NEW ORLEANS, Louisiana — Upstairs in the house at 1907 Jourdan Ave., it’s as if the levee never burst. Kids are rolling through jazz standards on saxophone, trumpet and trombone, sneakers tapping. They sway some and, on a sweet note, their eyelids fall heavy.

Outside, though, the music floats into emptiness. The house stands alone as darkness falls on vacant lots with waist-high weeds, a toppled basketball hoop, a front walk that leads nowhere. Even the children playing jazz are outsiders, driven here by parents who live somewhere else.

Ten years after the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, the Lower Ninth Ward is still largely lost.

While the rest of New Orleans has regained about 90 percent of its pre-Katrina population, only about a third of properties in the Lower Ninth have been repopulated — some by newcomers unfamiliar with the traditions of the storied neighborhood that gave birth to members of some of the city’s premier brass bands.

“It’s kind of drab now,” said Velma Collins, 73, a retired federal worker who remembers a lively place full of music, working families, shared meals and open doors. “You just don’t have anything to do anymore.”

A tangle of factors explains the slow recovery: Battered by a catastrophic surge of water when the levee burst, the Lower Ninth suffered more severe damage than other parts of town. City officials struggled to restore basic services, and residents were forced to wait more than a year to return. Even then, many low-income residents found that the federal program created to help homeowners would provide them enough to relocate but far too little to rebuild.

Before Katrina, 17 families lived on the block bounded by Jourdan Avenue to the west, Johnson Street to the north, Deslonde Street to the east and Prieur Street to the south. The block lies beside the levee, and its geography is dominated by it.

Basically a hill topped by a concrete wall, the levee is supposed to protect the area from a shipping channel known as the Industrial Canal. When the levee burst on Aug. 29, 2005, all 17 homes were swept from their foundations.

Since then, eight homes have been rebuilt. Newcomers have moved into four. And of the original 17 families, four have come back home.

There’s Collins, an avid gardener who complains that flowers will no longer grow in the poisoned soil. She no longer knows her neighbors; her niece and her children have moved to Texas.

There’s David Hale, a seaman, and Don Cunningham, who bought a house across the river in Gretna, but ultimately decided to return to the Lower Ninth.

And there’s the Allen family, whose son, Shamarr, is an acclaimed trumpet player. Shamarr Allen, 34, grew up in the Lower Ninth Ward, learned to play music here and is trying to rekindle the rich traditions that nourished his career.

Once a week, Allen returns to his parents’ rebuilt home at 1907 Jourdan and holds free music lessons on the second floor. This night, he is coaxing a solo from a timid 10-year-old with a buoyant enthusiasm.

Come on, Allen tells the boy: “You’ve been waiting for this moment your whole life!”

—

In a narrow sense, a neighborhood is just a collection of houses. But the old Lower Ninth registered as more than that. It was a place of long-standing personal connections and traditions, and it played a role in the distinctive culture of New Orleans.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the area’s ability to nurture musicians. At least one bona fide legend was living in the Ninth when Katrina struck: Fats Domino, the now-elderly pianist who recorded “Ain’t That a Shame” and “Blueberry Hill.”

But the Ninth’s musical heritage was far richer, studded with local heroes. Kermit Ruffins and Keith “Wolf” Anderson, neighbors to the Allens, developed solo careers after stints with the renowned Rebirth Brass Band, a New Orleans institution founded in 1983. Bennie Pete, founder of the Hot 8 Brass Band, lived in the Upper Ninth, while the band’s drummer, Dinerral Shavers, came from the Lower Ninth.

Shamarr Allen has played with Harry Connick Jr. and Willie Nelson.

This density of celebrated musicians wasn’t happenstance. The place cultivated musicians, little kids playing horns and drums, the community celebrating its high school band, each generation of musicians passing their experience onto the next.

As a child, Allen said he would sit on the front porch or up on the levee for hours practicing new songs, and Ruffins or Anderson would come by, offering pointers.

“It was all hours of the night, man,” Allen recalled, “and nobody ever said, ‘That’s too loud.’ ”

—

Among outsiders who watched on television as Katrina struck and the Allens’ desperate neighbors were plucked from rooftops, the Lower Ninth looked like a poor and lawless place, a place from which everyone was frantically trying to escape.

But the reality was different. Yes, there was crime and drugs before the storm, but more than half of residents owned their homes. Most worked, and many had extended families — aunts, uncles, parents, grandparents — living just a few blocks away.

On the Allens’ block, there was a longshoreman, a carpenter, a security officer, a chemist for the state, a sandwich shop manager.

The Lower Ninth “was a little world unto itself, a sit-on-your-porch, trade-vegetables-over-the-fence, have-Sunday-dinner-with-your-grandmother kind of place,” said M.A. Sheehan, director of a nonprofit group that seeks to help residents return.

“People say, ‘Well, it’s 10 years later,’ and they’re not back yet. They must not want to come back,” Sheehan said. “But I have people sitting in my office crying because they want to come back.”

Of 2,100 homeowners in the Lower Ninth who qualified for federal aid after the storm, two-thirds said they wanted to rebuild. On the Allens’ block, four of 17 came back home. Two others returned to the neighborhood but now live on different blocks. The Washington Post was able to contact 10 of the remaining 11 families. So far, none have plans to return.

Most said they would have liked to come home, but they cited a litany of barriers, starting with the city’s long delay in making the Lower Ninth habitable again.

For more than eight months after the storm, city officials prohibited residents of the Ninth Ward even from returning to their properties. Basic services such as drinking water weren’t restored for more than a year. While people streamed back into the Bywater and Treme, the Ninth Ward remained ruined and silent.

Deborah Weber, 55, was among those who wanted to return. A former chemist with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, Weber loved the “Lower Nine.”

“It was a nice place to live, a family atmosphere,” she said. “We left the door open. We knew everybody. … We’ve always wanted to return.”

Weber weathered Katrina with her family in Shreveport. But after months away, she had to get back to work.

“We needed a house,” Weber said. Her old one was gone. And “there were even some people saying maybe the Ninth should never be rebuilt.”

So Weber’s family decided to buy about 10 miles away in New Orleans East. Their new neighborhood is pleasant, she said. The people are generally wealthier, and the homes are generally bigger. But so is the distance between them.

“Here, I couldn’t even tell you my neighbors’ names,” Weber said.

Weber received $50,000 in federal homeowner’s aid — a sum that helped in the purchase of her new home but that would have been too little to build from scratch in the Lower Ninth.

It was a common problem in poor, black neighborhoods: The maximum payment available to any applicant was equal to the market value of his or her destroyed home. For people with small, wooden shotgun houses typical of the Lower Ninth, there was often a yawning gap between the home’s market value and the cost to rebuild it.

While rebuilding might cost upwards of $200,000, Sheehan said, the market value of many homes in the neighborhood was probably no more than $60,000. Other grants could boost the payout under the Road Home program. Still, federal checks written in the Lower Ninth were, given the damage, significantly smaller than those handed out in other neighborhoods.

The delays in restoring utilities and in launching Road Home would prove decisive for many former residents. Even families with the means and the desire to rebuild sometimes chose not to, fearful that the reconstructed levee would not hold.

Darron Burton, 49, remembers playing up on the levee when he was small and noticing that the passing ships towered over his house far below.

“You would look at the water and then look back at the land, and you’d go ‘whoa!’ The water level was higher than the street! I was always a little scared,” Burton said. “Every year, you’d have hurricanes and you’d wonder: ‘What if? What if that levee broke?’ ”

When the unthinkable finally came to pass, Burton’s childhood home was washed away. His parents recovered just $5,000 from homeowners’ insurance. They were savers, so they had money to rebuild. But they opted to do it in Baton Rouge, mainly because Burton’s mother was afraid.

Once resettled, Burton’s father seemed depressed. Every few days, the retired longshoreman would hop in the car and drive the hour and a half down Interstate 10 to his old lot, where he would sit on the slab and talk to whomever was around.

In July 2006, less than a year after Katrina hit, William Burton died.

“The doctors say different, but I believe he grieved himself to death,” Darron Burton said. “Everything that was familiar to him was taken.”

—

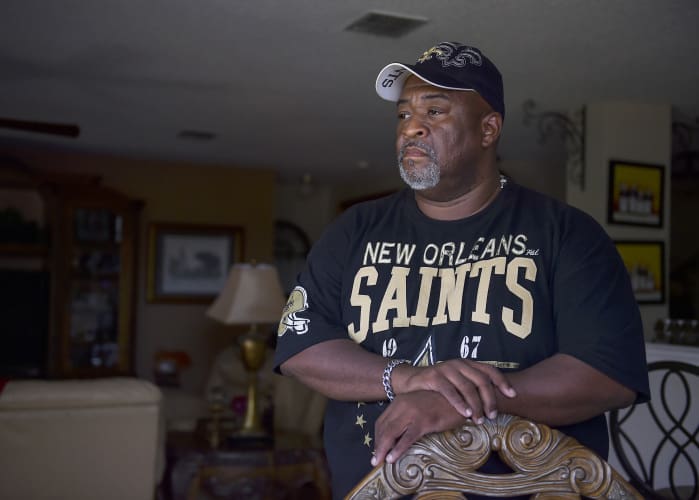

Keith and Sharon Allen weathered Katrina with Shamarr’s younger siblings in Oklahoma City. They stayed for more than a year and felt welcome, Keith Allen said. But they also felt homesick. They bought a huge mural of people sipping champagne at a jazz club while a soloist wails on the sax to remind them of home.

“There was nothing like getting back to New Orleans,” Keith Allen, a 60-year-old carpenter, said. “You know how they say, ‘It takes a village?’ That’s what we had here.”

Shamarr had been living elsewhere in New Orleans when Katrina struck. He evacuated to Atlanta but was determined to return.

“If all of us decide, ‘I’m not going back,’ there’s a big old gap,” he said. “And all the out-of-towners will come in and change the sound of New Orleans music.”

Two years ago, Shamarr Allen came up with the idea of free music classes. His parents insisted that he use their house. He sees potential in all his students. Luis Jahuey, 12, already earns as much as $800 a day busking on the tourist-packed sidewalks downtown.

On a recent Tuesday, the youngest of Allen’s students was 10. The oldest, Utopia Francois, was 14, her yellow hoop earrings spinning as she rocked her saxophone. Allen put them through their paces, barking instructions: E flat! D! C sharp!

“If you can’t play it slow, you can’t play it … ?” he questioned.

“Fast!” they shouted back in unison.

Blowing the trumpet one-handed, Allen snapped the fingers of his other hand in time to the music. When the session was over, he hugged each child before they climbed into their parents’ waiting cars and drove away.

The noise of their engines faded to nothing.

Left alone in the silence, Allen said he is cautiously optimistic about the future. The Lower Ninth, he noted, has been “untouched by the gentrifiers,” who have descended on other parts of the city. Many lots, though vacant, are still owned by the same families who used to live here. One day, he hopes, they will scrape together the money to rebuild.

When they do, Allen will be waiting.

“You need to be home, passing on the tradition,” he said. “Even if it’s just one person or two people, you need to be there passing it along.”

© 2015, The Washington Post