I once got a speeding ticket for going about 30 kph over the posted speed limit on the Costanera Sur highway near Jacó. While 30 kph may sound like excessive speed, the actual, unrealistic speed limit was 80 kph, which few drivers obeyed. I was unlucky in that the Tránsito officer standing on the side of the road singled out my car for his radar gun. I was lucky in that the fine was only around $30 USD in colones. It was a year or so before the Costa Rican legislature went from one extreme to the other in determining the fines for various driving infractions.

Had that happened today, my fine would be 245,000 colones, or about $500. The sudden spike in fines was partially due to the low fines for driving under the influence. There was a series of fatal crashes caused by drunken drivers behind the wheels of tractor trailers. The fine for drunk driving was absurdly low, and it took this chain of disasters to spur change. Unfortunately, lawmakers went overboard with all of the fines when updating the one for drunk driving, which is now a justifiable 363,000 colones.

I have a nephew who recently learned firsthand the financial punishment of breaking even minor laws while driving. He lives in a remote village on the Osa Peninsula, only a few kilometers from an entrance to Corcovado National Park. He routinely rides his motorcycle from his home in town to his mother’s farm, located a few kilometers away on an unpaved road of ruts and potholes.

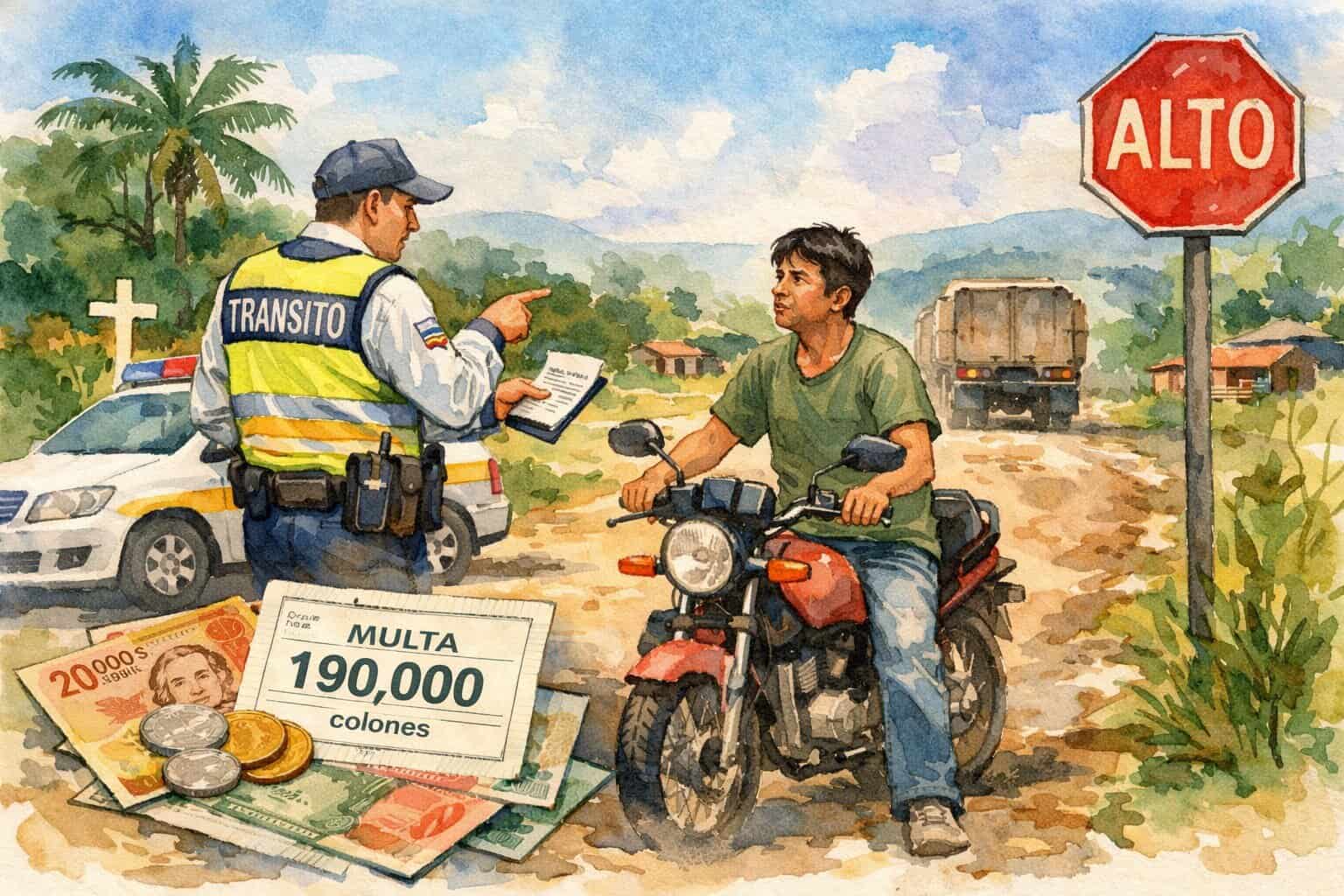

The town has one stop sign at the main crossroads. On a recent Sunday morning he was on his way to the farm when he was stopped by a Tránsito officer. Like the majority of motorcyclists riding on the remote roads of the Osa, he was not wearing a helmet. And according to the officer, he did not come to a complete stop at the stop sign. No matter that there was no one else on the road at the time. Total fine for the two infractions: 190,000 colones.

My nephew works hard at a number of low-paying agricultural jobs to support his family. He was traveling a rural road he has ridden daily for years without an accident. The top speed in the village is not much faster than I could do on a bicycle. These surprise Tránsito roadblocks actually do little to improve the safety of highway travel here. Their main purpose seems to be a gotcha moment that translates to collecting as much money as possible from drivers caught unaware.

Then there is the irony of my nephew taking this monetary hit while driving on a road that has not even been graded in months.

Yes, as a judge once told me in court here, we are a nation of laws, some enforced much more strictly than others. An hour to the south, our neighbors in Panama levy lighter fines for the same infractions, and of course have a superior system of highways and roads. But up here most everything costs more, including traffic tickets.

That my nephew broke the minor laws is not arguable. The real injustice is that the fines levied in this instance are out of proportion to both the severity of the infractions and the relative income of the average motorcycle-riding campesino in the rural zone.