The owner of a pescadería invited us to sit down on his bench. “Have a seat!” he exclaimed. “Drink a beer! Relax!” The bench was made of metal, and it was hard on the thighs, but on a hot and humid day in Limón, it’s always nice to take a load off. Beto and I clinked Imperial bottles and drank liberally. A squinty old man with jagged teeth grilled me about my origins.

“The United States!” exclaimed the man, whom I will call Antonio. “I lived in Miami for 30 years!” He started spurting a bunch of facts about American football, about long-retired players and favorite games. He loved living in Miami. He still had family there and in other cities across the U.S. When I asked Antonio when he came back to Costa Rica, he misheard and thought I asked why he came back. He shrugged his shoulders, scowled, and said, “Life happens, you know?”

“Are you from Limón originally?” I asked.

“I was born here!” he proclaimed, punching his chest. He leaned in and growled, “And I’ll die here!” Then he burst into a piratical laugh.

It was noon on the last day of the Carnavales de Limón, one of the biggest annual parties in Costa Rica, and we had just finished lunch at the cevichera next door. Antonio’s little fish market was a flurry of activity – mongers grabbed whole fish from packed ice, random men moved behind the counter, taxistas leaned against their cars in front, and everybody talked quickly and loudly in a mix of Spanish and patois.

A beefy man strode past the glass case full of fish, headed for the street, but then he whirled around and grabbed Antonio’s shoulder.

“Do not trust this man!” he bellowed in English. “He is a – what do you call it? Un ladrón?”

“A thief?” said Beto.

“Yes! This man is a thief!”

The entire pescadería exploded with laughter, including Antonio. It was the deep-throated laughter that only a bunch of old men can pull off, and only after they have been friends for years and years. It reminded me of Pittsburgh – all the craggy steelworkers in the dive bars, lounging in lawn chairs on the sidewalk, waiting for a haircut in an old-timey barbershop.

It was the roughhousing atmosphere of aged testosterone, deep within a port city full of cranes and shipping containers. Years from now, when I remember 2014 in Limón, I will remember these men. I will remember how they begged us to have a second beer and kill some time with them.

“I never loved anyone,” said the beefy man. “But I love rum. Rum is the only thing that never betrayed me.”

Again, a burst of laughter.

That day felt like any other day in a blue-collar town. The men betrayed no anxiety about the Moín Port project, the billion-dollar renovation that has divided the city for the past three presidencies. They said nothing about the Jairo Mora murder trial, which was scheduled to take place within the fortnight. They didn’t even mention Carnaval, which had been raging around them for eight days.

“Did you go to the parade yesterday?” I asked Antonio.

“The what?”

“The parade? For Carnaval?”

He scoffed. His lips actually flapped as he blew irritated air through them. “I don’t care about that. That’s not for me.” And then he said the same refrain I’d heard a hundred times before: “It’s too dangerous.”

I wanted to see Limón during Carnaval, but after a series of miscommunications, I ended up arriving on Sunday – 24 hours after the parade, the drummers, the feathered dancers, the big open-air concerts, and all the most voracious partying. By the time my bus arrived at the Limón terminal at 9:30 a.m., the city was clearly in recovery. Folks in the street had the dazed look of Mardi Gras survivors.

But downtown Limón was also dense with open-air markets, a vast bazaar of interlocked tents and kiosks, where merchants sold high-heeled shoes, floral dresses, fedoras, used TV remotes, plush toys, lingerie of all varieties, “pura vida” T-shirts, and thousands of other items. Women barbequed skewers of chicken on street corners, their faces lost in clouds of smoke.

Most peculiar of all were the merchants – mostly older women – selling random wares out of grocery carts. One grandmother spread out her items on a bed sheet, where a toddler sucked his thumb and watched armies of shoppers march by.

At one end of the long street, the sidewalk was crammed with wood furniture. Rocking chairs shared space with deck chairs and tables and stools and loveseats.

“Where did all this come from?” I asked a merchant.

He was perched atop a stool and looked pleasantly surprised by the question. “Nicaragua!” he said proudly. “Most of it was made in Masaya. We shipped them all down last week, for the beginning of Carnaval. Whatever we don’t sell, we have to take back.”

This was only half the problem, he admitted: Aside from the sea of unsold items, the import taxes had been brutally expensive, which had ruined much of their profits. Everyone I talked with agreed that the first weekend of Carnaval was extremely well trafficked, but this weekend had been a bust. The parade had not attracted the same throttling crowds as last year. “You should have come last weekend,” people told us.

Beto and I had missed the parade, but I didn’t care. Ever since I moved to Costa Rica, I had looked for the excuse to hang in out Puerto Limón. I had arrived on the last day of Carnaval, when Limón’s people were still going through the motions of celebration, but the city was settling back into its usual routine.

This was the in-between period, the day that hotels emptied and hung-over tourists fled the city for parts unknown. They had eaten their fill of coconut rice. They had taken all the pictures and bought all the keepsakes they needed. Most of Limón’s actual stores were closed, their garage doors sealed shut. The street venders looked tired and bored. Nearly everyone on the street seemed eager to head home.

Yet I loved having a full day and night to explore the town. Of all the big destinations in Costa Rica, Puerto Limón is the forbidden city. It is a place to transfer buses, stop for directions, visit a gas station. Given the chance, most travelers skip Limón entirely. But I had to see it. And with so many changes on the horizon, now was the time to go.

I invited my friend Alberto (affectionately known as “Beto”), a staff photographer for The Tico Times and one of my favorite traveling companions. Beto grew up in Costa Rica and is a Carnaval veteran; he had photographed the parade before. He knew the layout of the town and what to expect there. For Beto, visiting Limón was a chance to escape San José and enjoy some Caribbean breezes.

But Beto has a longtime relationship with the city: When he was a kid, his parents would take him on road trips, and one of the requisite stops was Puerto Limón.

“It was a little strange,” Beto recalled to me over lunch. “But my Dad really likes history, so we came here a lot.”

Indeed, the history is palpable. Limón is a weather-beaten place, and nearly every surface could use a fresh coat of paint, including the pedestrian walkway in the middle of town. But if you look past the bundled electrical lines and piles of litter, you’ll see an old town that is shockingly well preserved. You can still discern the antique architecture along its wide streets.

The gridded blocks and ample sidewalks have changed little since the days of the United Fruit Company. The ornate post office in the middle of town is nationally famous, having processed mail from 1911 to 1981. In 2012, the government began an ambitious renovation project to transform the stately old building into the official Limón Museum.

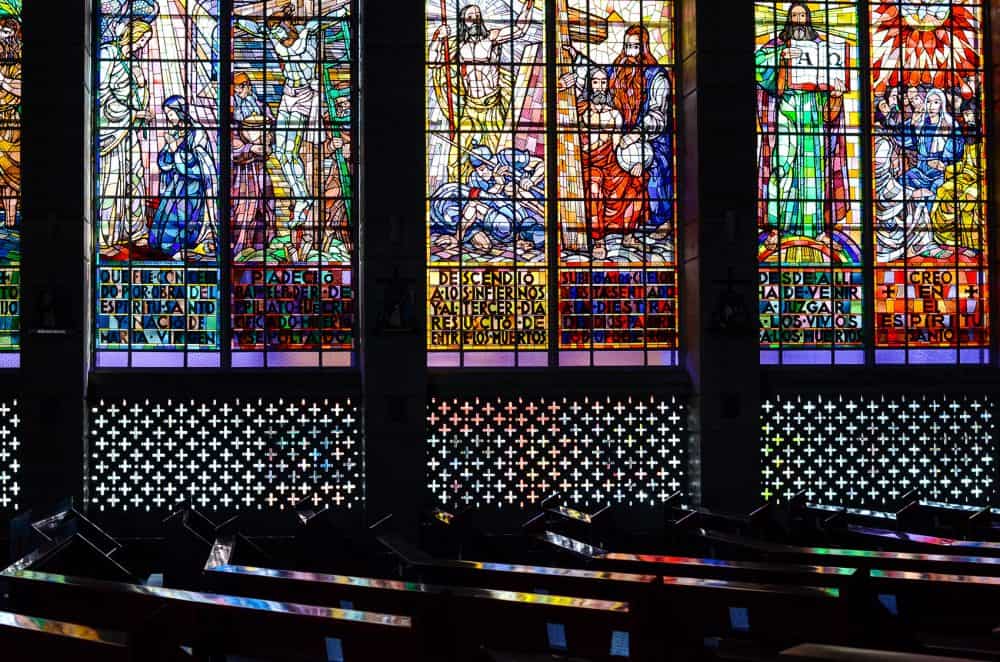

An enormous church stands on the western part of downtown, a concrete structure with a single gray turret jutting sternly into the sky. At first glance, The Sacred Heart of Jesus Cathedral isn’t much to look at; the architecture is downright Soviet. But the church looks more attractive upon closer inspection, and the interior – with its ribbed wood ceiling and sprawling stained glass windows – is surprisingly beautiful. Above the altar hangs a provocative sculpture.

There are three human figures, one embossed passively in the wall, a second that seems to have stepped away from the wall, and a third ascending into the air. The sculpture probably refers to Jesus Christ, but the last figure also outstretches his arms, as if newly liberated from bondage. It seems no coincidence that the figures’ “skin” is dark.

One of the largest and most famous buildings is named after the Black Star Line, the ill-fated Pan-African shipping company created by Jamaican entrepreneur Marcus Garvey in 1919. Garvey had hoped to connect black business owners around the world with a steady flow of maritime commerce; he even dreamed of helping ethnic Africans resettle in Africa.

He was particularly beholden to Limón, where he had worked as a timekeeper for United Fruit in 1910. Like much of Limón’s history, the Black Star Line building is a monument to tragedy: The U.S. government charged Garvey with mail fraud (he advertised a ship he did not yet own), and the company disintegrated. Afro-Caribbean people who had imagined returning to the land of their forefathers never had the chance.

Since its founding, Limón has been the crucible of Costa Rica. In the 1870s, immigrants arrived from Jamaica to build a railroad from Limón’s peninsula to San José. Despite their toil, the workers themselves were segregated from the rest of the country. They were forced to speak Spanish instead of their native English and patois, and the fact that their language survives at all is a testament to their resilience. When the train system was abandoned and dismantled in the 1990s, it was an affront to all that labor.

Ever since I arrived in Costa Rica, friends have related sad stories about Puerto Limón. A bike trail along the coast was never completed. Thoughtful renovation projects never took off. “Narco” drug trafficking plagues the region, a problem mentioned by nearly everyone I met during my stay.

The vocabulary is always the same: Limón has been “abandoned” by San José, “forgotten” by the rest of the country, “failed” by a useless local government and combative trade unions. The place is “dangerous,” and you have to “be careful” and “watch your belongings.” The caution is appreciated but exhausting.

“But I feel like Limón has so much potential,” I told a friend a few weeks before my visit.

“They’ve been saying that for years,” he grumbled.

Still, having lived for many years in the Rust Belt, I have enormous affection for cities like Limón. I don’t mean sympathy. I actually feel more at home in second-tier cities, and I have a passionate, bleeding-heart desire to see them recover. Limón reminds me of Cleveland, that rundown industrial town that could blossom at any second (and already has, as evidenced by its Ohio City district). If Limón had just one successful barrio – even one thriving street – I am convinced the city would radically transform in a matter of years.

The danger, of course, is gentrification. If a few feisty investors dump a bunch of money into trendy businesses, some daring millionaires could buy up all the old buildings and repurpose them as luxury lofts, driving out the current residents. Today it seems far-fetched, but it’s happened hundreds of times around the world. Some of the most fashionable neighborhoods in U.S. cities were once crime-infested slums. Limón is a ripe fruit.

At the gates of the port, we flashed our press badges and the security guards let us in. We made our way into the main marketplace, where local merchants sold knickknacks to tourists. Unlike the Carnaval market, these tables were laden with regular souvenirs: bags of coffee, paintings of toucans, carved wooden bowls, floppy hats with “Costa Rica” written in green, all the usual stuff.

A young woman was offering massages. She was plump and bespectacled, like a bookish Queen Latifah. She said she had grown up in Puerto Viejo, but she now lived and worked in Limón.

“What do you think of Limón?” I asked.

“What do you mean?”

“What’s unique about the city? What makes it special?”

She shrugged, as if I had asked her an impossible riddle. “It’s fine,” she said. “But I wouldn’t live here if I didn’t have a job. I’d rather be back in Puerto Viejo. I miss being there.”

Beto and I made our way outside, crossed the broad parking lot beneath a baking sun, and ambled toward a docked cruise ship.

I once spent three months on a ship, and I know what it’s like to spot land after a few dizzying days at sea. But what do cruise passengers see when they arrive at Limón? I turned around and tried to see the city through their eyes. The portside buildings are low and lined with rust. The sign that reads “Bienvenidos/Welcome” looks old and scoured.

When you drive along the coast and skirt Limón’s airport, the vista is breathtaking; cargo ships rest in a drowsy haze. But looking in the opposite direction, the landscape isn’t as impressive. The rolling hills are too distant to make much of impression. Indeed, it’s hard to tell what you’re even looking at.

Limón handles about 80 percent of Costa Rica’s foreign trade. What does that mean? Picture four out of five items you buy at the supermarket arriving at this port. Those items were packed into a cargo container. The container arrived by ship, it was lifted into the air by an industrial crane, it was fitted onto a truck, and the truck drove that container to your local store.

Port cities are rough by nature. They absorb an endless influx of mariners and their cargo. They must house and feed and entertain those sailors, who spend weeks and months surrounded by water. No one has ever successfully turned Limón into anything but a port city. The community is stripped to its barest essentials – warehouses, stores, restaurants, a couple of hotels, and an unusually prominent cemetery, where the aboveground tombs gleam like ivory. Where other Costa Rican communities have reinvented themselves as tourist meccas, Limón has just gotten more dog-eared. It is what it is.

What do those tourists see, when they head down the gangplank and set foot on Costa Rican asphalt? Until now, not much.

Beto and I took a siesta at the Park Hotel, then ventured back out for dinner. As we descended the hotel’s steps to the first floor, the large plate-glass windows opened onto the sea, which was tinted pink and purple with the vanishing sun. A few people were examining menus in the hotel’s restaurant, but otherwise it felt like we had our run of the place.

What is striking about Limón is its diversity. Like Avenida Central in San José, the streets are a rainbow of different skin tones, heights, builds, ages, and mannerisms. While Limón is most famous for its Afro-Caribbean culture, the city is packed with Chinese-owned shops and restaurants. We ended up with plates of chop suey in a dimly lit eatery.

“¡Con mucho gusto!’ chortled the cherubic waitress as she set down our plates. She smiled sweetly and headed for the kitchen.

Like the old men at the fish market, everyone we had met was friendly. The Caribbean is usually described as “relaxed,” but this was something more – people went out of their way to give us directions and ask us questions. No one minded that we took photos of everything we saw, and some people even posed, giving us thumbs up or crossing arms like tough guys. Men had passed me all day and called out phrases in English – over-pronouncing “How are you, my friend?” as if to prove their command of the language.

As the night thickened, the streets swelled with activity. During the day, the long avenues had been subdued, yet now they pulsed with traffic, shouting vendors, teenagers meandering in packs, couples making out in the doorways, preteens dodging cars in the street. Music pounded from second-story windows; bass vibrated through passing SUVs.

I wanted to preserve this moment, to somehow bottle this bit of history. The city was on the cusp of enormous changes. A week after our stay, local unions protested the Moín Port project, and 68 people were arrested. (To protesting union workers and environmentalists, typically mild-mannered President Luis Guillermo Solís said, “There is nothing to negotiate.”) Soon after that, Limón would host a trial for the suspected murderers of Jairo Mora, the controversial environmental activist.

It was impossible to gauge what would happen to the city, how the Moín Port would be restructured, whether downtown Limón would be renovated, whether daily life would radically transform – or would it change at all? More than any other place in Costa Rica, Limón’s future always seems uncertain, and the city has endured so many disappointments that locals seem resigned to wait and see what happens.

When we retired to our hotel, Beto and I grabbed a nightcap and talked about the city. We had loved our time walking around. For all its problems, Limón is down-to-earth. Friends had warned us of pickpockets and mugging, but we hadn’t once felt unsafe. The only thing the city seemed to lack was something to do, some reason to come back.

I sipped rum – remembering what that man had said earlier, how it was the only thing that had never betrayed him – and looked through the window, at the stone wall that lined the Caribbean sea, where couples cuddled beneath street lamps.

“Pardon me!” came a voice.

We swiveled toward a disheveled man, his face heavily bearded and the skin of his naked arms blemished. He leaned over our table and extended a hand.

“How are you, my friend? You speak English?”

The scene was confusing: The man’s clothes were mismatched, bits of debris was stuck in his hair, and his expression was frantic and wide-eyed. Yet he stood in a fine dining room, surrounded by starched tablecloths and folded napkins.

“Sir, maybe you could help me, please…”

Before he said another word – before Beto or I could say anything – the hotel’s security guard appeared. The guard had a barrel chest and bulbous biceps. His face was stone-serious. He clapped a hand on the bearded man’s shoulder and whirled him around. He growled to the bearded man in threatening Spanish and half-guided, half-shoved him toward the lobby. The man protested meekly, but he knew the jig was up. A second later, the bearded man staggered into the street, and the security guard locked the glass door. They glared at each other through the transparent wall that divided them.

We were sealed inside the hotel now. We could see the dark streets through the walls of windows, but all the entrances were bolted. I felt trapped inside an enormous goldfish bowl. Unlike most buildings in San José, the Park Hotel has no wrought iron bars that encage it, but it was still clear that we were outsiders, and these walls were supposed to protect us from the city. Out there, Carnaval was ending. And the fate of the city? Only time would tell.