On Wednesday, Nov. 11, the Artflow Gallery inaugurated a three-part art exhibit inauguration by Costa Rican artists Carlos Poveda and Pablo Romero and Cuban artist Jairo Alfonso.

Renowned artist Poveda, 75 years, presents his audience with a contemporary artwork series made out of materials disposed of by various companies: plastics, metals, polyethylene, and polycarbonate. Poveda has studied in San José, Cartago, the United States (Printmakers Workshop, Washington D.C.), Poland (Lodz University) and England (Camden Arts Centre, London), and now lives and works in Paris. His work has received awards such as Sao Paulo’s Art Biennial and Costa Rica’s Aquileo Echeverría Prize for drawing.

Emerging artist Romero, 25, demonstrates satirical humor and a critique of Costa Rican society through collage. A onetime law student at the University of Costa Rica (UCR), he switched to Visual Communication with an emphasis in Painting at the National University (UNA). He has participated in various collective and individual art exhibits around the country.

The perspectives of these two artists differ, yet they share an ironic perspective and interest in social crticism. The Tico Times sat down with artists Poveda and Romero, who did not meet before this project, at the Artflow Gallery in the San José suburb of Escazú. Excerpts follow.

What does the word art mean to you?

CP: I’d say it represents, besides a historical fact, a historical feeling that is demostrated to the creating artist. It represents an investigation. That word for me is fundamental. Art is something that is born from your heart. It’s not something that you invent.

PR: I agree with Poveda. I’d say it’s a path, something very personal. I try to work based on my personal concerns. The word art is a bit conflictive for me. I’m not sure if what I do is art or not, and I’m not very concerned about it, but I’d say it’s a path.

Which is your favorite medium?

CP: That’s something difficult to decide. I’ve been through three phases. I began drawing and discovered textures; these textures can now be seen in my photography of the plates. Color is not my forte. I never studied color… I work a lot with companies’ plastic or metal wastes. I prefer to have the material discover me. There’s a communication from artist to producer and from the object to the material. It’s fantastic!

PR: I also have an affinity for drawing. I practiced since I was a child. When I become more conscious of the process, thanks to art school, I’ve became more involved with the collage technique. There’s something about the recovery of images from different media that I feel has nothing to do with the artistic part. There’s a progression and exploration from that idea of the collage. There’s also a part of what is found. With the collage technique there’s this random factor. If you’re looking through a series of images, you find something that draws your attentio: you cut it, and keep it. It’s a very random thing. I’ve also discovered this in the found paper. There’s a romp or flirtation between the dimensional and tridimensional.

CP: In this aspect we’re very similar. It’s funny that we didn’t know each other until now.

Why did you choose to become artists?

CP: I don’t know if you can categorize me as an artist; I’m more of a producer. Since I was a child I had an affinity for creating things with my hands. When I was 7 years old my teacher would tell me to draw on the board. I had an innate ability. [Later] I read in La Nación about a contest to design Costa Rica’s editorial logo. I participated and won. The logo is mine and they’ve modified it several times, but it’s the same design. That’s where I started getting involved as an artist. I found myself working with a pharmacy distributor. I had certain skill and the owner asked me to create a shop window. I then created pop art without realizing what I was doing.

There’s also the luck factor. One day while wandering through the streets of San José I entered Las Arcadas building and there was an exhibition by Grupo 8. For the first time I realized I had a love for abstract and figurative art. That mixture of things, of modern art made me crazy! [Artists] Harold Fonseca and Rafael García came by and asked me what drew my attention. I began talking to them and told them I drew, so I brought them the drawings the next morning. The next day I got a phone call from them to go back to Las Arcadas; eventually, they invited me to participate with them at an exhibition in Washington. My first drawings got sold there. I went to the U.S. and my career began there. It’s luck. I was invited in the precise moment. Now I’ve been introduced to this new, young artist!

PR: It’s not something you decide. Personally, I don’t consider myself an artist. That’s the job for others to determine. Especially in the art world, it’s a very complicated thing. There’s a power struggle among [the entities that] decide what’s art and what’s not.

In my case, as with Maestro Poveda, since I was a child I felt that sensitivity for creating thing with my bare hands, for colors, but I had a bad experience with art. While I was at the UCR as a law student, I rediscovered that enjoyment toward working with my hand,s drawing, painting… and I got into art school. I was very naïve about positioning yourself in the market, but here I am, beginning. It’s been a blind path. It was not well thought out, and it’s a path that has been building up.

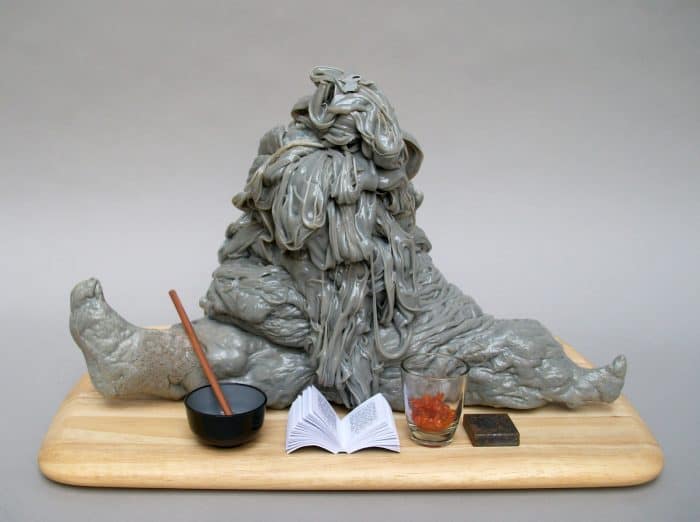

![S/t by Pablo Romero. Mixed media. [Courtesy Artflow Gallery]](https://ticotimes.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/S.t.3-ed-681x600.jpg)

CP: When you find or search for an object, which is your relationship or feeling with that object?

PR: There’s something about waste: They’re objects that have a story. They had a specific use and were forgotten, discarded. Most of the time they have a time signature. They’re not the same thing they were at the beginning. Someone has already touched those objects and that’s what really seduces me. A new object, newly bought, does not speak to me, but an object that has a story within it is what makes a click within me.

PR: I find it really interesting this thing about the food plates, your still lifes. They remind me a bit about the vanitas, which speak a bit about life and death through food, through foods that are often pompous and elegant. What is your intention behind these objects?

CP: It was born out of a joke. I was in my workshop in Caracas in the year ’95 or ’96. I was very focused on making trees out of plastic wastes. I had various elements such as seeds, ojos de buey, chumicos, wire, and all sorts of stuff like that, and I was making trees on the table. My wife then called from the first floor of the house and told me her sister, Diana, was coming home with a beautiful gift. She’d brought her an Alessi plate. It was beautiful, black matte with dazzling designs! I was very concentrated on what I was doing. She climbed up the stairs and left the plate there for me to see it. I was rude to my wife. I didn’t even tell her it was beautiful and thank her for bringing it. As a joke, I took some black and white plastic pieces, chumicos, and ojos de buey, and told her “Raquel, come! Look at my first still life.” The next day a collector came and asked me what it was and I told him it was a still life. That’s the story. It came up as a joke and it still is a joke, but an artistic joke because I’m confronting a geometric element with an expressionist one.

Our “Weekend Arts Spotlight” presents Sunday interviews with artists who are from, working in, or inspired by Costa Rica, ranging from writers and actors to dancers and musicians. Do you know of an artist we should consider, whether a long-time favorite or an up-and-comer? Email us at kstanley@ticotimes.net.