GUANGZHOU, China – A sprawling market floor in Guangzhou was once a prime location for shark fin, one of China’s most expensive delicacies. But now it lies deserted, thanks to a ban from official banquet tables and a celebrity-driven ad campaign. One shopkeeper at the Shanhaicheng center quietly ate his lunch at a desk, flanked by four glum-looking colleagues and giant white sacks overflowing with thousands of dollars’ worth of unsold gray stock.

A woman at the next stall over fiddled with her mobile phone, plastic bags of dried yellow fins untouched on the shelves behind her. Outside, the bustling, narrow streets in the southern Chinese city were packed.

“I don’t eat shark fin,” said a 23-year-old shopper surnamed Ling, pausing between a stash of multicolored dried starfish and an assortment of wood ear mushrooms. “It’s dirty. It’s cruel. And I think it’s quite expensive. “Some people eat it because they think it gives them status. But it doesn’t. And I hear it doesn’t even taste that good.”

Fetching as much as 1,600 yuan ($260) a bowl, shark fin soup has long been among China’s most prized dishes, renowned as much for its supposed medicinal qualities as for its associations with wealth and power. “We have a saying that if you eat shark’s fin, it’s good for your health,” one woman working at a dried seafood wholesaler said of the delicacy, which has a bland taste and a chewy consistency.

There is no orthodox scientific evidence for such claims. But the appetites of many Chinese diners appear to have been spoiled by authorities banning the dish from official banquets, and a national anti-shark-fin advertising drive backed by former NBA basketball player Yao Ming and other celebrities.

Austerity drive

Environmental and animal rights groups have campaigned for decades against consumption of shark fin, arguing that demand for the delicacy has decimated the world’s shark population and that the methods used to obtain it are inhumane. Fins are often sliced off while the sharks are still alive, before the fish are thrown back into the ocean to die, despite finning being banned in roughly one-third of countries, according to the Pew Environment Group.

China consumes more shark fin than any other country in the world, according to the campaign group WildAid. The tide began to turn in 2012, when the ruling Communist Party announced a government ban on serving shark fin, bird’s nest soup and other wild animal products at official functions, saying that it would set a precedent that would help protect endangered species.

Around the same time new leader Xi Jinping launched a much-publicized austerity drive for the ruling classes, in tandem with an anti-corruption push that has claimed notable scalps despite a lack of systemic reforms.

WildAid also began its high-profile, celebrity-backed ad campaign on the issue, targeting consumers with the tagline: “When the buying stops, the killing can too.” Demand has since decreased dramatically, the group says, with the biggest impact in Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong province and the heart of China’s shark fin industry.

A WildAid survey released this month said shark fin sales had slumped in the city, with retail prices slumping an average 57 percent and wholesale costs dropping by 47 percent. In neighboring Hong Kong, a major transit point for the trade, import-export volumes have plunged.

The largest category, undried fins with cartilage, went from almost 6,800 tons in 2011 to less than two tons last year, government statistics showed — although dried fins with cartilage still stood at around 3,800 tons.

Several major hotel chains and airlines in the region have banned it and WildAid’s executive director Peter Knight said: “Demand reduction can be very effective. The more people learn about the consequences of eating shark fin soup, the less they want to participate in the trade.”

Government bans on the dish, he added, “helped send the right message and this could be a model to address issues such as ivory”.

Not necessary to kill

At Guangzhou’s upscale Taikoo Hui shopping mall, a 36-year-old businesswoman surnamed Liu said she stopped eating shark fin “two or three years ago.” “It doesn’t taste all that different from eating a vegetable,” she said. “So it’s not necessary to kill an animal in order to eat it.”

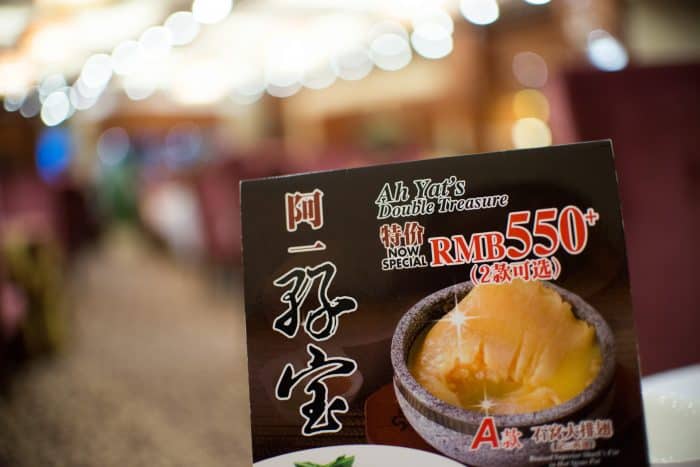

The elegant dining room of the city’s Ah Yat Abalone Restaurant was full of customers, but manager Ye Chaoping said most were there for the abalone — a slow-growing shellfish that is itself the object of concerns about overfishing — rather than the wide assortment of shark fin dishes.

“There’s been a lot of TV ads about it, so more and more people are refusing to eat it,” she said. “These days, a lot of government officials are afraid to eat it, too.”