The psychological impact of these events, however, has far outpaced any physical one. So far, U.S. businesses have only completed a handful of new deals. Cuba remains the only closed, one-party state in the Americas, and if anything, normalization with Washington has left communist authorities increasingly anxious about dissent and more determined to stifle it.

Cuba is still very much the same country it was a year ago. And yet, not quite.

“For a lot of my friends who are university graduates, the news was positive, and we saw it as the beginning of a long and complicated process,” said Lenier González, a founder of the group Cuba Posible, which advocates gradual reform. But for more of the population, “it produced an unrealistic expectation that things would move faster,” he continued.

“And then there are others whose hopes have run out after 25 years of economic crisis. They saw it as a good thing too, but they still want to move to Miami.”

That third group of Cubans heard in Obama’s words last Dec. 17 a cue to flee. They fear normalization will put an end to the immigration rules that essentially bestow residency and welfare benefits on any Cuban who reaches U.S. soil.

As many as 70,000 Cubans have left for the United States in the past year, in what appears to be the largest wave of migration from the island in decades.

Related: ‘Dusty-foot’ Cubans forgo rafts, choose land route through Costa Rica

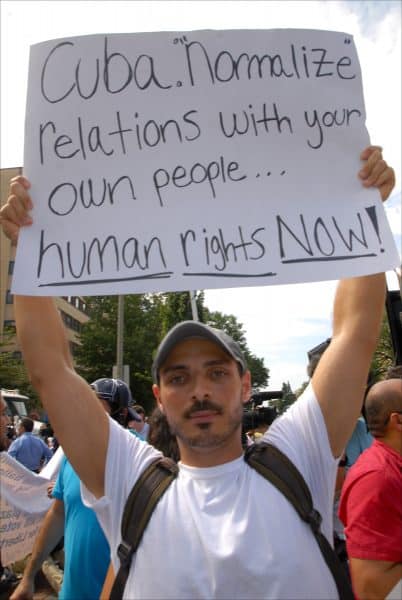

Dozens, even hundreds of activists are detained or arrested each Sunday, when the Ladies in White dissident group attempts to march in Havana and another group, the Patriotic Union of Cuba, stages a weekly mobilization in Santiago, the island’s second- largest city.

Though the government generally no longer locks up dissidents for long prison terms, it increasingly relies on short-term arrests to block protests by activists it considers “mercenaries” at the service of foreign interests.

The illegal but tolerated Cuban Commission of Human Rights and Reconciliation tallied 1,447 political arrests or arbitrary detentions in November, the highest monthly total in years.

In an interview published Monday, Obama said that the United States would continue to support Cuban rights activists and that he was considering a trip to the island – but on the condition that he can meet with dissidents. “If I go on a visit, then part of the deal is that I get to talk to everybody,” he said, in an interview with Yahoo News.

“Our original theory on this was not that we were going to see immediate changes or loosening of the control of the Castro regime, but rather that over time you’d lay the predicates for substantial transformation,” said Obama, whom surveys show is a widely popular figure on the island.

Cuban officials this year have tried to push back at public perceptions that Obama is a friend and the United States is no longer a threat or a foe. Relations will not be truly normal, they insist, until Washington lifts its trade embargo, closes the U.S. Navy baseat Guantanamo Bay and makes reparations for a half-century of economic sanctions and other grievances.

Yet the rivalry has morphed from hostile confrontation into something more sportsmanlike: a low-intensity contest to set the pace of change, with Washington trying to move faster and Cuba preferring slow, cautious steps.

As Rafael Hernández, editor of the Cuban journal Temas, put it: “We’ve traded a boxing ring for a chess board.”

Raúl Castro, 84, has pledged to step down in February 2018. Obama has 13 months left in office. That leaves a narrow window for the two men who charted the normalization course to see it through.

Rarely does a week go by without some new chess move. The Obama administration in May took Cuba off the list of state sponsors of terrorism, paving the way for the countries to formally reestablish diplomatic ties in July.

The two countries have signed new agreements on environmental cooperation. They’ve enhanced anti-narcotics enforcement. Direct mail service is set to resume on a trial basis. U.S. and Cuban officials have even started discussing their oldest grievances, opening negotiations to settle billions in U.S. property claims and Cuban counter-claims.

The U.S. secretaries of agriculture, commerce and state have all visited Havana in the past year, along with dozens of U.S. lawmakers, adding up to the highest-level government contacts in decades.

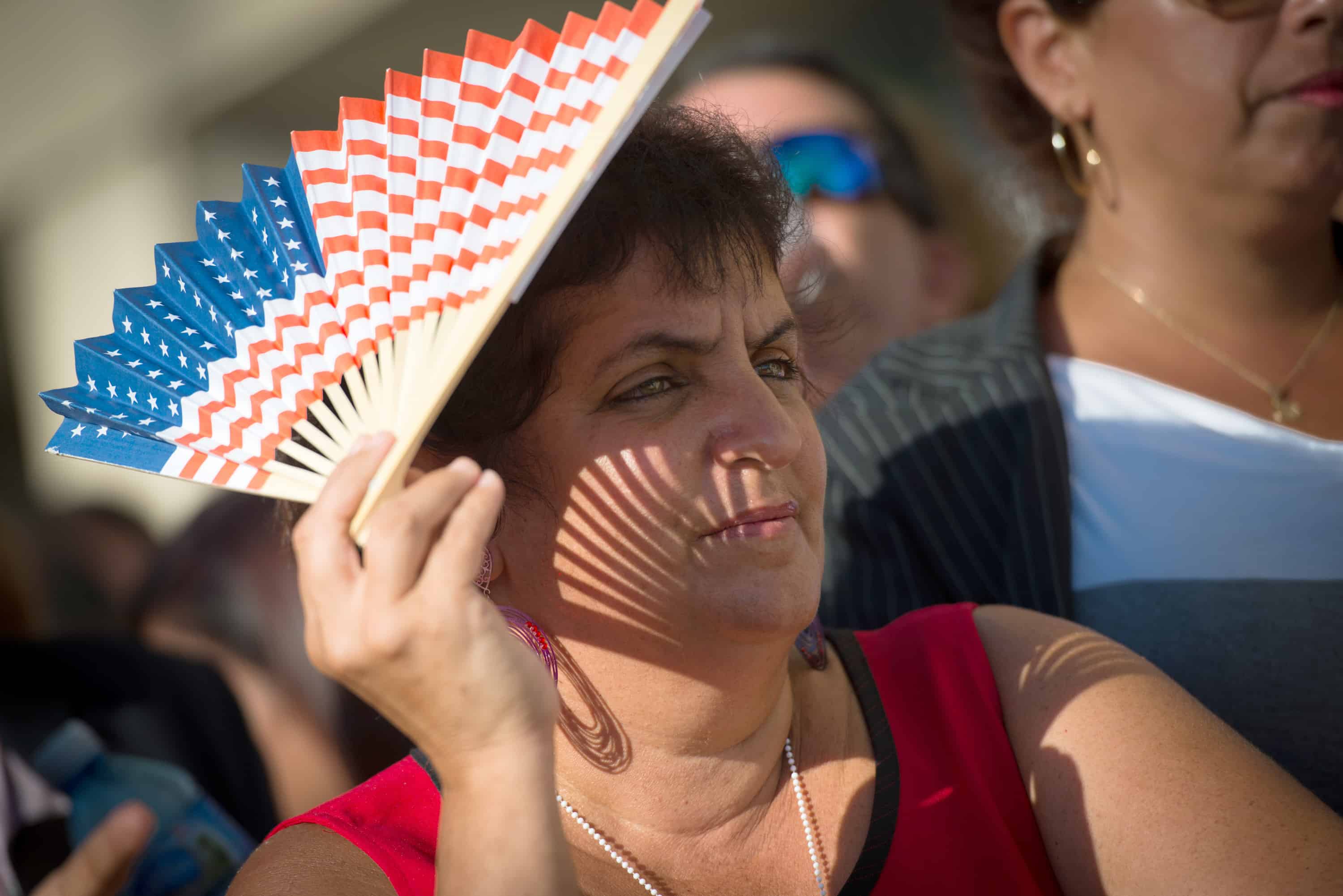

A U.S. tourism tsunami still seems to be building. U.S. travel to Cuba increased by 40 percent since last December, according to industry estimates. Overall tourism to Cuba increased nearly 20 percent, bringing billions in additional revenue for the government.

“Our booking activity has been off the charts,” said Tom Popper, president of Insight Cuba, the largest U.S.-based provider of the licensed “people-to-people” travel permitted under U.S. law.

Most of the U.S. travelers have come to Havana, where a shortage of hotel beds has kicked off a scramble among Cubans and their foreign business partners to buy, renovate and rent properties. Each city block seems to have at least one crew of contractors patching cracks and applying paint.

A deal to reestablish regular commercial flights between the two countries is said to be imminent, with United, JetBlue, American Airlines and other U.S. carriers pledging to begin service as soon as they’re cleared by the two governments.

Cuba established a direct phone link with a U.S. company, IDT, and a roaming agreement with Sprint. It has set up nearly 50 outdoor WiFi hotspots at parks and boulevards across the island, where Cubans gather round-the-clock to chat with friends and relatives overseas.

But the initial Cuba excitement among U.S. companies has been replaced by something more “sober” a year later, said James Williams, president of Engage Cuba, a group lobbying to lift the embargo.

Williams said he knew of at least two-dozen U.S. companies that had submitted formal business proposals to the Castro government, aimed at taking advantage of more flexible rules. “I would imagine it’s probably in the hundreds,” he said.

The companies want to lease office space, build warehouses, dock cruise ships and ferries. Not one has gotten a green light so far, he said.

“Frankly I think the Cubans have been overwhelmed with a surge in interest and the decentralized nature of how that interest is coming to them, with companies calling them up, consultants coming to them, and not a lot of clarity about how to make a deal,” said Williams. “The non-responsiveness has slowed things down.”