Costa Ricans turn out to vote for their president and legislators in numbers that would be the envy of political organizers in the United States. During the first round of the 2014 general election, nearly 70 percent of eligible voters cast ballots, a participation rate that’s typical for the country in national races.

But a similar percentage of voters stayed away from the polls in the last municipal elections in 2010. The official turnout rate was 28 percent, and that was an improvement over the previous municipal election cycle.

Meanwhile the percentage of eligible voters who cast ballots for the mayor of San José – Costa Rica’s capital, the most populous canton and the one with the biggest budget – was just 18 percent in 2010, according to figures from the Supreme Elections Tribunal (TSE), which oversees elections in Costa Rica. Again, this was an improvement over 2006, when just 12 percent of eligible San José voters cast their ballots.

Lawmakers and election officials are hoping that a series of changes to the way municipal elections are run will boost citizen interest, and in turn boost the number of voters who head to the polls next month. This year’s turnout will test the new elections law and whether political parties can muster enough enthusiasm to buck decades’ worth of apathy when it comes to choosing city leaders.

The upcoming mayoral elections — scheduled for Sunday, Feb. 7 — for Costa Rica’s 81 cantons mark the first time voters will elect local representatives midway through the presidential and legislative terms. In the past, local elections have been held the same year as presidential elections but in a different month.

The office of mayor, or alcalde in Spanish, is relatively new in Costa Rica. Up until 2002, voters cast ballots for a political party and those political parties would select a roster of candidates for city council seats. Each party would then be awarded a certain number of seats based on the percentage of votes it received. (This is the same system still used to elect national lawmakers.)

Once the council was formed, members would elect a “municipal president” who acted as mayor.

But in 1998, lawmakers passed a law doing away with this parliamentary system in favor of direct election of mayors. City council members are still elected through the old system.

The change doesn’t appear to have enticed people to vote. Plus, local media has, until recently, shown relatively little interest in municipal campaigns, exacerbating the lack of interest from voters.

In 2010, lawmakers sought to fix what they saw as another problem with municipal elections. They thought voters were more likely to vote a straight-party ticket, rather than truly evaluate the candidates, if municipal elections were held close to or at the same time as national elections. So they passed a law moving the subsequent municipal election back two years, to 2016, so that it would alternate with the general election.

Some observers also hope the change will encourage more civic participation because local elections won’t be overshadowed by the money, prestige and advertising power of national races.

How much does the mayor matter?

Constantino Urcuyo, a political analyst and former Social Christian Unity Party (PUSC) lawmaker, said part of the reason for high abstention rates in municipal elections is that municipalities don’t have much power or money relative to the central government.

“People don’t feel that the municipal governments have much impact on their lives,” Urcuyo said.

In reality, municipal governments are charged with maintaining streets (75 percent of roadways in Costa Rica are municipal), handling wastewater and trash collection, giving out construction and business permits, and providing opportunities and spaces for recreation and cultural activities.

Ironically, cantons with relatively small budgets tend to see higher voter turnout than their wealthier peers, according to a recent analysis by the newspaper El Financiero. That means that those people who do vote in the wealthier cantons of Costa Rica have an outsized influence on how money gets spent in their community.

But some wealthier cantons have achieved some of the political independence that lawmakers hoped would come with moving municipal elections to off years. In the San José area, for example, the wealthy cantons of Curridabat and Escazú both elected canton-based parties into power in 2010: Curridabat Siglo XXI and Yunta Progresista Escazuceña, respectively.

This year, Johnny Araya, former National Liberation Party presidential candidate and mayor of San José for more than 20 years, has thrown his hat back into the political ring under a new party called Alliance for San José (ASJ).

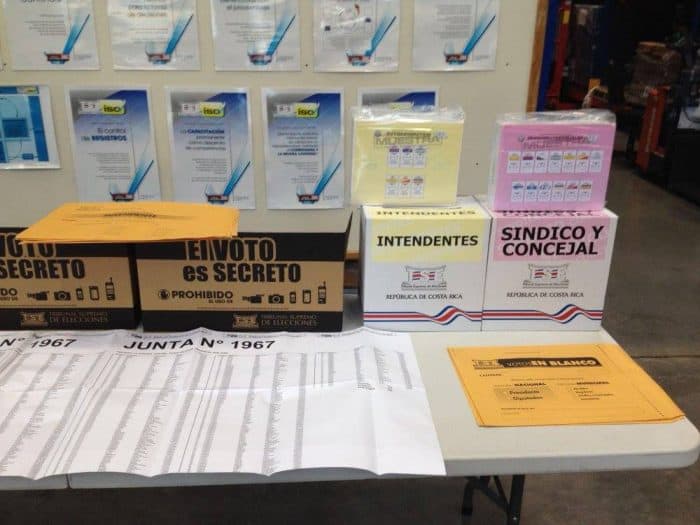

Diego Brenes, an alternate judge with the TSE, said the number of local parties registered for the elections next month has nearly doubled, from 27 in 2010 to 44 this year.

Political analyst Urcuyo said wealthier municipalities that have their own sources of income from business development have a greater motivation to organize local parties to keep more control over how that money gets spent. The blooming of canton-based parties is also the latest expression of Costa Rica’s shift toward a more multi-party political system, he said.

The TSE has been promoting the upcoming elections heavily, with billboards, radio ads, and a website with all the mayoral candidates listed by canton. But the TSE’s efforts haven’t gotten people out with banners and cheers in the kinds of demonstrations that make national elections standout events every four years.

Brenes stressed that participation in elections is ultimately the responsibility of the political parties on the ballot, not the TSE.

People say they plan to go to the polls this year, thanks or not to get-out-the-vote efforts. According to a recent survey conducted by the University of Costa Rica’s Center for Research and Policy Studies, more than 70 percent of respondents said they plan to vote this February. The number is even higher for millennials (ages 18 through 34), at 77 percent.

Urcuyo’s bar for success is far below the 180-degree reversal that the UCR survey would represent if voters act on their intentions.

“If they can improve the turnout by even five percent,” Urcuyo said, “I would consider it a success.”