Known affectionately as “Gabo,” the author of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” and “Love in the Time of Cholera” was one of the world’s most popular Latin American novelists and the godfather of a literary movement that witnessed a continent in turmoil following World War II.

The longtime journalist was a colorful character who befriended Cuban leader Fidel Castro, was once punched by fellow Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa and had stated that he wrote to make his friends love him.

Presidents, writers and celebrities mourned his death.

“One thousand years of solitude and sadness for the death of the greatest Colombian of all time,” Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos tweeted.

He later declared three days of national mourning.

Costa Rica President Laura Chinchilla said she was devastated in a tweet while name-dropping some of her favorite works by the author.

“The world has lost one of its greatest visionary writers,” U.S. President Barack Obama said.

The cause of death was not revealed but García Márquez had been hospitalized for pneumonia on March 31 and discharged a week later to recover at his Mexico City home.

His wife Mercedes and two sons were reportedly by his side at home when he died.

The family said his body would be cremated and officials announced a public tribute will be held in Mexico City’s Bellas Artes Palace cultural center Monday.

Born March 6, 1927, in the village of Aracataca on Colombia’s Caribbean coast, García Márquez was the son of a telegraph operator.

He was raised by his grandparents and aunts in a tropical culture influenced by the heritage of Spanish settlers, indigenous populations and black slaves. His grandfather was a retired colonel.

The exotic legends of his homeland inspired him to write profusely. His masterpiece, “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” was translated into 35 languages and sold more than 30 million copies.

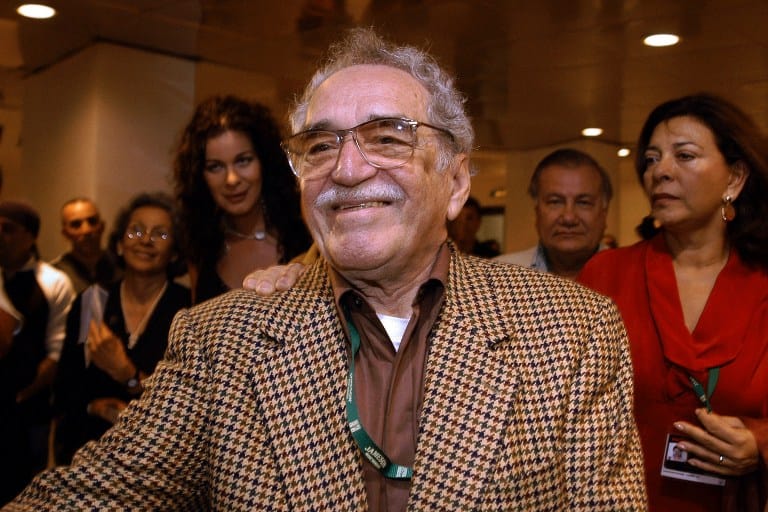

The book, published in 1967, is a historical and literary saga about a family from the imaginary Caribbean village of Macondo between the 19th and 20th century — a novel that turned the man with the mustache and thick eyebrows into an international star.

It was rich in “magical realism,” which García Márquez has described as the notion that behind reality as we perceive it, there is much more going on that we do not understand.

‘Without a penny’

García Márquez wrote the novel after moving to Mexico City in 1961, taking a long bus ride from New York with his wife, Mercedes Barcha, and son Rodrigo.

His second son, Gonzalo, was born a year later in the Mexican capital, where the author lived for more than three decades.

He recalled arriving in Mexico City “without a name or a penny in my pocket.”

The writer faced financial hardship, working for advertising agencies, penning screenplays and editing small magazines.

“As long as there was whiskey, there was no misery,” García Márquez quipped.

The novelist owed nine months of rent payments when he penned “One Hundred Years of Solitude” and could barely afford to send the manuscript to his editor in Argentina.

García Márquez wore a traditional white liqui-liqui costume with a high collar from his region to receive his Nobel prize in Sweden in 1982.

The Nobel committee rewarded him for books “in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent’s life and conflicts.”

In his Nobel speech, García Márquez said it was the “outsized reality” of brutal dictatorships and civil wars in Latin America, “and not just its literary expression,” that got the attention of the Swedish Academy of Letters.

His other famous books include “Chronicle of a Death Foretold,” “The General in His Labyrinth” and his autobiography “Living to Tell the Tale.”

His final novel, “Memories of My Melancholy Whores,” was published in 2004.

Journalist, a friend of Castro

García Márquez also left his mark in journalism, which he considered “the most beautiful profession in the world.”

He founded the Ibero-American New Journalism Foundation in the Colombian port city of Cartagena in 1994.

His first job was with Bogotá’s El Espectador newspaper, which published his first short story in 1947, paying him 800 pesos, or less than $0.50 per month.

He left for Europe after an article angered the military regime at the time, living in Geneva, Rome and Paris, where he finished the 1961 book “No One Writes to the Colonel.”

An admirer of Cuba’s revolution, he became a correspondent for the communist island’s Prensa Latina news agency in Bogotá and New York.

He forged a controversial friendship with Castro, who called him “a man with the goodness of a child and a cosmic talent.”

But he also worked as an emissary between Castro and another powerful friend, then U.S. President Bill Clinton, in the 1990s.

In Mexico, his circle of friends included renowned Mexican writers Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes.

“I write so that my friends will love me,” the novelist quipped.

García Márquez had a falling out with his friend Vargas Llosa that culminated with the Peruvian novelist punching him outside a Mexico City movie theater in 1976.

“We were completely stunned and astonished,” Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska recalled in an interview.

Neither one ever revealed the pair had quarreled.

Vargas Llosa paid tribute to García Márquez on Thursday, saying: “His novels will survive him and continue gaining readers everywhere.”