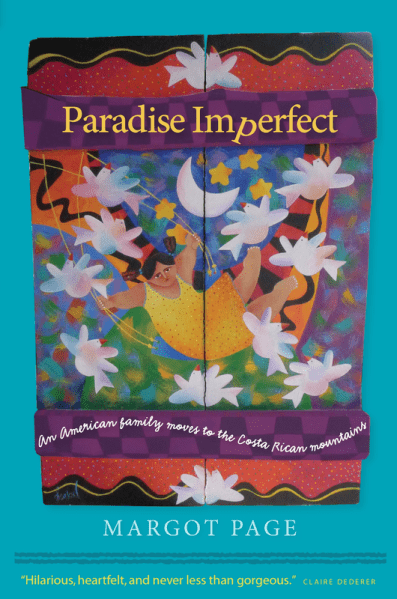

Margot Page is not one of those. A native of Seattle, Washington, Page worked for many years for Microsoft. She is married to a decent-sounding guy named Anthony, and together they’re raising three kids. When the hectic soccer-mom lifestyle became unbearable, the Page family moved to the Costa Rican mountain town of Monteverde for a year of pura vida. Then, like clockwork, they returned to the U.S. and Page wrote a book about it.

Unlike so many would-be authors, Page can put words together. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee and has published in The New York Times. Her literary competence shows. Some sections in “Paradise Imperfect” are smart and eloquent, and she frames her story well. In the early chapters, Page sounds genuinely unhappy in her comfy, middle-class life.

The family’s decision to live in the Central American mountains, learn Spanish, and maintain a garden is healthy and cathartic. After 12 months, they have mixed emotions about returning to Seattle, but they have a new-found respect for home. Behold! A full narrative arc.

What’s more, when she’s feeling descriptive, Page excels. Here is a particularly lush sample:

On the downhill side of [the] pasture, I could just make out the variegated edge of the rain forest – a cool, wet tangle of passion flowers and strangler figs. Individual trees blurred to furry green foothills, unrolling toward the flatlands until they resolved, finally, into the sparkling blue band of the Gulf of Nicoya.

But there’s a problem: This passage is the fifth paragraph of the entire book, and Page doesn’t sustain this level of beautiful prose. Instead, Page starts to write her chapters like blogs – chatty, jokey and filled with pop culture references. Instead of describing what she experiences, she substitutes with snappy one-liners:

We are going Catholic now. This was new to me, and I was only the tiniest bit disappointed that my new spiritual home wasn’t more ornate; I had thought the Catholics were all about the flying buttresses and the big rose windows. (When it comes to understanding Catholicism, I am deeply indebted to the novels of Dan Brown).

It’s wry, yes, but not ha-ha funny, and Page never describes what her church actually looks like. The book is rife with missed opportunities, where she decides to tell us her opinions instead of vividly illustrating her new world. The family’s visit to Nicaragua is presented first as a joke (maybe they’ll turn into Communists!) and then as one long guilt trip, because Nicaragua is so poor and full of stray dogs and flies. Their Tico neighbors are nondescript and one-dimensional. If you substituted “Montana” for “Costa Rica,” you’d probably believe the Pages moved to Butte.

Then again, such introverted writing is consistent with her character: Page describes herself as a high-strung alpha mom, the kind of demanding, paranoid, hypersensitive Gringa that most people avoid and Ticos particularly fear. Page berates her husband for being unmotivated, she anguishes over the health of her children, and she analyzes every one of her own decisions for signs of maternal failure. She obsesses over her children’s behavior in church. She scrutinizes a nearby vine (used as a rope swing) for potential lawsuits.

Page’s honesty is admirable, as is her self-deprecation, but it’s clear why she never seems to “belong” in Costa Rica. In a way, Page was never here, except in the most superficial sense. Her address was in Monteverde, but she spent most of that year in her own head, working things out.

There’s nothing wrong with this approach, of course. When Elizabeth Gilbert composed “Eat, Pray, Love,” she wrote in the same conversational style. The genre of restorative travel literature is big and best selling, and obviously people love to read about expats seeking “enlightenment” in faraway places. Helicopter parents will probably enjoy this book, because Page did what so many neurotic Gringo families dream of doing. It’s hard to vacation with kids, much less move to another country, much less justify a year of slowing down and rebuilding your family.

But like so many other travel memoirs, “Paradise Imperfect” is not really about Costa Rica. That, more than anything, is the imperfection.