The boat skidded across the bay. The bow sliced easily through the placid water, and spray dovetailed on both sides. The town’s rooftops receded into the distance, until the mangroves devoured the horizon. The ocean water was a blend of different blues – turquoise and iris and viridian – that washed over each other, pointillist landscapes of tiny waves.

Over the buzz of the outboard motor, I could hear Freddy and Miguel shouting to each other. It sounded like casual conversation between two diving instructors, but I couldn’t understand a word. The two men were born and raised in Panama. They were both Afro-Caribbean, dark-skinned and sturdily built. They had known each other their entire lives.

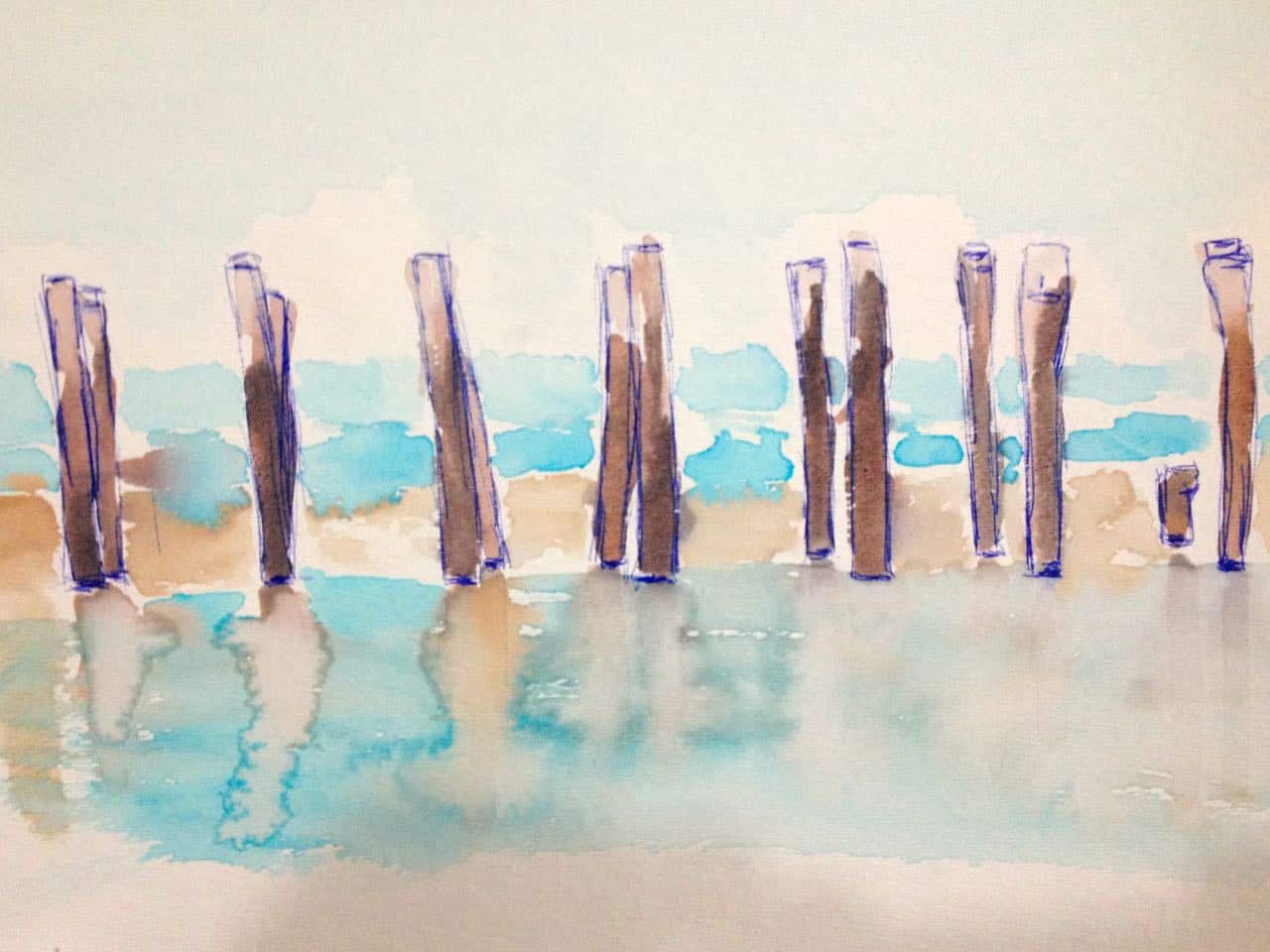

Miguel cut the engine, and the boat came about. Several wooden posts jutted out of the water, the remains of an old dock. As Miguel throw a line around one of the posts, I asked Freddy, “Was that patois you were speaking?”

He grinned vaguely. “Yes, that was patois.” I waited for something else, some commentary about the language and its history, but Freddy only said, “Okay, now we will do your first open water dive.”

As I fitted my fins and dragged my BCD and air tank to the edge of the boat, Freddy outlined what we would be doing: We would dive to about 15 meters, kneel on the ocean floor, and practice some basic maneuvers. I would release and retrieve my regulator, clear water out of my mask, and establish buoyancy.

Freddy spoke in a slow and deliberate voice, like the instructional videos I had seen back at Starfleet headquarters. He sounded as if he had memorized every word of the textbook, so that he could deliver its instructions rote. I wasn’t surprised, given Freddy’s many years as a diving instructor. He had probably taken more landlubbers like me into the depths than he could count.

“Then we will see the wreck,” said Freddy.

“The what?” I asked, startled.

“A shipwreck. There is an old ferry down there, and we will see it.”

“Oh,” I said. “Well, great!”

As Freddy lifted the BCD onto my back and I fastened its clip and Velcro, I wished I could explain how excited I suddenly was. Yes, we were diving in open water, which was invigorating enough. But a wreck! Sunken ships and artificial reefs had captivated my imagination since my earliest years. I had little interest in deep-sea diving or spearfishing or underwater caves, but I yearned to explore a shipwreck. I couldn’t believe how quickly we were moving – it was only the second day, and already a lifelong fantasy would be realized.

I leaped into the water, then bobbled on the surface as Freddy jumped in beside me. We kicked our legs, drifting backward toward a bright buoy. Freddy took me through the steps of descent – signaling, looking around, checking the time – and then we pressed a button and released the air in our BCDs.

These first few seconds were always the strangest, sinking below the surface, feeling the pressure build in my temples. The warm water cooled, and I felt the slightest current, like a liquid breeze. My eardrums crackled noisily, and I struggled to normalize, pinching my nostrils and blowing out. The sound was like the squeal and crunch of breaking Styrofoam, but each time my sinuses felt better, until we had reached the sabulous floor.

Recent rains had turned the water murky, but I could still see Freddy clearly. After some basic exercises, Freddy tilted his hand sideways. Maintain buoyancy.

I lay face-down in the silt, then pressed a button, sending a shot of oxygen into the BCD. I took a deep breath, and just as Freddy had predicted, my body started to levitate. My legs and torso remained horizontal, but I lifted off the ground, genie-like. Then I exhaled, spouting bubbles. My body then fell again, but not low enough to touch the firmament.

Freddy tapped me on the shoulder and made a ring with his fingers. Okay?

I did the same. Okay!

He shook my hand.

Buoyancy was a new concept to me, and I had never really noticed how divers move. Their bodies remain prostrate, and as they kick their fins, they often clasp their hands over their stomachs, like meditating monks. I had seen this posture a thousand times in photographs and movies, but I had never considered its significance.

Such buoyancy isn’t just a skill, but a sign of maturity. Experienced divers know how the air inside their lungs will affect their depth. In a three-dimensional space, where every meter adds or removes pressure, and breathable oxygen compresses and expands inside your body, buoyancy is an art. Every breath matters.

We swam over a rise, and the wreck emerged. The old ferry was a man-made hulk, linear and rigid. But nature had reclaimed its surfaces: Coral and plants encrusted the exterior, and schools of fish darted synchronously around its frame. I saw a half-dozen other divers, who glided over the oceanic garden, looking as mesmerized as I felt. The water was shallow but hazy with plankton, and the blend of light and mist lent an ethereal atmosphere.

Ever since my first dive, I have relished the sight of marine life. When Freddy gestured to a trio of squid, they looked like transparent violins, their bodies vibrating nervously as they hovered around an old mooring chain. When Freddy spotted a stingray, I nearly forgot to breathe; the cartilaginous fish is an icon of the scuba experience, and divers and stingrays are routinely pictured together to demonstrate how exciting this sport can be. To actually see its flat body flap slowly against the ocean floor, raising clouds of silt, quickened my pulse. I had never observed such a thing in real life, and only by continuing to dive could I hope to see it again.

But as we glided over the wreck, I was reminded what I love about the seashore – not just its beaches and waves, but the decaying artifacts of human settlement. In every part of the world, people build their docks and boathouses and crab shacks. Lighthouses rise out of cliffs, and harbors become forests of sailboat masts. And yet the salty air eats away at the wood and metal. Hulls are gradually covered in barnacles.

Steel roofs turn red with rust. Every hinge squeals. Tools deteriorate in their boxes. Ropes fray and unravel. Boatyards accumulate mounds of old paddles, torn nets, broken lobster traps, and all the other detritus of maritime life. Coastal development is a lesson in futility, as planks rot and machinery crumbles. “Never buy a used car from a beach town,” my friend Beto once advised. “It will fall apart in no time.”

I love what the ocean does to human objects, making them sag and sink, crack and fleck away, until everything looks aged and decrepit. This is the world of Winslow Homer, moist and ever-changing, where every hook and rowboat succumbs to age and elements. The ruination is as poetic as anything in the human experience: In Puerto Viejo, an old barge has been beached for so long that a tree has grown out of its deck. Costa Rica is full of beauty, but that barge will remain with me for as long as I live.

When we surfaced, my ears exploded from the changing pressure, but I could still hear Freddy ask, “You okay? How did you like it?”

All I could do was laugh.

For the first part of the Pura Vía dive series, click here.

Robert Isenberg was a staff writer for The Tico Times. Visit him at robertisenberg.net.