U.S. President Barack Obama’s move to normalize relations between the United States and Cuba will resonate through baseball. The trickle of dazzling talent that already flows from the baseball-crazed island could turn into a geyser, a stream of available players that would force Major League Baseball to frame and police how teams acquire Cuban players. The political thaw would also eliminate the dangerous back channels of defection. The impact on the sport could be immense and, in the words of one team official, “drastic.”

Even with a political blockade between Cuba and the United States, players born in Cuba have shaped the game. White Sox designated hitter José Abreu earned last year’s American League Rookie of the Year. Tigers outfielder Yoenis Cespedes has won the past two Home Run Derbies. Outfielder Rusney Castillo signed a $72.5 million contract with the Boston Red Sox. Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder Yasiel Puig received a nickname — “The Wild Horse” — from no less of an authority than Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully.

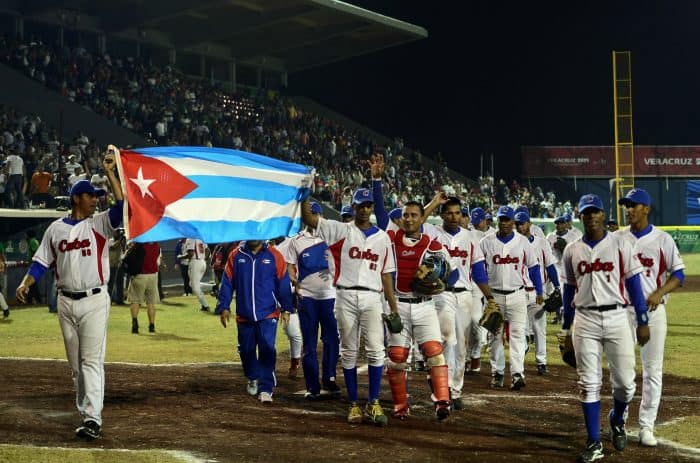

A new burst of talent may arrive from Cuba’s highest level into the majors and the upper levels of the minor leagues in the United States. Scouts would flock to youth tournaments in an attempt to discover teenaged players with huge potential and sign them on the cheap. Within a few years, baseball academies may spread across the island covered in the logos of major league teams, same as the patchwork of diamonds clustered around barracks-style dormitories strewn over the Dominican Republic.

On the day President Obama announced his intention to end the 53-year standoff, the league still waited for the situation to develop. Multiple high-ranking team officials declined comment, underscoring the topic’s sensitive nature.

“Major League Baseball is closely monitoring the White House’s announcement regarding Cuban-American relations,” the league said in a statement. “While there are not sufficient details to make a realistic evaluation, we will continue to track this significant issue, and we will keep our clubs informed if this different direction may impact the manner in which they conduct business on issues related to Cuba.”

The changes could come fast, because baseball prepared for this day. One Latin American scouting director, who has worked with Cuban baseball players since 1990, said he already has plans for the logistics of how to scout players on the island and the optimal place to build an academy. “I know what I would do,” he said. “I would just have to get approval from ownership.”

Latin American talent already saturates the sport, and the potential for a system in which teams can openly acquire talent from Cuba will only bolster the region’s influence. The Dominican Republic, with a population of roughly 10.4 million, accounted for 9.7 percent of the players on major league opening day rosters, according to MLB figures. The talent pool in Cuba, the scouting director said, is “on the same plane” as the Dominican Republic. The country has a population of roughly 11.3 million. Within a decade or so, baseball could see a demographic turnover of its talent pool of 10 percent or more.

“It would be a huge boon for the U.S.,” the Latin American scouting director said. “It would be another island that’s fertile. Then it gets confusing.”

Related: Costa Rica’s major league concern

Major League Baseball would need to determine what set of rules it implements for teams acquiring Cuban players. The league would hope for Cuban officials to allow it to use the same set of rules that apply in other Latin American countries: players over 23 would be considered free agents, and signing bonuses for players under 23 would be subject to spending limits per team.

But the Cuban government, as raised by Ben Badler of Baseball America, may provide complications. Cuba could put in place a system in which MLB teams bid for the right to sign top Cuban players, similar to the posting system used by Japan’s top league, except the money would flow to the government as opposed to a private league.

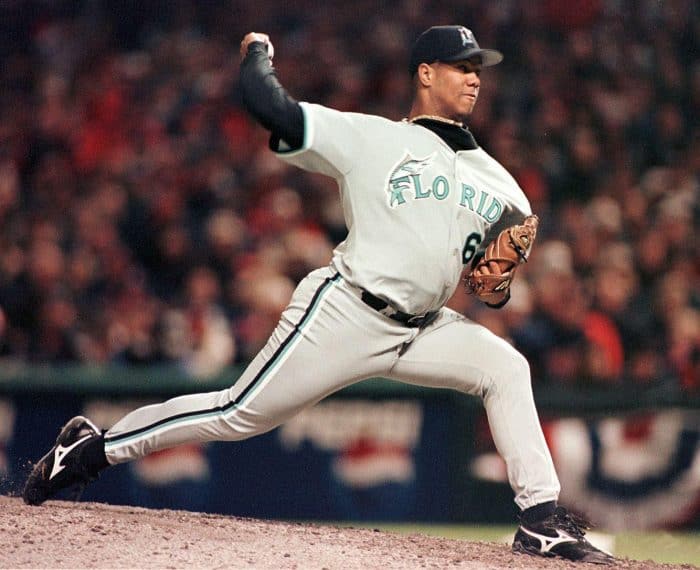

Cuban baseball already has made a lasting impact on the major leagues. Of the 186 players born in Cuba to reach the majors, 25 appeared last season. Their achievements created a Cuban golden age. Livan Hernández lifted the Florida Marlins to the 1997 World Series and threw the first pitch upon baseball’s return to Washington. The Cincinnati Reds’ Aroldis Chapman throws more 100-mile-per-hour fastballs than any pitcher alive. Outfielder Jorge Soler is at the core of the Chicago Cubs’ rebuilding efforts.

But as more players defected, the stories of how they arrived turned grimmer. For years, Cuban baseball players morphed into a dark cottage industry, a black market unto themselves, their talent inviting danger as it created opportunity. Smuggling and secrecy have imperiled defectors’ safety, robbed them of money and chiseled at their dignity.

Shadowy figures rubbed up against the baseball apparatus — prior to his arrival in the United States, Puig famously spent weeks in Mexico under the watch of men associated with the Los Zetas drug cartel. In 1999, pitcher Danys Baez snuck out of the Pan Am Games in Winnipeg without telling his family, friends or teammates, fearful of consequences. “You can’t tell anyone,” he said.

For years, the Cold War chill between the U.S. and Cuba left some of the most talented players in the world alone and vulnerable to exploitation. Now there is a real chance doors will open. Lourdes Gourriel, one of the top players still in Cuba, may now play in the majors without sacrificing his safety. His father, also named Lourdes, and his older brother Yulieski never had the chance. After Wednesday’s announcement, those kinds of missed opportunities may soon disappear.

Read all our Cuba coverage here

© 2014, The Washington Post