Last Saturday, July 19, marked the 35th anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution, which ousted Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio “Tachito” Somoza and his family in 1979 after a bloody and belligerent 43 years in power. But unlike the euphoria that seemingly enveloped the world back then, it doesn’t seem right to celebrate these days. Memorialize might be a more appropriate word for how to observe the anniversary.

What has happened in the past 35 years to convert a post-revolution Nicaragua marked by endless opportunity into a country of growing political hopelessness?

Fervor

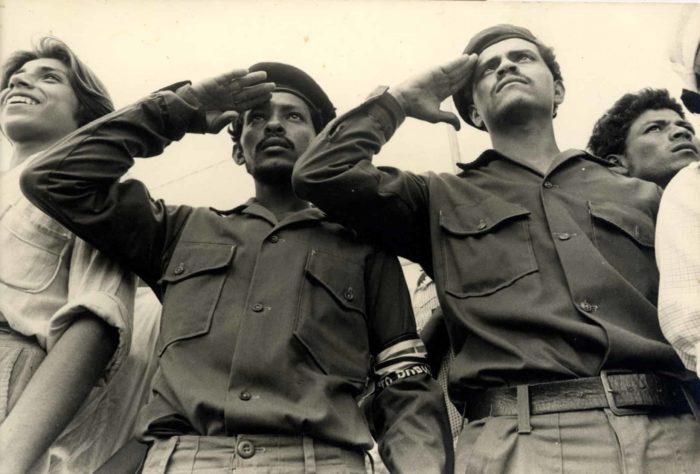

On July 20, 1979, The Tico Times led with a cover that proclaimed a “New Era in Nicaragua,” also noting in a separate headline that “Ticos Join Celebration.” Journalist Stephen Schmidt described the unfolding events:

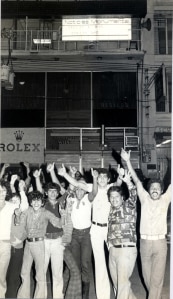

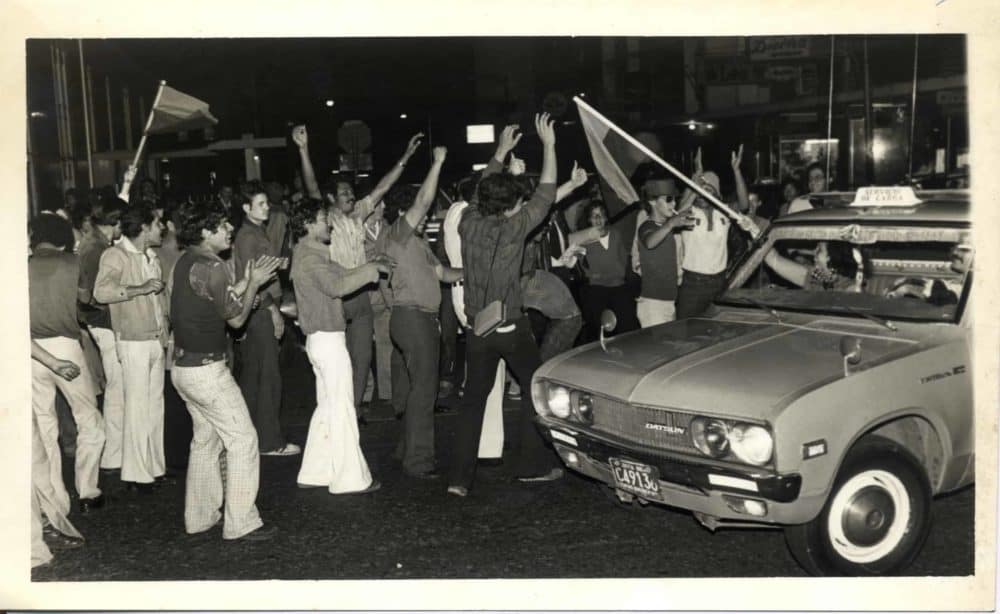

It starts softly at 2 a.m. The rhythmic honking of a couple of lonesome taxis echo through the empty streets of downtown San José, accompanied by the loud carryings-on of a handful of drunks.

Then the sirens go off. In Costa Rica, the sirens of Radio Monumental and Radio Reloj mean news… big news. Slowly, like a collective awakening from some bad dream, it begins to hit the josefinos: the news they’d been waiting three decades to hear is finally knocking them out of a sound sleep.

For most, it isn’t even necessary to turn on the radio.

Nicaraguan strongman Gen. Anastasio Somoza has resigned.

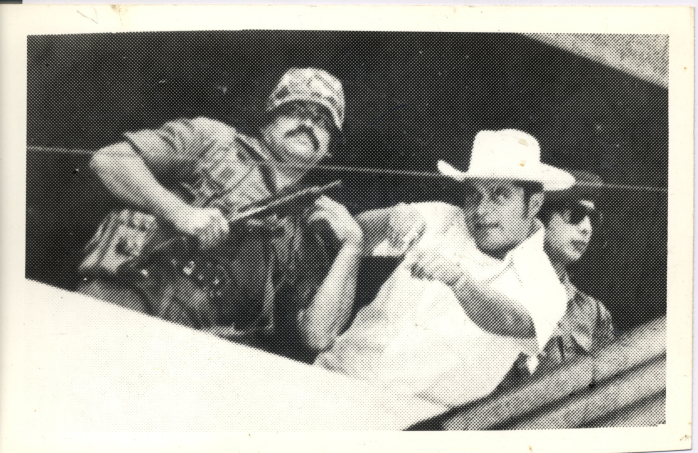

Even the old soldier José “Pepe” Figueres, then 73, was impressed by the young ragtag Sandinista soldiers. Figueres, who visited the guerrillas just days before Somoza abandoned Managua, told The Tico Times, “for me to be impressed by communists is really something.” He then predicted Somoza would fall “within the next two days.”

As predicted, “with mountains of suitcases and the remains of the fugitive leader’s late father and brother in tow, they were quickly esconced in Somoza’s Sunset Island mansion facing Miami Beach,” The Tico Times reported.

“It’s not just that they don’t want another Cuba, it’s that they know they can’t have another Cuba,” Figueres told Tico Times photographer LaVerne Coleman at the time.

Would Don Pepe say the same thing today? Probably not. In fact, it seemed the only Costa Ricans making a big deal of last Saturday’s ceremony in Managua’s Plaza La Fé were a handful of lawmakers and party leaders from the leftist Broad Front Party. On the Nicaraguan people’s dime, Broad Front Party Secretary General Rodolfo Ulloa traveled to Managua with party president Patricia Mora and three other lawmakers. After the ceremony, according to the daily La Nación, Ulloa touted Nicaragua’s plans for a $40 billion interoceanic canal as an opportunity for Tico workers to find jobs.

It also might have been an occasion for the Broad Front Party lawmakers to float their idea of joining the Venezuelan oil alliance Petrocaribe as a remedy to surging gas prices in Costa Rica.

Also in attendance last Saturday, according to the Nicaraguan weekly Confidencial, were Guatemala’s former Vice President Vinicio Cerezo, Panama’s former President Martín Torrijos, the ousted Honduran President Manuel Zelaya, Guatemala’s Nobel Peace Prize winner and indigenous rights advocate Rigoberta Menchú, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández and El Salvador’s President Salvador Sánchez Cerén.

Ulloa responded to criticisms back home, according to La Nación, by saying that he and other Costa Ricans in attendance felt it was “important to celebrate the fall of the Somoza dictatorship. Costa Rica’s contribution enabled that to happen in 1979. Here in Nicaragua, many Costa Ricans fought and died.”

Broad Front Party lawmaker Jorge Arguedas, who fought for the Sandinistas as a youth, noted that he carries the revolution “in his soul,” according to the Nicaraguan daily La Prensa.

Those statements in response to the criticism shouldn’t be downplayed. In all, some 30,000 people died in the Nicaraguan civil war to overthrow the Somozas and 300,000 were left homeless. (Some estimates say as many as 50,000 died.) Reconstruction of the devastated country was estimated at a whopping $4 billion – and that was before the Contra War, which began almost immediately after Somoza’s fall and lasted into the early 1990s. Costa Rica pledged its unwavering support for that reconstruction effort.

Stuck in San José at the time were three of the five members of the Junta of National Reconstruction: Violeta Chamorro, Sergio Ramírez and Alfonso Robelo. (Ortega also was a member of the Junta, eventually forcing the others out). To see them off triumphantly to Nicaragua, Costa Rica readied its traditional schoolchildren sendoff, accompanied by vice presidents José Miguel Alfaro and Rodrigo Altmann, President Rodrigo Carazo, Foreign Minister Rafael Calderón, Public Security Chief Juan José Echeverría and the five foreign ministers of the Andean Pact countries.

When Nicaragua’s interim President Francisco Urcuyo refused to relinquish power, calling on Sandinista rebels to lay down their arms in a bid to buy more time so his cronies could flee the country, Costa Rica’s Culture Minister Marina Volio told the Junta members, “I’ll go with you. I’m a woman and I’m not afraid.”

Much has happened since then, and it’s no secret the United States shares much of the blame for Nicaragua’s current economic and political conditions, particularly given the atrocious, misguided and illegal covert operations during the Contra War. But today, many of those same Sandinista fighters and leaders have become disillusioned with the Ortega administration and the direction of the Sandinista party, accusing Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo, of becoming yet another Somoza dictatorship.

For former guerrilla comandante Dora María Téllez, the war against Somoza was necessary. But the same conditions exist today as back in 1979, according to a report in La Prensa titled “Will history repeat itself?” Nicaraguans, Téllez argued, have been unable to defeat a caudillo culture.

In the same article, former Sandinista fighter Moisés Hassan notes that with the fall of Somoza, “the seeds of a new dictator” were sown. “For me, [Ortega] is a continuance of Somoza. Somoza didn’t die, his germs developed in Ortega,” Hassan told La Prensa.

‘Cristiano, socialista, solidario’

Night and day Nicaraguans are bombarded with the most recent Sandinista slogan, “¡Cristiano, socialista y solidario!” (“Christian, socialist and in solidarity”). Ortega and Murillo seem to have taken lessons from TV evangelists with the way they speak to the Nicaraguan people about politics, pettiness and poverty.

Have a listen to some of Ortega’s Saturday night speech/sermon (in Spanish):

Our roots are Christianity. That’s from where our values come. … To reach Sandino, first I arrived at Christ. To reach the Cuban revolution, first I arrived at Christ. To reach Marx, Lenin and Engels, first I arrived at Christ.

Since he mentioned Karl Marx, we’ll go ahead and make the point: Speaking of Christianity in the name of the guy who called religion “the opium of the people” likely would’ve left Marx aghast.

It isn’t just Ortega and Murillo doing this. Venezuela’s Maduro, a Roman Catholic who recently began following the teachings of the late Indian spiritual guru Sai Baba, often fills his political speeches with religious rhetoric to mythify his former mentor, the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez. Maduro considers himself Chávez’s “apostle.”

“Every day we believe more and more in the values of Christ, in his legacy,” Maduro said early last year during a stump speech ahead of the April elections, AFP reported.

Add political manipulation into the mix, and you’ve hit the caudillo jackpot. A report last week in Nicaragua’s Confidencial highlighted some troubling developments determined by Vanderbilt University’s Latin American Public Opinion Project.

Among the findings, the number of Nicaraguans who are willing to tolerate political opinions different than their own is steadily dropping, from 60 percent in 2010 to 47 percent this year. Only 4 percent of the 1,547 Nicaraguans surveyed said they are “very satisfied” with a democratic system of governance. Yet while their faith in democracy and their political tolerance of others is declining, the number of Nicaraguans who support their current political system is increasing, from 51 percent in 2008 to 68 percent this year.

Sociologist Manuel Ortega Hegg told Confidencial that he is concerned by the survey:

In a system where there is an increase in intolerance towards the rights of others, combined with enormous support for the political system – which permits or foments these types of attitudes – you have a group of respondents who create the conditions for an authoritative government to find support.”

According to LAPOP, 55 percent of respondents fear talking about politics among friends, while only 36 percent thought it is normal to do so.

Two other aspects of the LAPOP survey are insightful: questions about constitutional reforms passed earlier this year that could allow Ortega to become president for life (Ortega already has served three presidential terms, not including his post-revolutionary role as leader; he has run in every single election since: 1990, 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2011) and the plans for an interoceanic canal to rival Panama’s — which Ortega says will lift Nicaraguans out of poverty without providing a shred of evidence of exactly how such a massive project will be accomplished.

A staggering 70 percent of Nicaraguans surveyed by LAPOP after the reforms were passed said they were unfamiliar with the details. Most Nicaraguans didn’t even know what Ortega and his political followers in the legislature had done. Yet 75 percent said they knew about the canal plans, and of those, 54 percent said they supported it, saying it would “help the economy, promote tourism, generate jobs and improve the country’s image,” according to Confidencial. Only 10 percent of those who knew about it said they had negative opinions.

This seems to be the Ortega administration’s magic formula: The inhabitants of the region’s second-poorest country turn to their leader, out of fear or blind admiration, to pull them out of their financial woes.

The problem with politics

Overshadowing the rest of this year’s anniversary events were a series of attacks by unknown gunmen late Saturday night that resulted in five deaths and at least 19 wounded. The victims were Sandinista sympathizers returning from events marking the revolution’s anniversary in Managua.

One group allegedly armed with AK-47s attacked a caravan of buses on the highway from Managua to Matagalpa, La Prensa reported. A second group also attacked in Matagalpa. While four suspects were immediately arrested, one, a 16-year-old, was soon released. All four, according to family members, are Sandinista-affiliated, and all four – they say – are innocent.

Opposition groups immediately released statements condemning the attacks. Ortega called it a “massacre.” Fusion’s Tim Rogers noted that one previously unknown group calling itself the “Armed Forces of National Salvation (FASN-EP)” took credit on Facebook for the violence.

Former Contra leader Roberto Ferrey told Fusion the attacks, “the most brazen act of political violence to rock Nicaragua in nearly two decades, could reignite a tinderbox in a dangerously polarized country.”

As Rogers noted, those who usually suffer in such matters are the almost half of Nicaragua’s 5.9 million people – 43 percent – who live in poverty. According to the World Bank, Nicaragua is perhaps the only country in the Western Hemisphere where per-student spending on secondary school students (junior high and high school) is less than half of spending on primary school students, which is about $197 per student. Of approximately 400,000 children currently between the ages of 3 and 5, an estimated 179,000 will receive no formal education.

Then there are the low salaries versus cost of living. In 2012, the prices of 23 items in the basic food basket increased by 2.9 percent, yet the lowest salaries cover only 25 percent of this basic food basket. The average minimum wage can afford to buy only half of these items.

Despite this, Nicaragua’s gross domestic product growth last year was an impressive 4.6 percent with 7.1 percent inflation, according to the World Bank. Foreign direct investment topped $1.5 billion last year, and that figure is growing. So what gives?

The new millionaires

Last year, Nicaraguan opposition lawmaker and former Sandinista militant Enrique Sáenz stumbled upon a global report on new multimillionaires. The report defined a multimillionaire as someone who earns more than $30 million per year. According to that definition, Sáenz found that Nicaragua has 190 multimillionaires, up from 180 – an increase of 10 during the Ortega administration. By comparison, Costa Rica has 85, Panama 105 and El Salvador 145. Sáenz noted that El Salvador’s economy is three times the size of Nicaragua’s, while Panama’s economy is four times its size, and Costa Rica’s economy is five times its size.

Sáenz also drew attention to Ortega’s “eccentric” travel habits, which often include trips with members of his family who hold no discernible government posts.

“Ortega is one of the wealthiest people in Central America,” Sáenz told Diario Las Américas. “He can’t avoid the temptation to travel in luxury.”

One trip that stands out, Sáenz said, was in May 2013 to neighboring Costa Rica for a Central America presidential summit with U.S. President Barack Obama. Ortega, the only leader not in a suit and tie, arrived on the second largest plane of the presidential delegations, surpassed only by Obama’s Air Force One. The estimated cost of the flight: upwards of $42,000.

Two days later, Ortega and his family traveled to Venezuela for a Petrocaribe summit, a trip some estimate could have cost six times as much as the Costa Rica flight. (Former Nicaraguan Presidents Violeta Barrios and Enrique Bolaños always traveled on commercial airliners, Diario Las Américas pointed out.) Carlos Tünnermann, former education minister during the Sandinista Revolution, noted that with the money spent on the Costa Rica trip alone, Ortega could have built two rural schools and four homes for poor families.

A 2011 story by Mexico’s El Universal highlighted that since 2007, the Ortega-Murillo family has widely expanded their personal business empire, acquiring interests in petroleum, energy, TV and radio, agriculture and livestock and tourism. But the separation between political and personal wealth has long since disappeared, as there is no real accounting as to what money belongs to the state, and what belongs to the Ortega-Murillo family.

Marcos Carmona, executive director of the Permanent Human Rights Commission, told El Universal:

In 45 years, the Somoza family dictatorship [which governed from 1934 to 1979] didn’t make as much money as President Daniel Ortega has in less than five years at the helm of the government. Somoza had nothing for [Ortega] to envy. … The presidential family has been amassing wealth, they live wastefully and with great opulence, with no state control over the wealth and resources they receive.

It’s a contradiction to see a president who says his government is for the poor but who drives a vehicle that costs dozens of thousands of dollars, while the people have extreme needs: There are more than 500,000 children living in misery in the streets, more than 40 percent of Nicaraguans survive on $2 a day, and 30 percent live on $1 a day.

Most of that money initially came from Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez, who died last year of cancer. Some of it came from the late Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi, who died in a revolution in 2011.

According to El Universal, of the 10 million barrels of crude oil Nicaragua began purchasing from Venezuela each year starting in 2007, at a cost of up to $900 million, half was paid within 30 days. The rest could be paid off in 25 years. The operation was completely privatized and run by Alba de Nicaragua SA (Albanisa), a company supervised by the Ortega-Murillo family. Albanisa generated up to half a billion dollars per year, while maintaining a monopoly on the importation of oil.

A 2010 report by the Venezuelan NGO Economic Research Center of Venezuela noted that Chávez had promised Nicaragua some $7 billion in direct aid. In 2011, Nicaraguan media, citing the Central Bank, reported that $1.6 billion of that already had been dispersed. Some of that money went into state coffers. The rest of it went to Albanisa and Grupo Alba, two organizations controlled in Nicaragua by Daniel Ortega.