PUNTA LEONA, Puntarenas — The press covering the 11th Latin American Congress of Private Nature Reserves had to get up a half-hour earlier than everyone else Wednesday to be at breakfast at 6:30 so the bus could leave at 7. We being journalists, we showed up for breakfast at 6:20. And this being Costa Rica, the bus left at 7:30, when all the other buses were supposed to leave.

This delay would keep us racing all day — although there was time for one breakfast, two snack breaks and one lunch with coffee, dessert and dancers. We were served watermelon, pineapple and papaya no fewer than three times. A monkey would have loved this junket.

But I’ve buried the lede — at a news conference upon our return to Punta Leona, Paraguay was announced as the venue of the next biennial congress, in 2017. I hope they have lots of papaya in Paraguay.

Also, we were introduced to the five newly elected directors of the Latin American Alliance of Private Nature Reserves, in which Martin Keller of Guatemala would once again serve as president, while Costa Rica’s Rafael Gallo, founder of the whitewater rafting company Ríos Tropicales, would be treasurer (“with no money,” he quipped), along with other directors from Colombia, Nicaragua and Chile.

Also, thanks to a donation of 200 hectares of protected forest from Ríos Tropicales, the alliance would be ponying up an estimated 3,600 tons of carbon credits for commercial trade. Carbon credits are a little hard to understand but are apparently extremely important for saving the planet.

“It’s a pilot program to incentivize the sale of carbon credits,” said Keller. “With this we’re initiating a sustainability strategy with a view to turning ourselves into the most important private conservation organization in the world.”

But enough about saving the world, and back to the tour. After the press caught up on its sleep on the bus, we arrived at Playa Matapalo, south of Quepos, where we visited a turtle nursery (where we saw neither turtles nor turtle eggs, but it was very educational).

Mariana Alvarado, speaking for the Association of Volunteers for the Service of Protected Areas here (ASVO-Playa Matapalo), said the staff patrols 8km of beach every night from about 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., looking for tracks left by turtles, mostly olive Ridleys.

“When they see signs of sea turtles, there’s a race between the people who want to steal the eggs and us,” she said.

When the volunteers find a nest where a turtle has laid her eggs, half the time they dig up the eggs and bring them back to the nursery. The other half of the nests they camouflage to try to protect them from hueveros (egg poachers).

“We don’t brings all the nests we find,” she said. “Why not? Because there has to be an equilibrium. There’s a natural cycle that the turtles have here on the beach, and from the time we remove the eggs, we’re breaking that equilibrium. So when we bring them here, we try to make the least impact possible, to be as careful as possible with the handling until we make the nest, as close as possible to the way the turtles do.”

Back at the vivero (nursery), the eggs are buried in the sand, with every effort made to replicate a natural turtle nest.

“We’re always working to improve our techniques, because we know we’re never going to make a nest exactly like a sea turtle does, but we can make it similar,” Mariana said.

Each nest is surrounded by a little plastic pen, in an enclosure with a chest-high plastic fence. There are currently about 50 nests here. Guarding them is a 24/7 operation, to keep out not only hueveros but hungry monkeys, vultures and other predators.

The sand around the eggs is occasionally stirred to aerate it, to reduce the growth of microorganisms and to mitigate the hardening of the sand after rains.

The eggs take about 45 days to hatch, and the hatchlings scamper to the sea. About 5,000 turtles are saved in this way every year, Mariana said. (Many, of course, are killed by predators in the ocean, but that’s outside ASVO’s jurisdiction. Out of 1,000 sea turtle eggs laid anywhere, it’s estimated that one turtle survives. This is why turtles have lots of sex and lay lots of eggs.)

By now we were already running late, so when we made a bathroom stop at the ASVO facilities we were asked to go only if we really needed to go. It’s not easy being a journalist.

The next stop was Hacienda Barú, a 330-hectare biology research center and ecolodge with 7km of walking trails, an orchid garden and a butterfly garden. After the obligatory watermelon, pineapple and papaya refrigerio, proprietors Jack Ewing and Steve Stroud told us about the origins of this place in U.S.-accented Spanish.

Jack said when he first came here in 1972, the government was encouraging people to cut down forests and put the land to work, grazing cattle and growing coffee, bananas and rice. Tourists were few and far between.

Jack said in the mid-1980s some Swiss friends of friends came to visit, and he took them on a three-hour hike through the rain forest, one of the most biodiverse habitats on the planet. The Swiss visitors were wowed, and a woman asked him how much they owed him for the tour. He said nothing, it was free.

The woman said he must accept something for such an extraordinary experience, and she stuffed two $20 bills in his shirt pocket and kissed him on both cheeks. (The journalists laughed.) A light bulb went on over Jack’s head. He realized that he could get paid for doing his favorite thing, walking around the rain forest.

“And if I’m lucky,” he said, “I’ll get kissed on both cheeks.” (The journalists roared.) Jack started offering paid tours, and made $300 the first year, 1987. The next year, he made $300 in January alone, and $1,500 for the year. The next year, he made $1,500 in January alone, and so it went. Ecotourism in Costa Rica had arrived in a big way.

Today the Barú National Wildlife Refuge gets about 18,000 visitors a year. It employs four guardabosques, rangers who patrol the park collecting scientific information and educating locals about conservation more than trying to be cops busting bad guys.

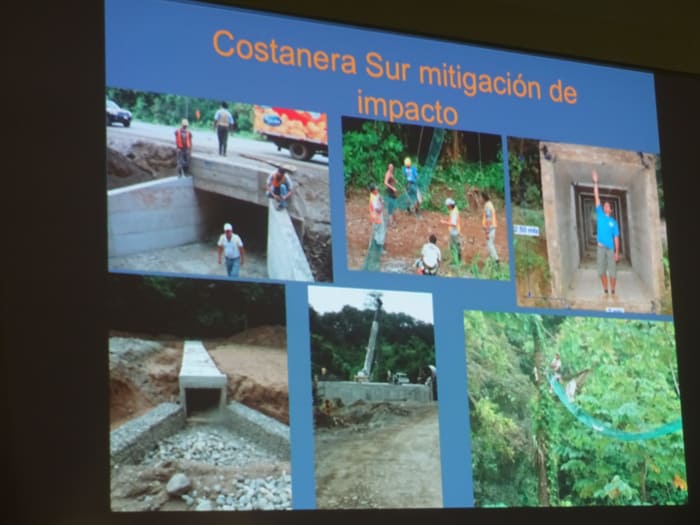

One of Barú’s accomplishments during the construction of the Costanera Sur coastal highway was to persuade the government to build 29 passages under the road for animals to cross safely. In the old days, the road was so bad that cars had plenty of time to stop if a sloth was crossing the road at glacial speed, but the new highway would be fatal for many animals. Today sloths, pumas, agoutis, monkeys and anteaters have been filmed using the underground passages.

Hacienda Barú also spearheaded the building of rope/mesh bridges over the highways for monkeys and other arboreal animals to cross safely. It took the monkeys a while to try them, but once the first monkey crossed, well, monkey see, monkey do.

After this presentation, we were seriously atrasados (running late), so we had only 10 minutes to explore the trails at Barú, as our timekeeper, Guillermo Piedra, insisted to tour guide Carlos Jiménez. What can you see in 10 minutes?

It took Carlos five minutes to find a three-toed sloth dozing in a tree — close to the ground and easy to see.

That left Carlos enough time to answer one of my biggest questions about Costa Rican wildlife — why do sloths come down from trees only to take a crap, once a week? He said it was because if they scatter-shat from the trees, pumas and other predators would smell them far and wide. They descend to the ground to take a discreet dump for their own safety.

I’m still waiting for someone to tell me how a large mammal manages to defecate only once a week. And we were off, back to our air-conditioned bus for the short ride to Portasol, a sustainable real estate development in Portalón, between Dominical and Quepos. But that story will have to wait for another day, because I’m a hard-working journalist and I have to take a break.

All that watermelon, pineapple and papaya doesn’t just eat itself.