On Feb. 4, 2018, Fabricio Alvarado – a presidential candidate who just weeks before was at only three percent in some polls – capped off his upward surge by winning the first round of voting in Costa Rica’s national elections. In no community did he receive a higher percentage of votes than in Pocora, Guácimo, in the province of Limón.

The Tico Times is pleased to translate David Bolaños’ in-depth feature, originally published by Radioemisoras UCR and the weekly Semanario Universidad examining the factors that led to Alvarado’s massive support in Pocora. Part II of IV.

In addition to its support for Fabricio Alvarado’s National Restoration Party (PRN), Limón showed the second-lowest voter turnout in the country on Feb. 4. Only in Guanacaste did fewer people head to the polls.

In Pocora, only six out of ten people voted.

According to the inhabitants of Pocora, Carrandí and Matina, the campaign ranged from political disillusionment and hope for change.

Those three settlements are home to more than 27,000 people, according to the National Statistics and Census Institute (INEC). These are districts surrounded by pineapple or banana plantations, where the roar of trucks passing by on the freeway never ceases.

Almost half of the homes in Pocora and 57 percent of the homes in Matina experience multidimensional poverty. A report carried out by investigators from the University of Costa Rica (UCR) Economical Sciences Research Institute established these percentages based on the 2011 census.

This compares to a multidimensional poverty rate of just 18.8 percent on a national scale, according to the 2017 National Homes Survey (ENAHO).

The UCR study indicates that the most extended scarcities in area homes are lack of human capital and of Internet access.

In this context of disillusionment and the desire for change, the missing piece was a candidate to channel those feelings. That opportunity showed its face on Jan. 9, when the Inter-American Human Rights Court issued its ruling on gender identity and non-discrimination for same-sex couples in its member countries, including Costa Rica.

In the 2014 elections, the evangelical Restoration Party received only 42 votes of the 2,600 that were cast in Pocora. Residents admit that Fabricio Alvarado was rarely mentioned when the 2017-2018 campaign began, but the court ruling changed all that.

Following the ruling, the candidate put himself on the political map with speeches about values, family and the principles, with proposals such as “eliminating gender ideology,” overturning the executive decree that regulates in vitro fertilization (IVF) in the country, and removing Costa Rica from the Inter-American Convention of Human Rights.

Unlike preacher Pedro Cubero (see Part I), the majority of pastors we interviewed in Pocora, Matina and Carrandí denied promoting Alvarado in their congregations, and all of them added that the candidate didn’t visit their communities.

Nevertheless, the pastor and elementary teacher Ana Yaney Mora said that she did urge her hundreds of congregants in Pocora to “assess the principles and values” of the candidates to decide whom to support.

The clerics indicated there was a “click” that their congregants made on their own, guided by the principles that Alvarado promises to uphold.

The candidate’s emphasis on traditional values helped him stand out from the pack, according to María José Cascante, deputy director of the University of Costa Rica’s Center for Research and Political Studies (UCR-CIEP).

“The key to this election has been finding a topic that polarizes. When it comes to fiscal issues, the differences can be difficult for citizens to notice, but aligning our values is simple,” Cascante said.

Post-electoral research from CIEP indicated that most people who supported the PRN in February said their priority was “defending traditional values.”

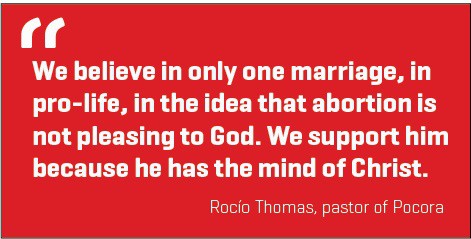

In the locations we studied in Limón, being against abortion or same-sex marriage are the touchstones that Alvarado’s supporters mention most when explaining what they mean by principles and family values.

“The Christian principle,” responded María del Carmen Vallejo, who live in Carrandí. She’s Nicaraguan, but counseled her daughter, a Costa Rican citizen, on how she should vote.

So, what is “the Christian principle”?

“What our parents accustomed us to. That with God made man and women,” responded Vallejo.

“We support him because he has the mind of Christ,” said the Pastor Thomas.

This article was originally published in Spanish at Radioemisoras UCR and Semanario Universidad on March 6 by journalist David Bolaños, and was translated by The Tico Times with the permission of those media partners.