RIO DE JANEIRO — With just days to go before the presidential election here, a growing scandal has placed a number of issues center stage: They involve corruption, political machinations with the state-controlled oil company, and delays and overspending on a multibillion-dollar oil refinery that Brazil desperately needs.

A high-ranking former executive from Petrobras, the oil company, has just been released from jail to house arrest having turned state’s evidence.

His allegations have appeared in a steady stream in a weekly magazine, Veja — and they link payments in the refinery construction to politicians from incumbent President Dilma Rousseff’s Workers’ Party and other parties in Brazil’s ruling coalition.

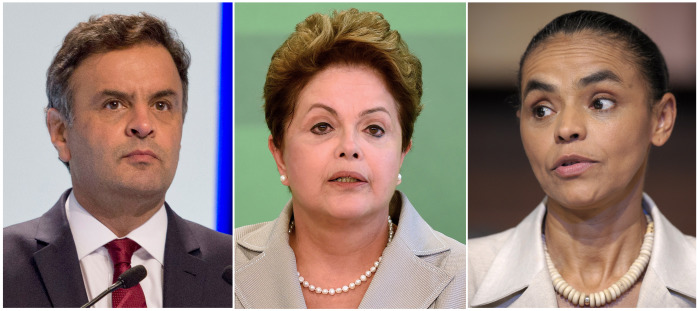

The first round of voting takes place Sunday. In a three-way race, Rousseff and Marina Silva are the front-runners, with Rousseff edging ahead, according to polls. Brazilians tend to be cynical about politicians, but the Car Wash scandal reaches deep into the long-standing apparatus constructed by the Workers’ Party, and no one is sure where it will lead.

Rousseff, a former minister of mines and energy and chairwoman of the Petrobras board, takes pride in her management skills. But the image of competence she has constructed is now taking some dents.

The scandal cuts deep in another way: Rousseff’s strength is among Brazil’s working-class voters, but amidst all the alleged overspending and mismanagement associated with the delayed refinery construction, some workers have come to feel badly treated and complain about not getting paid.

Rousseff’s opponents have gone on the attack.

“It’s shameful,” said Aécio Neves, the third candidate in the race, in a television debate on Sunday, as he took aim at Rousseff. “The denunciations don’t cease.”

Millions of dollars were allegedly creamed off inflated contracts for the Abreu e Lima refinery being built near Recife in Northeast Brazil. The refinery is to start operating in November, three years late. Its cost has ballooned.

A second Petrobras refinery project — Comperj, near Rio — is four years behind schedule, double the projected cost and delayed by strikes.

Petrobras eventually paid $1.2 billion for a third refinery in Pasadena, Texas, after a long court battle that ended in 2012, seven years after its previous owners had bought it for just $42.5 million.

While Brazil’s economy stutters, Petrobras hemorrhages cash importing the fuel Brazil can’t refine but urgently needs. And these enormous refineries have become emblematic of the barriers the country faces in building much-needed infrastructure — barriers created by mismanagement, corruption and overspending.

Prosecutors say the complex Car Wash scheme was run by Paulo Costa, now under house arrest and providing testimony, and money-changer Alberto Youssef, in custody. Police first arrested 28 people in March, having been alerted by “irregular” movements of $4 billion. Brazil’s Federal Court of Accounts has found overpayments of $99.2 million in just four contracts related to Abreu e Lima alone.

Evidence suggests “the possible involvement of various authorities … including federal parliamentarians,” a Supreme Court Judge wrote this week, in approving Costa’s state’s evidence deal.

Neves, the candidate for the Brazilian Social Democratic Party, alleges that Costa’s appointment in 2004 as a key Petrobras manager was political. “The corruption involving the company is much more serious than is being noticed,” a spokesman for Neves said in an email interview.

Brazil’s rumbling economic problems — the country is in technical recession — are also a central theme of this election, and opposition candidates point a finger at falling investment and lack of infrastructure.

“There are people who were involved in the running of the company who are involved in this corruption scandal. That does affect people who are planning to invest in the country,” said Aditya Banerjee, an analyst at a commercial intelligence agency called Wood Mackenzie, in Houston.

Petrobras is keeping its distance from Costa, whose job put him in charge of refining, and who was replaced in 2012. “Petrobras, in the condition of victim, is attending all the requests of the authorities and collaborating with the investigations, as the main interested party in clarifying the facts,” a company representative said in an e-mail interview.

Delays to the Abreu e Lima refinery were “principally for the need to repeat bidding because of excessive prices and delays in the acquisition of critical equipment,” the representative said, and did not comment on the cost increase — from $2.5 billion to $18.5 billion.

“It’s twice as much as any other refinery. Any other refinery would cost around $10 billion. So that’s massive,” Banerjee said. “It’s not just Abreu e Lima, it’s also Comperj.”

The Comperj oil refinery project, being built in Itaboraí near Rio, is due to start operating in 2016. Its budget has doubled to $13.2 billion. Brazil’s Federal Court of Accounts has found overpayments in the tens of millions of dollars.

The delay was caused by an “unsuccessful business model of partnerships,” Petrobras said. “In each investigation process, Petrobras is presenting its defenses and technical clarifications and has been able to demonstrate adherence of its practices to the norms and regulations in force,” a company representative said.

Comperj was paralyzed by a 40-day wildcat strike earlier this year that was blighted by violence. Riot police were called, a union car was set on fire and, on February 6, two workers were shot and injured.

The workers were on strike because they hadn’t been paid by their employer, a subcontractor, for months. Felipe Lima, a 22-year-old carpenter, was struck by two bullets. One went through his right hand; the other burst his pancreas. Rigger Françuelio Fernandes, 20, was shot in the hand and foot.

Speaking by phone from his home state of Ceará, in Brazil’s Northeast, Lima said he lives today on a sickness benefit and a one-time $2,000 payment from the construction-workers’ union. Money is tight. “I can’t work. My instrument of work is my hand,” he said.

Petrobras did not comment on the case as a police matter.

Money is increasingly tight for the oil company, too. Brazil is heavily reliant on road transport but can’t refine enough fuel to meet its rising domestic demand. Petrobras has to buy gasoline and diesel abroad at high international prices, which it sells at a loss because prices are fixed artificially low by the government to control inflation — currently running above target at 6.6 percent. This cost Petrobras a $1.5 billion loss over the past 12 months, according to figures calculated by the Brazilian Infrastructure Center, a Rio consultancy.

The Brazilian Oil, Gas & Biofuels Institute, IBP, recently called for fuel prices to be freed up. “The closer to international prices, the more they make investments viable,” said IBP president João Carlos de Luca in a phone interview. “Brazil needs refining.”

Rousseff’s opponents blame fuel price policy for hurting Petrobras, the environment and Brazil’s struggling ethanol sector, underpriced by cheap gasoline and diesel.

“We have a serious problem,” said Silva, from the Brazilian Socialist Party. “This is highly prejudicial to our country, and something the government needs to correct now.”

Petrobras’s ambitious development of Brazil’s ultra-deep water reserves, central to a $220.6 billion investment program, have also entered the fray. Rousseff attacked Silva, an environmentalist, as anti-oil.

The enormous costs of developing these reserves, coupled with the losses it incurs importing fuel, has put Petrobras in a worrying amount of debt — $114 billion at the end of 2013, according to Bloomberg.

But Petrobras is increasing production from those deep-water reserves. It promises to be producing 4 million barrels of oil a day, compared to the current 2.6 million.

Then they may finally be able to deal with their debts.

“Until then, we see things being pretty tight financially,” said Ruaraidh Montgomery, a senior analyst at Wood Mackenzie.

© 2014, The Washington Post