For a comprehensive account of Costa Rica conservationist Jairo Mora’s murder, see “Why Jairo died”

MOÍN, Limón – It was February, and leatherback sea turtles had just starting arriving to nest on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast when Marielos Morice and I made our drive down the uneven dirt path along Moín Beach.

When the road turned to sand, Morice looked up and yelled for me to stop.

“This is the place,” she said. “This is where they killed him.”

We stepped out of the car and Morice walked me to the spot where police found the body of 26-year-old sea turtle conservationist Jairo Mora in the early morning of May 31, 2013.

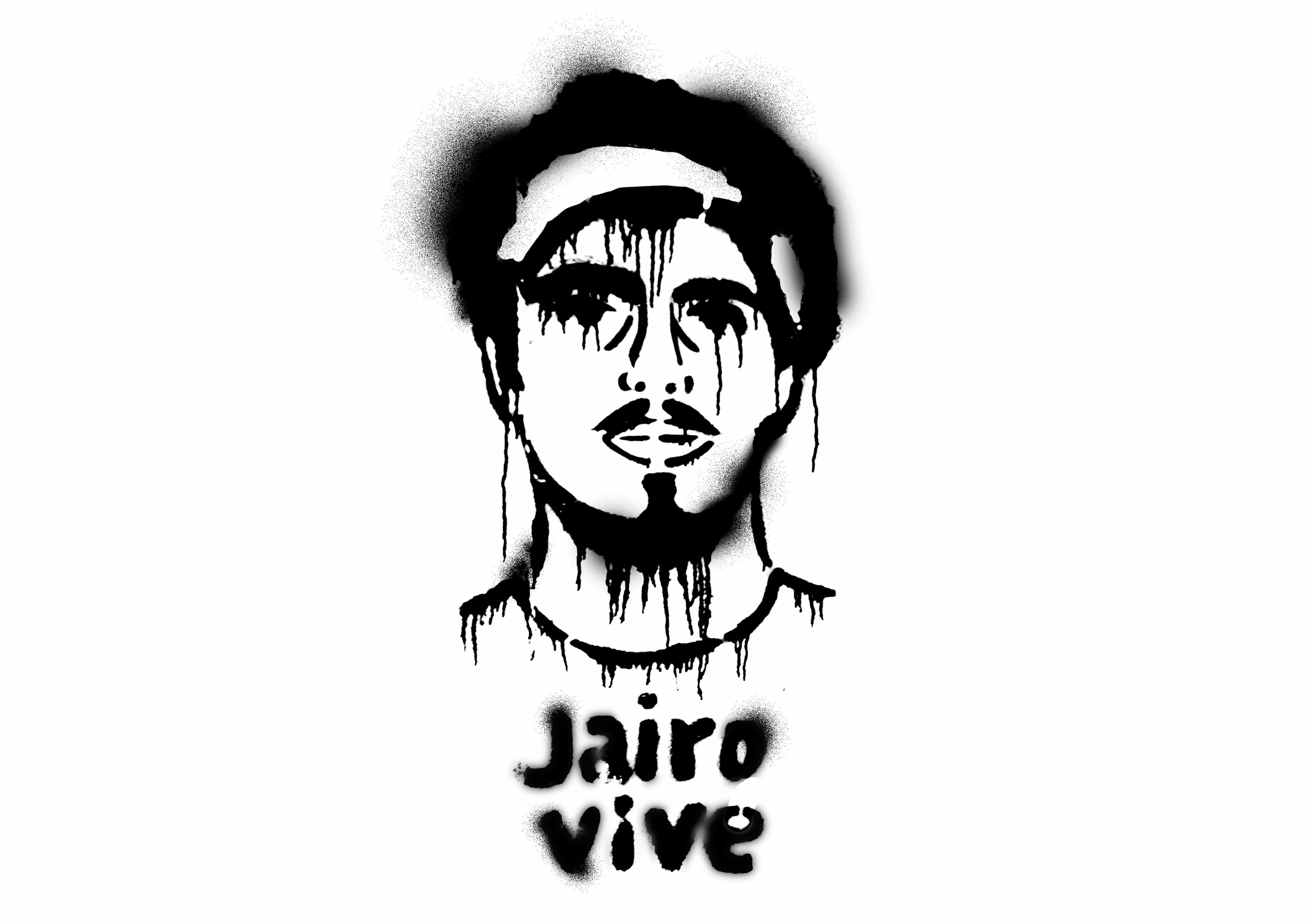

I had expected a memorial or an altar or at least the stencil of Mora’s face that had become ubiquitous graffiti in San José. But nearly a year later, nothing about the patch of beach told the story of Mora’s death or the chain of events that landed seven men on trial for his murder.

The slaying was the culmination of a bitter feud between the beach’s turtle protectors and local egg poachers. It started nine years ago with Morice’s daughter, Vanessa Lizano, when she began leaving her family’s wildlife sanctuary at night to rescue turtle eggs.

Mora, a sea turtle specialist, came to Moín in 2011 to monitor the leatherback’s nesting patterns. He started working with Lizano to protect the beach’s eggs from poachers, and the poachers began to get violent. They delivered death threats to Mora and Lizano and robbed a group of volunteers at gunpoint. When that didn’t work, they captured Mora on the beach one night, beat him, dragged him behind a car and left him to suffocate in the sand.

The bloodshed on Moín drew attention from all over the world, and in Costa Rica the man who had been an unknown activist in life became a symbol in death.

Mora’s dramatic story spread quickly among activists and the media, and it seemed everybody wanted to pick up where Mora left off helping the turtles. But somehow, that never happened. Promises that government agencies and nongovernmental organizations made on television and in Facebook posts didn’t seem to put many boots on the sand in Moín. Now, those closest to Mora have retreated from the spotlight and from the burden of carrying out his difficult legacy.

Tonight when supporters gather for a candlelight vigil in honor of the one-year anniversary of Mora’s death, they will do so on a beach run mostly by poachers, not conservationists. And as for the turtles, they are worse off now than they were on the night Mora died trying to protect them.

On an evening in January, a group of private business owners and well-connected environmentalists gathered in a private room at a Spanish restaurant in San José’s affluent west side. NGO directors, former police investigators and potential vice presidential candidates were all in attendance.

Away from government officials and the mainstream media, the group met in secret, trying to find ways to influence the creation of a national park on Moín Beach.

“The government is constitutionally responsible for protecting these turtles,” said Didiher Chacón, a member of the group and the Costa Rica director for Latin American Sea Turtles (LAST). He was referring to an article in the Costa Rican Constitution that guarantees all citizens a clean and healthy environment. “We can’t have unarmed, untrained conservationists out risking their lives. Their job is conservation, not security.”

Chacón’s hope for a national park is more personal than most in the room. Chacón had known Mora since he was a child, eventually hiring him for the turtle monitoring position that ended in his death.

After Mora was killed, Chacón tried to distance his organization from the incident. He changed its name from Widecast to LAST and permanently closed its programs on Moín.

“Since his murder, Jairo’s name, image, family and mission have been manipulated for other people’s causes,” Chacón said. “We don’t want to involve ourselves in that circus.”

But the circus seems to keep following LAST. Since the killing, turtle volunteer numbers have waned. The organization’s remaining Caribbean program in Pacuare, north of Moín, has 95 percent fewer volunteers this month than at the same time last year.

LAST and other turtle conservation programs are now afraid to put their staff and volunteers at risk on Moín Beach. They are turning to the government for help.

Sipping sangria and munching on tapas, the group laid out their proposal for a 10,000-hectare national park for the beach and the surrounding ocean. The designation would offer Moín’s turtles 24-hour security from park rangers.

An alliance of environmental groups already presented a version of the proposal to the Environment Ministry (MINAE) during a series of open meetings held soon after Mora was killed. The proposal sat on the desk of former Environment Minister René Castro for months, but he had his reasons.

Ministry officials were concerned about the longstanding beach squatter community that has lived in Moín for decades. Not wanting to displace them, Castro’s administration recommended the implementation of a less-strict form of protection, but failed to lay out a final plan for Moín before the ministry changed hands.

With a new government now in power, the group is optimistic they will make progress. They discussed their successful meetings with lawmakers, the potential for presidential support and the funding sure to come from international groups. As the excitement in the room built, one attendee remained quiet.

Vanessa Lizano, the woman who brought Moín’s leatherbacks to the attention of the scientific community and who collected eggs beside Mora for years, had little to contribute.

“It’s hard to stay optimistic that anything will ever change,” Lizano told The Tico Times in an interview before the meeting. “I’m not giving up, but no one else seems to care.”

In the months following the murder, Lizano regularly returned to Moín. She enlisted the help of two young locals, Róger Picado and Margory López. Both barely 5 feet tall, the pair, in their early 20s, looks as if they’ve just entered their teens. The far-from-intimidating trio walked the beach as often as possible. They didn’t save many nests, but they maintained a presence on the beach, and so did the poachers.

Towards the end of the season, Lizano and López were delivering coffee to a friend in Moín in the middle of the day when they were attacked. A masked man pulled out López’s hair and bruised Lizano’s face. He told them if he saw them on the beach again, he would kill them.

Lizano returned to San José, but she hadn’t given up. She lobbied the government and made agreements with foreign conservation groups to send protection. When she returned to Moín in October with a reporter, she still hoped the following season’s eggs could be saved.

Lizano took the group to a bar in Limón that regularly sold turtle eggs. As predicted, the egg-sellers began to cycle through, hawking baggies of the illegal snacks, which sell for $1 a piece and are (falsely) rumored to increase male virility. After a bar fight broke out, police showed up and Lizano got excited. The egg-sellers were still there with their baggies and coolers.

When the police approached one egg vendor, Lizano pulled out her cellphone camera, waiting for the cuffs to come out. But then she saw money change hands, the egg-seller reached into the cooler and handed a bag of eggs to the police.

“If the police don’t care than who is going to?” Lizano said. “It’s time I move on with my life.”

Changing the entrenched poaching culture in Limón was not always on the mind of Vanessa Lizano’s family. Before they began saving turtles, Lizano’s parents just wanted to open a butterfly farm for tourists in Limón’s beachside outskirts.

The design at the Costa Rica Wildlife Sanctuary still reflects this, and pulling off Moín’s dirt road I am greeted by a gate shaped like butterfly wings. In the reception center, a mural of Jairo Mora’s face stared out from the back wall along with the words, “We will never forget.”

In the family home on the other side of the property, three sloths in dog cages nursed electric burns. A furless baby possum kept warm in a Styrofoam cooler and infant howler monkeys screeched from various rooms.

At the center of everything was Marielos Morice, who unpacked groceries with her husband Bernal Lizano while nursing the youngest howler monkey. To support the sanctuary, the family brings in foreign volunteers who pay room and board while helping to care for the sick animals. With Vanessa in San José and no outside security or money, the sanctuary is unable to put any personnel on the beach to protect the turtles.

After Mora’s murder, the Lizanos thought other conservation groups would step in to fill that role. Environmental organizations sent money to Mora’s family and pledged funds to informants in the pending case against Mora’s killers, but no money has gone to Moín.

“After Jairo died, we got all of these offers of help,” Morice said. “Where are all of those people now? We are here all alone.”

The largest reward offer came from the marine wildlife conservation group Sea Shepherd and its leader Captain Paul Watson. The group is known for its aggressive tactics and Animal Planet’s reality TV show “Whale Wars,” which follows the group’s fleet of ships as they face down Japanese whalers in the Southern Ocean whale sanctuary.

Watson pledged $30,000 to information leading to the prosecution of Mora’s killers, and he named Sea Shepherd’s newest ship the S.S. Jairo Mora Sandoval.

Mora’s family and the Lizanos thought the ship would come to Moín at the beginning of turtle season, but a 2002 attempted shipwrecking charge levied against Watson during an anti-shark finning mission has him listed by Interpol as a Costa Rican fugitive. Though Watson is unable to come himself without risking arrest, he plans to send a team once the Costa Rican government gives permission.

“To bring a vessel we need permission from the government,” Watson told The Tico Times. “It has to be a cooperative effort.”

At the very least, the sanctuary expected help from police.

For years, the Limón police followed volunteers from the sanctuary in patrol cars as they collected nests from the beach at night. Then in the middle of 2012, a year before Mora’s murder, the sanctuary received a letter from Erick Calderón, the Limón police chief, stating that his staff would no longer participate in beach patrols. The letter gave no explanation.

The Limón police still makes nightly patrols on Moín beach, but they do not always have a biologist on hand to collect nests as they are found. In the media frenzy following Mora’s murder, Calderón began sending patrol units with Vanessa again, and with the start of the 2014 season, the Lizanos hoped that police would continue.

According to the Public Security Ministry, patrols have increased in April and May, and on Thursday, police arrested two brothers for turtle egg poaching. Police say they have confiscated more than 2,000 eggs from the Caribbean coast since March.

But even with the increased patrols, poachers have found ways to avoid them. Before Mora was murdered, poachers would often trick police by wearing latex gloves and red headlamps that conservationists use to collect eggs. Other poachers would just leave when they saw the patrol car go by and then come back to wait for more turtles to come to shore. Limited resources also mean that turtles are not the primary focus of the Limón police, Calderón noted in an interview. The department’s main responsibility is public safety.

“Moín is a hotspot for criminal activity,” Calderón told The Tico Times in an interview. “We patrol it for drug trafficking and robberies anyway, so if any qualified conservationist calls and asks to accompany us to collect nests, we would be more than willing to help.”

Morice has tested Calderón’s promise, and I was there when she did it. She called the police chief and told him she heard of two turtles killed for their meat since the season started. She pleaded with him to have a car stop by and pick her up. Calderón said a patrol car would be there at 8:30 p.m.

Morice rushed to feed the sloths and put the howler monkeys to bed. Then she headed to the back room and changed into black clothes. She waited until 9, listening for the police car’s horn, then asked me to go wait by the gate.

I walked across the sanctuary’s lawn, wondering whether we’d save any turtles. More than 70 percent of the leatherbacks that nest on Costa Rica’s Caribbean do so during the months of April and May, and the police’s official turtle operations are now winding down. In 2012, the Costa Rica Wildlife Sanctuary saved 1,474 leatherback nests, averaging 80 eggs per nest from Moín Beach. According to a report from the Limón Police Department, patrolmen relocated only 268 in 2014.

From the gate I could see the beach and hear the crash of the surf. If a patrol car went up the beach, it would have had to pass this spot. I started scanning the road for blue and red lights.

“Jairo would sit outside those gates every night and wait for the police to come,” Morice said. “After the letter, they never did.”

They didn’t come this time either.

After nearly an hour and dozens of mosquito bites, I headed back inside. Morice was still dressed in black ready to head out the door. “Are they here?” she asked.

I shook my head. She glanced at the time on her phone and collapsed into a chair.

“Nothing here ever changes,” she said. “Has everyone forgotten about us?”

David Clow and Felix Charnley met while picking up trash.

It had been almost six months since Mora’s murder, and inspired by the young conservationist’s story, both men had joined the newly formed Costa Rica chapter of Sea Shepherd. The Operation Mangrove beach cleanup, where the two met, was one of the new group’s first events.

Charnley, a quiet Brit, had traveled to Costa Rica for a study abroad program, and Clow, a Canadian documentary filmmaker, came for a break after a long project to live and work in what he called “the greenest country on Earth.”

The pair quickly discovered their mutual fascination with Mora’s story and their mutual disgust with the inaction on Moín Beach. Even as they worked under the Sea Shepherd banner, Clow and Charnley didn’t hide their disappointment that the organization was not working on Moín.

Charnley and Clow decided they wanted to act, and they decided the best way to do so would be to create a reality TV show, “The Protectors.”

“This storyline kills anything that is on TV right now,” Clow said in an interview with The Tico Times. “We want to go out there, take back the beach and let this story tell itself.”

The 10-to-13-week series, which will be posted online, will follow a group of six “protectors” as they attempt to take back Moín Beach from poachers. Clow, wheelchair bound from a motorcycle accident for more than a decade, Charnley and the other protectors will patrol the beach on rented horses and four wheelers assisted by an ex-military security force and infrared drones.

“We want to try to make it look cool and fun so more people will want to join us,” Clow said.

“The Protectors” don’t yet have the resources for constant patrols on Moín, but Clow said they hope to save as many eggs as possible before the season ends. They arrived on Moín earlier this week and began joint patrols with help from the Limón police.

Having just arrived on Moín this week, right after the nesting season’s peak, the group is short on time, but even as the last few turtles make their way to Moín’s shores, “The Protectors” remain the only group that has attempted to return to work on Moín. According to Clow, the goal is to protect the turtles on the coast, but for now their actions are “more symbolic than anything.”

The symbolism seems lost on Lizano, who expressed doubts that many eggs can be saved in the last few months of the season. But “The Protectors” have already contacted her for help with the project and she plans to assist if she can.

“If they are going to do this for real, then I am behind them,” she said, “But I haven’t seen anything real in a very long time.”

The weeks leading up to today’s anniversary have been filled with memorial videos, honorary plaques and ceremonies. Conservation groups have organized vigils that will be taking place across the country, including on Moín Beach.

In nearly all of these cases, very few of the people involved in the events ever knew Jairo Mora as anything more than a stencil on a sidewalk or a name in a newspaper headline.

“This whole thing has just become a joke,” Lizano said. “When I go back to Moín it won’t be on the day he died to show off for the cameras. I will go back and visit him for him. He deserves to be remembered for who he was, as a friend.”

Back on Moín Beach, at the spot where Mora was killed, Morice and I began making our way back to my car. As we buckled our seat belts, I mentioned my surprise at the lack of a memorial on the beach.

Morice smiled and pointed to a nearby palm tree with a yellow box and a black number 111 scrawled onto the trunk and another several meters past it with a black 112. They are distance markers, she explained, to keep track of where the turtles had laid their eggs.

“Jairo came out here and painted those down the entire beach, all 19 kilometers,” she said. “Every time I see the numbers I think of him. I thought about spray painting above them with that stencil of Jairo’s face that everyone has, but I think it’s better this way.”