CHIQUIMULA, Guatemala – The mountainous town of Camotán, 200 kilometers northeast of Guatemala City, is synonymous with hunger: 89 percent of the municipality’s population lives in poverty, water resources are scarce and infant mortality is the highest in the country.

In November 2011, a local nongovernmental organization filed a lawsuit on behalf of five children against the state of Guatemala for failing to protect them against malnutrition.

A judge found the government guilty in what was a landmark ruling in Latin America, but nothing much has changed.

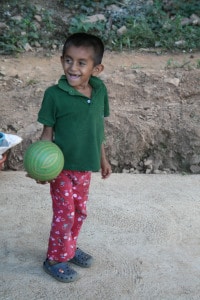

Six-year-old Bryan still lives in a straw hut, with a mud floor, high up in the mountains. He gets tired easily, doesn’t speak much and suffers from a rare growth disorder that doctors say might be a result of a genetic condition or a lifetime of poor nutrition.

“I felt content when they said the judge had resolved the case,” said Bryan’s mother, Santos Floridalma. “I thought, ‘oh great,’ and they said that soon [the government] would have to do things. But now we’re some time on and we haven’t seen anything. The institutions take the word of a judge as a joke.”

According to the World Food Program, Guatemala’s malnutrition rate is the highest in the region and the fourth highest globally. In 2012, the government launched its flagship program to end poverty, called Hambre Cero, but it has yet to reach all areas of the country.

During the court case, Mayra, 4, received a hip operation enabling her to walk properly for the first time in her life, and medication to combat the diarrhea that doctors feared would kill her.

“My daughter was really bad. She had diarrhea and she didn’t get better, just diarrhea every day and every night. I took her to the doctor and he told me it was from birth and that she had little time. We couldn’t continue in this condition,” said Angelina Raymundo, Mayra’s mother.

The judge ruled that the state had violated the children’s human rights to nourishment, an adequate life, health, housing and education, and ordered it to implement 28 actions in order to reduce malnutrition in the area and improve living conditions.

However, the Guatemalan government’s reaction has been slow and poorly executed. The Labor Ministry created textile workshops for about 75 local women, but because there is no market in Camotán for the products they produce, the women who learned to weave are yet to capitalize on their new skill.

“For agricultural workers and small producers, the right to food – recognized worldwide – is linked to the access of land and water. Hunger can no longer be addressed just by assistance policies during period crises. It is urgent to address and bring solutions to the structural issue of land, which is concentrated in very few hands,” said Laura Hurtado, country director of ActionAid Guatemala, which supported the NGO Nuevo Día during the trial.

While the effects of the trial on the families have been small – the most significant change is that each now receives a few extra monthly food rations, such as another bag of rice or a packet of beans – they have been almost nonexistent on the surrounding villages.

“That the judges stated there were violations is of course a result, but the goal right now is that these teachings reach more Guatemalans,” said José Castillo, program coordinator at Nuevo Día, which took the cases to court. “We are facing a government whose public policies don’t respond to Guatemala’s reality. This process, what it wants to do is tell the state to modify its policies. This is the only way to stop poverty and malnutrition.”