She was identified as a “transvestite man” when her body was found in an abandoned lot near the Justice Tribunal of Limón. She died in a country that didn’t recognize her identity, not even in the final moments of her life, nor after her death. The failure of public policies and apathy are complicit with the fact that in Latin America, transgender people such as Kenisha have life expectancies of a mere 35 years.

She wore a wig and a short skirt. She frequently walked through the red light district of Guápiles. She was involved in prostitution because it was the only option that would allow her to eat and fund her transition. She took advantage of the darkness of abandoned lots, close to the Justice Tribunals in San José to offer her sexual services. Kenisha, 15 years old, walked between those bushes on the last night of her life.

She identified as a woman, while her sexual organs were biologically male. That is to say, she was a transgender woman. Her body was found half-naked and with signs of asphyxiation on the morning of August 14, 2017. A neighbor who passed by the site saw a pair of shoes thrown amidst the undergrowth, called a mechanic who worked 20 meters away, and later gave advice to a judicial agent.

To this day, the Judicial Investigation Police (OIJ) keeps the homicide case open. When interviewed, the head of the regional office, Teodosio Rivera explained that the case was still inconclusive.

Kenisha’s mere gender identification could have provoked her murder. A hypothesis is that one of her clients was her murderer.

However, the data on Kenisha’s murder ignore the fact that she was a transgender woman. For official purposes, she is treated as a boy who dressed like a woman. Some media outlets referred to her as a transvestite when covering her murder.

This occurred with other deaths and aggressions against transgender people which are hidden among official statistics: this data is limited to biological sex, not the gender identity or sexual orientation of those concerned, explained Orlando Corrales, the head of the Criminal Analysis Unit of the OIJ, after admitting that the Costa Rican government does not know the number of trans people or people in the LGBTQI (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex) community who have been murdered.

In Latin America, the life expectancy for 80 percent of transgender people is 35 years, according to the Registry of Violence against the LGBT Population created by the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) between January 1, 2013, and March 31, 2014. The report was released in 2015. This study did not include Costa Rica, because these registries did not exist here.

For reference, Costa Rican life expectancy is, on average, 80 years: that is to say, more than double that of a transgender person in Latin America.

Police Chief Teodosio Rivera recognizes that at the level of the police forces, there is a lack of knowledge of issues related to gender identity.

He says that in addition, research is “difficult” in these types of cases, as people tend to remain silent about what they know: clients of trans women involved in the sex trade do not want anyone to know that they bought these services, the women’s families are not open to speaking, and other transgender individuals who engage in prostitution are suspicious of the police.

“Our society still has a lot of machismo (cultural masculinity) and religious values which stipulate that in every situation, the home must be formed by a man and a woman. Therefore, when society sees two women or two men who are embracing or kissing, they are marginalized in all of these situations. And while it is good that the new society is searching… for a situation of equality and equity, it is clear is that there is still a lot to be done. This is what brings us to how these violent situations are caused,” Rivera said.

The Organization of American States (OAS) says that the lack of statistics on the deaths of transgender people means that an entire section of the population is being ignored.

“Procedures for obtaining statistics are necessary to measures, in a uniform and precise way, the prevalence, tendencies, and other aspects of violence in a determined state or region,” the OAS states. “Detailed analysis of these statistics provides the necessary information and understanding to authorities so that they can design public policies to prevent more acts of violence.”

Luis Eduardo Salazar, of the current administration’s Presidential Commission for the LGBTI Population Affairs, recognizes that historically, these populations have been invisible within statistics

“As a result, in 2018 we have a marked absence of data that could support public policies in the future,” Salazar said. “For this reason, one of the issues that the commission is most interested in is collecting data about the entire LGBTI population. Our goal is that in the 2020 census, we can incorporate sections related to gender and sexual identity, as other countries have done in the past.”

“As a commission, we hope that by the end of this administration, we will have concrete data about the LGBTI population of the country that can serve as a basis for public policies in the future,” he indicated.

Hidden Figures

According to the CIDH, there is a close relationship between exclusion, discrimination, and the short life expectancies of transgender people. According to the information received by the Commission, “violence and discrimination against boys, girls, and young transgender people start at a young age. They are already generally expelled from their homes, schools, families, and communities, as a consequence of expressing their diverse gender identities.

“As a result, transgender people face poverty, social exclusion, and high rates of lack of access to housing, pressuring them to work in the criminalized informal sector, such as sex work or having sex for survival. As a consequence, transgender women are profiled by the police as dangerous, making them even more vulnerable to political abuse, arrest, and being imprisoned,” says the CIDH report.

The crime involving Kenisha matches this reality. Her death is not only attributable to the person who killed her, but also to a country that abandoned her and didn’t give her opportunities.

Despite the fact that Costa Rica lacks official data on the quantity of crimes or aggressions against transgender people as well as details pertaining to these attacks, organizations such as Transvida and Redlactrans started to collect their own data in 2017 that was shared with Proyecto Punto y Aparte and Semanario Universidad.

The data collected to date reveals that 30 percent of aggressions suffered by this population are committed by individuals, 17 percent by the police, and another 15 percent by other public workers.

These figures also show that these aggressions primarily occur in places where sex work takes place, and that the age of the victims is mostly in the range of 26 to 35 years, which coincides with the statistics of Latin America.

All of these data tells us stories – stories whose protagonists’ lives are in danger, like the transgender individual Janeth Salgado, who was a sex worker and is now an activist.

“From the moment I got into the car, I felt a bad vibe,” Salgado recounts. “I saw that I could not open [the door] from the inside, only from the driver’s side. The man took me to El Infiernillo of Alajuela, to a [vacant] lot. There he put a knife to me and raped me. Afterwards, he tried to stab me. I had to run away. It was a desolate place, and he followed me with the intent of throwing me into the car. I had to hide. I had to walk 5 kilometers in the dark.”

In her mind, there are also vivid memories of close friends who add to the list of mortal victims.

“Previously, there was a young woman who was like a girl. She was called Natalia Novoa, she was around 19 years old, she was there near the Ricardo Saprissa [Stadium] when two men and a woman arrived in a car and assaulted her. They shot her in the head.

“In Cartago they killed a young woman around two years ago; what they did to her was very horrible. They punched her, tied her arms and then fired about 20 bullets into her face. It was so horrible. Because she was someone who didn’t mess with anyone,” recounted Salgado.

According to Transvida, 70 percent of aggressions go unreported – in part due to the fear that victims have for the authorities, who sometimes are the aggressors.

Who killed Kenisha?

Kenisha lived among the claims and the religious teachings of her mother. Her transgender identity was not understood by her family.

“I advised her to change that life, since with the power of the Bible it can be changed, but there was no way,” laments Agueri Garita, Kenisha’s mother, who is still struggling today to bury her dreams of her “dear son” studying, working, and having a family.

Listen to Kenisha’s mother speak about her child

“From around the age of 13 [she] wanted to use makeup; it was like a demon possessed [Kenisha] ever since that little boy was small. Then [she] didn’t want to go back to school, [Kenisha] was only missing sixth year,” the last year of high school, Garita says.

Listen to Kenisha’s mother speak about her child

According to the data compiled by Transvida, only four out of 100 transgender people graduate from secondary school.

Kenisha also wanted to feel comfortable with her physical image, to “transition” to the image of the woman she felt she was. Without enough money to pay for hormone replacement therapy (HRT), she wore wigs, makeup, and clothes.

According to Transvida reports, 63 percent of the discriminatory acts experienced by transgender people are instigated by public workers or police officers.

A lack of opportunities cornered Kenisha in the world of these statistics, which show that 83 percent of transgender people are involved with prostitution and that 25 percent of those who are killed are found in areas where sex trade occurs, according to data from the report by Cedostalc de Redlactrans and Transvida.

The Murdered Transgender People Observatory, based in Germany, identified Latin America as an area of high risk, since, of the 2,264 homicides of transgender people that occurred in 68 countries between 2008 and 2016, 1,768 cases were in Central and South America.

In the district of La Emilia, in the Caribbean slope town of Guápiles, Kenisha is remembered by her neighbors a child full of happiness who had the ability to make friends and “the capability to take food out of her mouth for another person.”

However, that child has now taken her place on the disappointing list of victims of what some international movements have called “social assassination,” discriminated against and without opportunities, hoping that the rights gained by the LGBTQI in Costa Rica’s capital will one day reach the province of Limón.

Such a murder is committed not only by the executioner, but also by a society whose transphobia and rejection brings about many deaths: through homicide, lack of medical attention, or suicide.

A study conducted in 2016 by the National Center for Transgender Equality in the United States determined that 40 percent of the transgender people surveyed had planned to take their own lives at some point.

Impunity

Costa Rican legislation does not include hate crimes in the Penal Code.

According to Larissa Arroyo, a lawyer specializing in human rights, reform is required to include a crime that covers this term.

Furthermore, Arroyo says that Costa Rica needs to create a “culture of reporting” such crimes, forcing the government obliged to “react”

“It is totally understandable that transgender people do not report [crimes]. They usually occur in populations which have historically been vulnerable, including women, and they are in another way re-victimized: that is, they are [expected] to report when they do not have the conditions to manage it, and this is really very problematic, to say the least,” said the lawyer.

Jess Márquez, a transgender man who writes a website, published a letter months ago, for Kenisha and what her death represented for the LGBTQI population.

“I repeat this cry of transgender people, because they attack us, they exclude us, they make us invisible and ultimately, they kill us. Because your [Kenisha’s] death is not seen for what it is, a hate crime. It is simple: if the logic is that we should not exist, why should it be bad that they kill us?”

“It is, because we are human. Because we have a right to life and to respect, to work, to be healthy, to study, love, have a family, to exist. And today, Kenisha, people have taken oaths upon [your memory]: I will remember you forever and I will not leave your murder unpunished, nor will I let your identity be ignored.”

“Today you died, but all transgender people recognize that we share your fate and we cry over your death,” Jess wrote.

According to Jess, the impact generated by Kenisha’s case was significant: her story reminds us that something as small as a glance on the bus can turn into a murder instigated by hate.

The OAS explains this fear: the state of social discrimination in which transgender people live creates a cycle of poverty and exclusion which makes them more vulnerable to being victims of violence at the hands of state and non-state agents.

Commissioner Salazar indicated that he recently met with the Citizen Action Party (PAC) legislator Enrique Sanchéz, with the goal of creating a working group that would aim to develop a bill to codify hate crimes.

“This implies, of course, a legal study comparing and analyzing experiences of other countries. It is fundamental that as a country we have a law that answers to crimes brought about by different forms of discrimination, such as that on the basis of nationality, ethnicity, religion, and, of course, sexual orientation and gender identity,” he said.

Looking Forward

Among the positive actions that have served to counter discrimination against this population, last year, the Costa Rican Social Security System (Caja, or CCSS) published the “National Regulations for Health Care Free of Stigma and Discrimination for the LGBTI Population,” which intends to safeguard health care access for this population.

According to the activist Keyra Martínez, these regulations were one of Transvida’s struggles: ensuring that the Caja recognized their identity and gave them discrimination-free treatment, both in San José and rural areas.

However, Martínez says that more work is needed in this respect:

“It could be that the doctor is used to the issue: if a transgender girl arrives and presents herself as female, she will have her identity respected. But what about the guard who receives her at the door and the receptionist who sees her before the doctor? If these people are transphobic, the girl will suffer an aggression,” Martínez states.

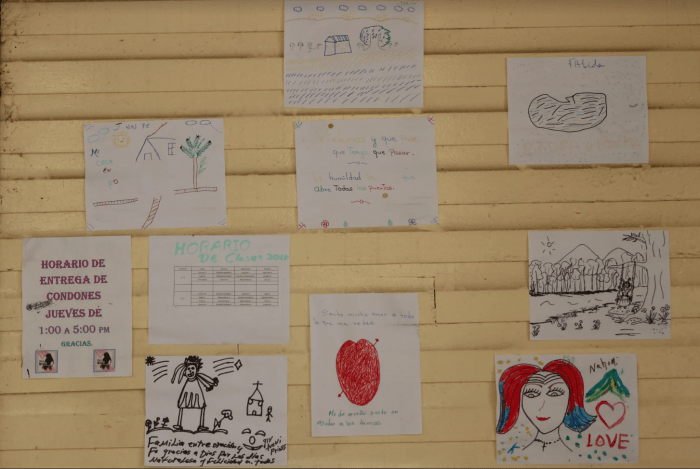

Transvida not only fights for the rights of this population, but also provides support and educational opportunities, work, and access to other rights, according to Martínez.

For her, the creation of public policies that guarantee the well-being of transgender people and recognition from the Legislative Assembly are at the top of the to-do list, since transgender people are still rejected by some political groups. Parties such as the National Restoration Party deny the existence of transgender people.

Increased violence against LGBTI community reported in Costa Rica

She pointed to positive changes that have occurred as a result of Executive Decree Number 38999, from the administration of Luis Guillermo Solís. The document declares that the presidency and members of the government are institutions free from discrimination, and suggests that these kinds of actions must be part of a permanent reality in Costa Rica.

“Before Transvida we were only known as a group of ‘transvestites’ or as ‘homosexuals’ (playos), strange people dressed as women. Ever since Transvida existed, we have finally been recognized for who we really are,” Martínez said.

For lawyer Arroyo, however, one of the difficulties that remain is that there has not been a portion of the budget assigned to carry out this decree.

Arroyo says that another positive aspect was the consultative opinion of the Inter American Court of Human Rights requiring that member states, including Costa Rica, allow official name changes related to gender identity. She says the Supreme Elections Tribunal (TSE) has “partially” started to carry out this change, but that the changes have been too gradual.

“That is one of the ways to improve quality of life: it is not too difficult, and it has been delayed incredibly,” Arroyo said.

The specialist in terms of human rights added that other actions must focus on incorporating a culture of respect for gender diversity and an educational environment that permits such diversity – for example, full access to education and health care. Furthermore, she mentioned the importance of affirmative action for the incorporation of transgender people into the workforce.

Commissioner Salazar, meanwhile, enumerated a series of actions that the current government must carry out under the leadership of President Carlos Alvarado.

For example, he mentioned that training and sensitivity training will be increased for public workers.

“These training programs have been developed over the course of several years and must be strengthened – especially for people who are a part of essential services such as health, as well as for National Police Force officials, about whom we have had reports and incidents of abuse of force,” he said.

An evaluation of the state of LGBTI Healthcare will be carried out, according to Salazar. With respect to name changes on identity documents, “the Executive Branch will soon approve the procedures and documents provided by the Public Administration so that they will be appropriate for ID Card changes,” he said.

Salazar added that “commendable actions have been carried out so that the transgender population can receive an educational program from the Ministry of Public Education (MEP) so that they can obtain their diploma,” and that the National Training Institute of Learning (INA) has provided training to the transgender population. These efforts will be redoubled by public universities and others organizations such as the National Institute for Cooperative Development (Infocoop) “so that transgender people can succeed”.

“The idea is that transgender people supported and integrated into the work force, and this would favorably impact their socioeconomic situation,” Salazar said. “This, in turn, will benefit the country.”

This special report was prepared for Semanario Universidad as a part of the Punto y Aparte journalism education project by Carlos Andrés Madrigal, a regular freelancer for The Tico Times, and translated for The Tico Times by Jack Stanley. Read the original report here.