SANTA ANA, San José — It’s a geographic mystery 455 years in the making, but most historians agree that the first Spanish settlement in Costa Rica’s Central Valley was built in what is today the canton of Santa Ana.

As you drive down the ultramodern, congested, strip malled road in Lindora today, it’s strange to think that Costa Rica’s latest, greatest address was also the first place Europeans decided to build a fort in the highlands of this unexplored region in the New World. Yet the collision of old and new is part of what makes Santa Ana unique, and it draws new explorers every day.

Columbus landed on the Caribbean coast in 1502, but the Spanish made few inroads into Costa Rica until 1561. In that year, a Spanish conquistador named Juan de Cavallón y Arboleda, who was a governor (alcalde mayor) of Nicaragua, undertook the pacification and settlement of the largely unexplored region to the south, known as Nuevo Cartago y Costa Rica.

In January 1561, Cavallón entered Costa Rica from Nicaragua, passing through Chomes, near modern Puntarenas. He marched inland, made camp, and sent out various raiding parties, including one that captured the powerful Chorotega chief Coyoche. The subjects of Coyoche then agreed to lead Cavallón farther inland.

The exact route taken by the conquistadors is impossible to reconstruct, but historians deduce from the topography and the need to avoid attack that they followed ridgelines that would have taken them through the current city of Santiago de Puriscal and into the Santa Ana Valley.

Somewhere here, the theory goes, Cavallón founded the first Spanish city in the Central Valley in 1561, named Castillo de Garcimuñoz after Cavallón’s birthplace in Spain. The location of this settlement is debated, with the most widely accepted theory placing it in the Santa Ana Valley, west of San José, while other research suggests it was farther east, in Desamparados.

Cavallón struggled to overcome resistance from native Huetar tribes, including one major group led by a chief named Garabito. Cavallón left Costa Rica in 1562 and died in Mexico in 1565. The settlement he founded was mostly abandoned after two years, in 1563, when inhabitants moved to the newly founded city of Cartago, Costa Rica’s first capital.

“The problem was that for the Spanish, the indigenous people were very important, because they used them as slaves for labor, and here in this valley there weren’t a lot of natives,” said Jorge Luis Acevedo Vargas, director of the Municipal School of Integrated Arts (EMAI) and author of a history called “Santa Ana: Sociocultural Resources.” “They had no labor, and so they moved the city two or three years later to the Guarco Valley (Cartago).”

The Santa Ana region was further colonized in the 17th century, when the Spanish crown ceded the land to Jerónimo de Retes, an official in Cartago. The name Santa Ana is first mentioned in the Protocols of Cartago in a letter dated Dec. 1, 1658, when the marriage of José de Alvarado to Petronilla de Retes, daughter of Jerónimo, brought part of the area into the couple’s possession.

Not long afterward, the land passed to Ana de Retes, Petronilla’s sister. The city was apparently named after St. Anne (Santa Ana), the mother of the Virgin Mary, possibly because Jerónimo felt a special affinity for the saint after whom he named one of his daughters.

In 1750, the Retes family sold a large piece of land — where a zoo called the Santa Ana Conservation Center stands today — to a doctor and priest named Juan de Pomar y Burgos. In 1765, this priest built a house, known as La Casona, that is still standing, as well as a chapel.

The property changed hands a couple of times until it came into the possession a priest named Ana Tiburcio Fernández Valverde. Fernández remodeled the old chapel and opened Santa Ana’s first church in 1850. It had a bell forged in London and a huge wooden door with a hatch through which confessions were heard.

The village of Santa Ana arose around this hacienda, although the “centro” later moved east around 1880, when the church that still stands there was completed. The Parish of Santa Ana became part of the Archdiocese of San José in 1885, gaining ecclesiastical if not political independence from its old master, Escazú.

Héctor Aguilar, an architect who owns the Casa de Antiguedades antique shop a block from the church, said the stones to build it were quarried in Piedades de Santa Ana, and a very unusual mortar was used.

“They used a chicken farm, because the mix they made to mortar the stones is called calicanto — it’s sand, egg whites and lime,” he said. They used the egg white, not the yolk, “because it’s sticky; they used it as an adhesive,” he said. “So they had a farm just to lay eggs and make the mix.”

Aguilar also recalled one of the most famous legends from this region, the story of the “Flooded Mine,” several versions of which are also recorded in Acevedo’s book.

“Some men came and they took slaves from India and from Pacacua, from Ciudad Colón,” Aguilar said, quoting the legend. “And so they made tunnels to dig gold, that’s why they call this place Río Oro. … They told the slaves that as soon as they found a certain amount of gold, they would be freed. And they found the right amount of gold, but they never freed them.

“So they (the slaves) diverted the course of the river so that the river would fill the mines and flood them, fill them with sediment. So the mine is called the ‘Mina Ahogada’ (‘Flooded Mine’ or ‘Drowned Mine’).”

In 1869 an Englishman named Robert Ross Lang acquired the old Fernández property, which became known as Hacienda Ross. Ross used an existing sugar mill on the grounds to produce cane syrup, which he sold to the National Liquor Factory (FANAL), according to an online history of the Santa Ana Conservation Center.

Because of a relationship between the Ross family and Minor Keith, who built a railroad from the Central Valley to the Caribbean that was completed in 1890, Hacienda Ross was said to have been the first settlement ever for railroad workers in Costa Rica.

Robert Ross died in 1907, the same year the canton of Santa Ana was proclaimed in the province of San José, officially gaining independence from the canton of Escazú.

The following year, a contract was signed to build Costa Rica’s second hydroelectric plant, in nearby Brasil. It was completed in 1912. Electric streetlights came along in 1913.

The cultivation of onions, for which the canton was long known, was believed to have been introduced around 1915. People from Santa Ana were often called cebolleros, “onion farmers.”

In 1918, Santa Ana was a major stronghold of the rebellion against the dictator Federico Tinoco Granados, who seized power in a military coup in 1917. According to Acevedo’s history of Santa Ana, clandestine planning for an armed uprising against Tinoco occurred at the adobe casona of Alberto Zamora, whose family still owns a winery near downtown Santa Ana today.

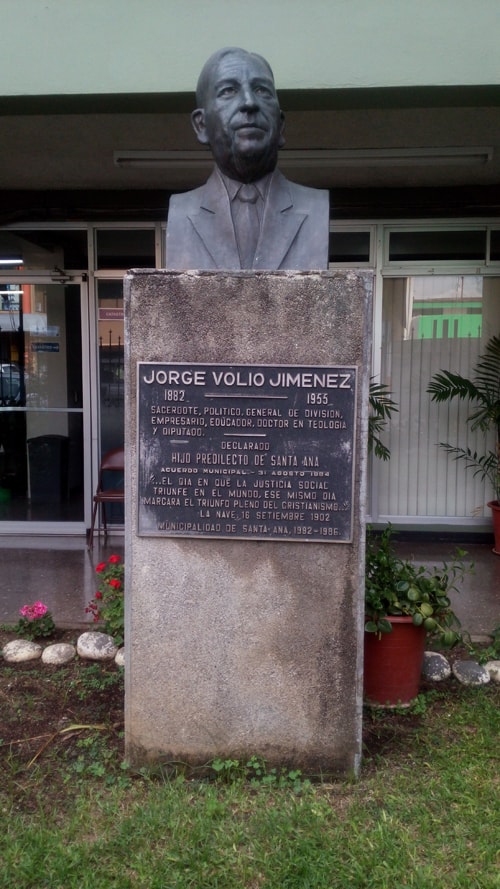

Among the leaders of the revolt were Jorge Volio Jiménez, a priest who is commemorated today by a statue outside the Municipal Palace of Santa Ana. Tinoco was deposed in 1919.

Meanwhlie at the old Ross hacienda, Robert’s heir Alejandro Ross Davidson planted rice, coffee and sugarcane. By 1918, he was one of the biggest sugar producers in Costa Rica, and he began exporting coffee from the harvest of 1932-33. This property would eventually become the Santa Ana Conservation Center, a zoo and agricultural museum.

Costa Rica’s first international airport opened in 1931 at Hacienda La Lindora in Santa Ana. With the paving of the highway, beginning in 1934, the old pueblo of Santa Ana was modernized and became an international gateway for Costa Rica. The main airport moved to La Sabana in 1940 and to Alajuela in 1958.

Santa Ana played an important part in the 1948 civil war between revolutionary backers of José Figueres Ferrer and Rafael Calderón Guardia, leader of the party then in power. One of the leading figures from Santa Ana was Marcial Aguiluz Orellana, a Honduran of humble means who had opposed dictatorships in Honduras and El Salvador before coming to Costa Rica, where he married the daughter of the owner of the haciendas of La Lindora, which he eventually inherited.

He fought on the winning side of the Figueristas in 1948, and in 1955 he led a group of santaneños against a counter-revolutionary movement launched by Calderón with the aid of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza García.

Aguiluz later served in the Legislative Assembly and helped found the communist-leaning Socialist Action Party (PASO), along with communist leaders he had opposed during the war. He ended up donating much of the property in Lindora for charitable and civic causes, and he was declared a favorite son of the canton of Santa Ana in 1982, four years before he died.

A “romantic era in Santa Ana communications” ended, according to Acevedo’s book, with the arrival of the first “automatic telephones” in 1966 and the closure of Don Pepe (“The Electrician”) Hidalgo’s old manual telephone.

“One of the few public telephones in the canton was located in Don Pepe’s house,” Acevedo writes. “Since the telephone was installed in a room where Don Pepe had a barbershop, conversations were generally in the public domain.”

Santa Ana was official recognized as a “city,” no longer a “villa,” and the seat of the Santa Ana canton in 1970. The following year, the traditional name of the area, “Valle del Sol,” or “ Valley of the Sun,” was officially adopted by the Municipal Council.

“As in the pre-Colombian era,” Acevedo writes, “the Santa Ana of today continues to be a strategic corridor. In June of 2003 a contract was signed to build the longed-for San José-Caldera highway, turning Santa Ana into a major crossroads and considerably shortening the distance between the provinces of San José and Puntarenas….

“Nevertheless, what appears to be progress for the canton could turn into a double-edged sword, worsening congestion in the streets of the city and contributing to ill-planned and excessive urban growth.”

These appear to have been prophetic words, as the one thing seemingly everyone complains about in what was once a tiny Spanish pueblo … is the traffic.

This article, one in a series on “Costa Rica’s Least Known Greatest Places,” is sponsored by Hotel Alta Las Palomas, a boutique luxury hotel between Santa Ana and Escazú, featuring the award-winning La Luz Restaurant. Contact Hotel Alta at info@thealtahotel.com or at 2282-4160.