BORUCA, Puntarenas — A shirtless man stands at the top of a gravel road clutching a conch shell in both of his hands. He pushes the spiral shell to his mouth and it emits a deep, trumpeting call. The sound, which marks the beginning of the last day of the traditional Juego de los Diablitos, reverberates through the village. It rattles in through the doors of the homes and sweeps up into the mountains, until with a startled spatter, it suddenly stops. A semi-truck ambles up behind the conch blower and he scrambles out of the way as it passes.

These awkward juxtapositions of past traditions and the modern world are common in Boruca, an indigenous community inhabited by some 2,500 ethnically Brunca people, and in many indigenous reserves throughout the Americas. With the Juego de los Diablitos, or Little Devil’s Game, the Brunca use the turn of every new year to acknowledge and mourn the loss of their culture, while celebrating the traditions they have managed to maintain.

The Juegos have been an annual Boruca tradition for about 400 years, since the Spanish conquest. Observers of the three-day performance watch the Brunca fight off the Spanish.

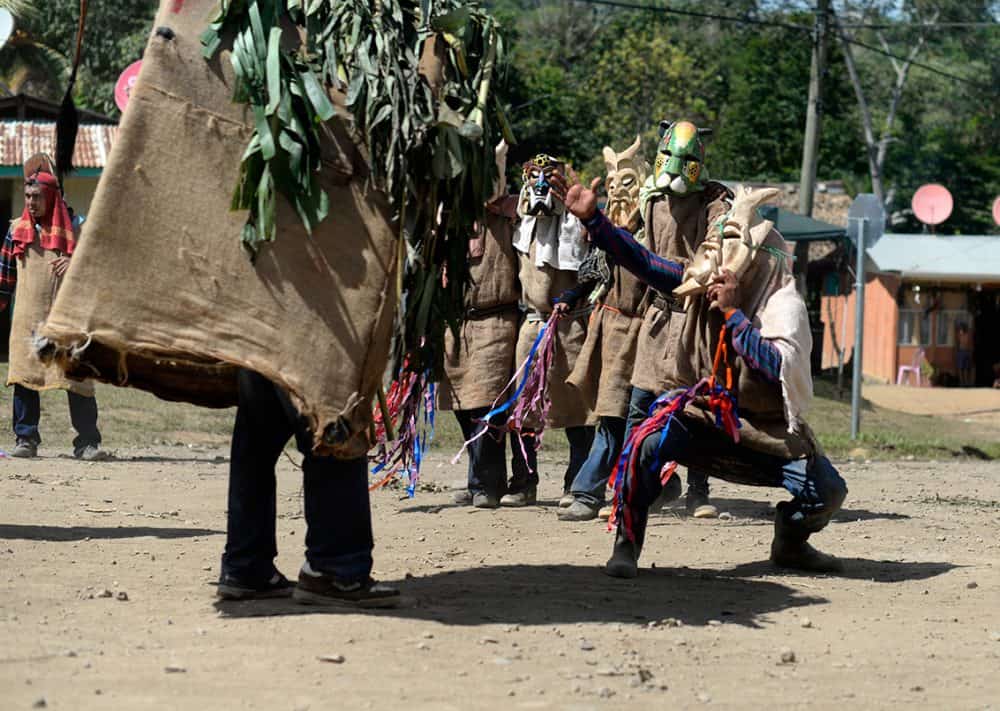

Assuming the role of devils, a jeer used by the Spanish to refer to the unbaptized Brunca, men from the village stage the semi-choreographed battle against a man in a square-frame bull costume, which symbolizes the Spanish.

The games begin at midnight on the night of Dec. 30 with a call from the conch shell, which signals the devils to descend into the village to dance. Dressed in burlap sacks and banana leaf skirts, the devils don the hand-carved masks that have become emblematic of the celebration. Carved from a single piece of balsa wood, the masks depict animals or human forms with devil horns. Each diablito carves and paints his own mask.

The first night of celebrations is followed by three days of combat. Following a small musical band of conch-shell blowers, a flautist and a drummer, the devils move from house to house in the village, dancing and drinking traditional corn beer known as chicha. There the devils begin taunting the bull, which then rams and hits the devils. The fights are not staged and are often violent, with devils thrown into bushes and down hills. By the final day, many of the devils sport deep gashes and bruises, a fact the village elders consider when selecting the devils.

“Women and kids aren’t allowed to participate because it can be dangerous,” said Pedro Rojas, a Brunca guide and lifetime Boruca resident. “They need to be able to handle the heat, the blows and the chicha.”

Chicha consumption is a cornerstone of the Little Devil’s Game, with the performers carrying wooden jugs, horns or, more commonly, plastic two-liter bottles with the brown liquid. Made from corn and sometimes plantains, the chicha does get the drinker drunk, but it also serves another purpose. Packed with calories, the drink helps sustain the warriors through long hours of physical activity with little food.

After days of fighting, the devils and the bull will finally stop in the center of the village on January 2 where the toro finally bests the diablos, killing them all and retreating to the mountains. The story could end here, serving as a yearly replay of the Spanish’s brutal conquest, but it doesn’t. Instead, the head diablo wakes up, and begins bringing the rest of his army back to life. The reawakened devils take to the woods to search for the bull, and then burn the costume when they find it.

The burning of the bull signifies the end of the games each year, but it also symbolizes the endurance of the Brunca people. The Spanish may have won, their language and many other traditions may be struggling against extinction, but the Brunca still live on to fight another day.