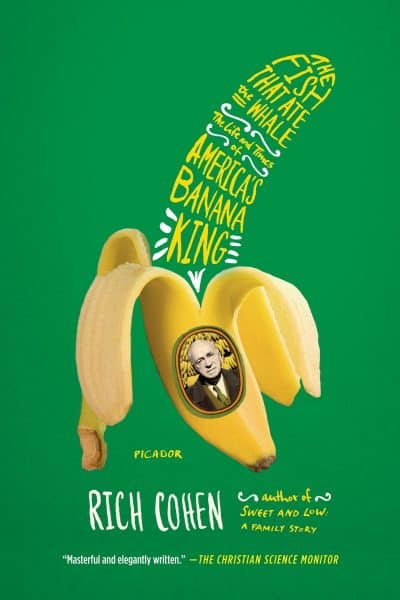

I was perusing the shelves of the Lucha Libro bookstore in Granada, Nicaragua for an interesting title about Central America when “The Fish That Ate The Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King” by Rich Cohen caught my eye. Its green cover with a half-peeled, yellow banana sporting an oval label of an elderly man in a suit and tie looked interesting. The man on the label was Sam Zemurray, the Banana King.

But who was Sam Zemurray? His might not be a household name – unless, of course, you live in New Orleans, or are a scholar of Central American or U.S. business history. Or perhaps you’d know him if you’ve study corporate greed or anti-trust, or maybe U.S. intervention in its neighbors to the south. In that case, you probably know a lot about the impoverished Russian-Jewish immigrant who eventually became the president of the behemoth United Fruit Company. He was the man who had a heavy hand in the politics and economics of Central America’s so-called “banana republics” for much of the twentieth century.

The book jacket reads, “Working his way up from a roadside fruit peddler to conquering the United Fruit Company, Zemurray became a symbol of the best and the worst of the United States; proof that America is the land of opportunity, but also a classic example of the corporate pirate who treats foreign nations as the backdrop for his adventure.”

As a young man in New Orleans, Zemurray got the brilliant idea to gather the many bananas that were otherwise delectable but slowly showing signs of ripening and thus were discarded as waste by the long-haul, big-time fruit suppliers. Taking his inventory and riding the rails while selling these bananas, he became wealthy and expanded his business. Eventually Zemurray owned vast plantations in Central America and a fleet of freighters to move his product to U.S. markets on his way to becoming the Banana King.

Cohen weaves a fascinating story of Zemurray’s exploits, his incredible business sense and his dealings with a variety of character – some rather shady and, like Zemurray himself, seemingly larger than life. Along the way, Cohen provides anecdotes. He also, sometimes a bit too heavily, throws in his own two cents about how Zemurray’s life and activities are somehow emblematic or manifested larger trends as he draws out bigger explanations about the Americas in the 20th century. Cohen may be correct in those grandiose comparisons, but perhaps it is best to leave such musings up to the reader.

Zemurray was a tough Jew, a very tall and big man physically. He was a street-smart immigrant who spoke with an accent and took big risks. Unlike most of his counterparts at his level, he traveled throughout Central America, learned to speak at least some Spanish and understood the business from the treetops down.

Throughout this whirlwind of a book about a whirlwind of a life, Cohen teaches the reader about bananas, Central American politics and history, and the Banana King’s role in the turbulent politics of Honduras and Guatemala in particular. He was also a major contributor to Tulane University, whose president’s official residence to this day is Zemurray’s former home. Among other things, Zemurray funded New Orleans’ first hospital for black women, established a clinic for troubled children, and worked to preserve Mayan ruins.

The real and full account of his charitable and perhaps not so honorable pursuits may never be known. Zemurray’s life touched upon the rather illustrious Louisiana Governor Huey Long, the establishment of Israel and even the infamous and disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, each in ways that might be rather unsavory, as Cohen hints at, but wisely does not draw conclusions. Throughout, Zemurray tried to keep his distance, to keep his hand invisible and not garner publicity.

When it comes to the critical point when late in life Zemurray surprisingly and almost instantaneously wrests control from the Boston Brahmin rulers of United Fruit, Cohen makes it seem as if the reader were in the corporate boardroom. I won’t spoil that for the reader.

The elderly and weary Zemurray seems never to have been a happy person. Despite having read this exceedingly worthwhile book, I still find it hard to really understand who Zemurray was and what motivated him, as he was clearly highly motivated. Cohen probes into Zemurray’s life and character, sometimes perhaps bordering on psychiatry. Even so, this reader never really got more than a glimmer into the mind of a man who seemed a tragic figure, despite amassing great wealth and wielding power and influence both in Central America and the United States, and perhaps to a certain extent on the world stage as well. Those unanswered questions about the man may not be a shortcoming of the author as much as it is a statement about the subject himself.

Suffering health setbacks, the debilitated Banana King died in 1961 at the age of 84 and with a fortune worth $30 million at the time. The Associated Press obituary said that, “In the banana belt of the Caribbean, Sam Zemurray was known as ‘the fish that swallowed the whale.’ ”

“The Fish That Ate The Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King” by Rich Cohen. Picador-Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.