FINCA 6, Puntarenas — Everything I had read about Costa Rica’s pre-Columbian stone spheres indicated that it was a total mystery why they were made.

But when I visited the museum between Sierpe and Palmar Sur that houses the world’s largest collection of these orbs, I got the exact opposite impression. I came away surprised by how much we do know, not how much we don’t.

Finca 6 is a fascinating place well worth a visit, with a medium-size museum, an informational video and history exhibits galore. The trails outside lead to scores of the actual spheres, many in their original location.

I have a very simple theory for why pre-Columbian civilization sculpted these rounded beauties: because they could.

As the displays here will tell you, these creations were a triumph of artisanship and organization, and to be able to produce them in large numbers demonstrated a chief’s power over his subjects and one village’s dominance over another. They were status symbols, indicators of power and wealth.

I also suspect (strictly my theory) that it’s no coincidence the spheres are round like the sun and moon, heavenly bodies that were the object of worship throughout the ancient world. I think sculpting these orbs could have been seen as a way of reproducing the heavenly pantheon here on earth.

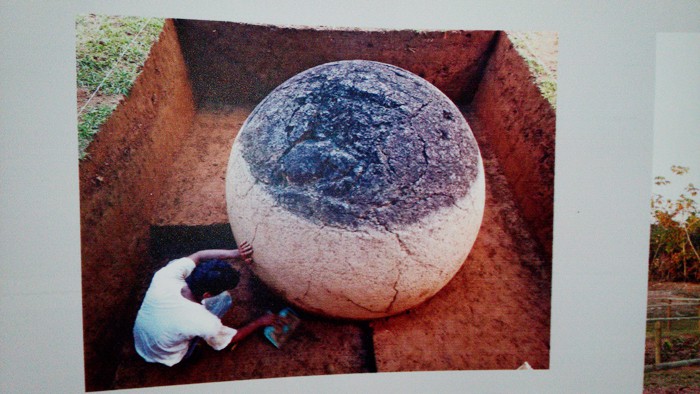

Some 300 of these spheres have been found, ranging in diameter from a few centimeters to over 2 meters and weighing 16 tons. Most are made of the igneous rock gabbro, a type of basalt, though some are made of sedimentary rock, including limestone and sandstone.

There’s a misconception that the sphericity of these esferas (also known as “Las Bolas”) is nearly perfect, although considerable variation exists in their roundness. The daunting challenges of sculpting and transporting these giant orbs has led some to claim they were made by extraterrestrials.

But the most plausible explanations are much more down-to-earth.

How were they made?

Most of the stone used to sculpt the spheres was found in the foothills of the coastal mountains, far away from where they ended up.

“Producing the spheres involved shaping large blocks of igneous rock, such as gabbro, granodiorite and andesite, or sedimentary rocks such as limestone or sandstone,” says an exhibit at Finca 6 labeled “Production.”

“The process involved chipping away at the surface with stone tools; it was possible to loosen layers of rocks with heat, while wooden elements were used to control the sphericity. The surface was treated with abrasives, such as sand, in order to make it even, and the largest spheres were also polished to give them luster or sheen.”

A website called world-mysteries.com says: “This process, which was similar to that used for making polished stone axes, elaborate carved metates, and stone statues, was accomplished without the help of metal tools, laser beams, or alien life forms.”

Museum exhibits say the initial work on the stones was probably done in their original location, then they were transported to their destination and finished in place. How the stones were transported is unknown; the wheel did not exist in the Americas until the Spanish arrived, nor were there beasts of burden.

Even more intriguing, a few of the spheres were somehow shipped as far as Isla del Caño, 17km off the coast. So maybe the aliens helped with that. But I bet even for aliens it would have been a bitch to ship a 16-ton stone in a flying saucer.

Why were they made?

On this question, the archaeologists of Finca 6 speak with far greater certainty.

“The spheres were used as symbols of rank, introduced by powerful individuals on special occasions or to represent their elevated social and political status,” says one exhibit at Finca 6. “The larger and more perfect the sphere, and the greater their number, the greater the prestige and importance of the village and its inhabitants.

“Upon occasion, the spheres were placed to form alignments, following patterns which could have been related to the movement of the sun and other heavenly bodies, indicating significant times of the year related to agricultural cycles and rituals. …

“By means of these objects, the leaders demonstrated their power and consolidated their prestige and position among the others, giving them an important means for controlling transcendental events in the social and religious life of the community.”

Although current law prohibits the moving of any sphere from its original location, a great many have been moved to another place since they were rediscovered in the 1930s. They became popular as lawn ornaments, they adorn the town parks of Palmar Sur and Sierpe, and several are housed in the National Museum in San José. There is one at the National Geographic Society Museum in Washington and another in a museum at Harvard.

So if these stones are so coveted today, wouldn’t they have been even more prized by indigenous cultures that hadn’t even invented the wheel?

Wouldn’t you want one on your lawn, if you could get one?

I see no real mystery in the “purpose” of these spheres. They are spectacular works of artisanship, beautiful in their simplicity. And in ancient times it would have been impossible to possess one, much less a dozen, without having access to the manpower to craft and transport them.

So if you had stone spheres, you were a big shot. And if your village had 30 and the next village had three, it’s a safe guess which community was dominant.

How were they placed?

The inhabitants of the ancient village at Finca 6 built two major mounds with walls made of boulders and trapezoidal access ramps. On top of these mounds, presumably, lived the most important leaders here, the cacique (chieftain) and the shaman(s).

One mound faces the alignment of spheres inside the village, while the other faces outward and has two stone spheres at its entrance.

“The direction of these structures suggests that part of their purpose was to impress visitors, to serve as reminders of their place within the social order, and to project a message of power,” an exhibit says.

If you visit Guayabo National Monument, Costa Rica’s premier archaeological site, you’ll see the village there was also laid out to impress or intimidate visitors, who had to approach the home of the chief by walking up a long, stone road with steps, flanked by guard posts, as if climbing a stairway to heaven.

One informational display at Finca 6 explains that the settlement here was the largest community in the Diquís Delta plain, where conditions were favorable for agriculture, construction and consolidation of power. Peripheral villages closer to the coastal mountain range, the Cordillera Costeña, were of lesser rank and were subordinated to the people on the plain.

“One element utilized to show the hierarchy of the villages and their inhabitants was the possession of stone spheres,” it says. “The spheres could be sent (as a gift or an exchange) from the Delta plain to subordinated or allied communities in order to create a territory under ideological, economic, and military control.”

When were they made?

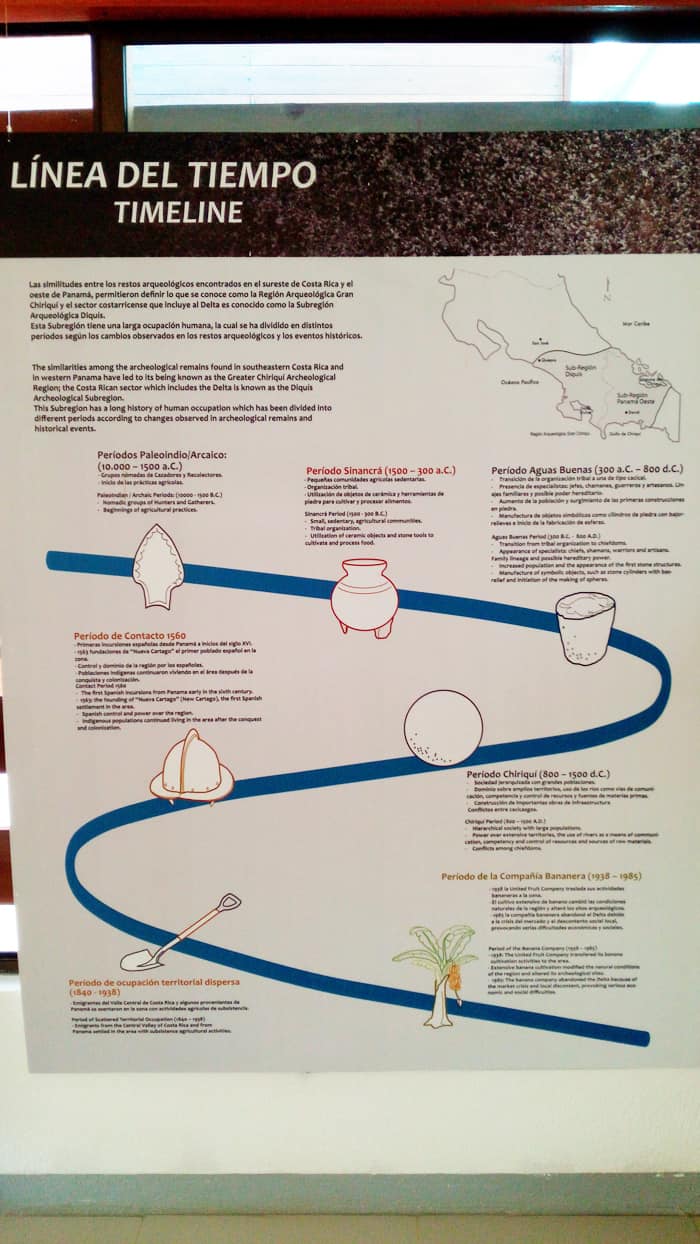

An informative timeline on the history of this region traces settlement here from 10,000 B.C. through the development of agriculture through the rise of chiefdoms led by caciques in the Aguas Buenas Period (300 B.C.-A.D. 800), when specialists like chiefs, shamans, warriors and artists arose, and the first stone spheres were made.

The Chiriquí Period (A.D. 800-1500) saw these populations grow in size and complexity, with hierarchical societies that exercised power over extensive territories, and with conflicts among chiefdoms. This period was the height of the sphere-making.

Early in the 16th century, contact occurred with the Spanish, who built their first capital at Cartago in 1563. With the Spanish conquest, the original inhabitants of the Diquís Delta soon vanished.

But they left us a legacy that led UNESCO to declare “the Pre-Columbian Chiefdom Settlements with Stone Spheres of the Diquís” a World Heritage Site in 2014.

So these spheres are not just a national treasure, they are a world treasure.

And who knows? Maybe even interplanetary.

IF YOU GO

Getting there: You can drive to Palmar Norte from San José via the Inter-American Highway (Hwy. 2) or the Costanera Sur (Hwy. 34). Take the big bridge (Hwy. 2) south over the Río Grande de Térraba, and take an immediate right on the other side, toward Sierpe. You’ll pass through Palmar Sur, and then keep an eye out for a one-lane bridge. Just before that bridge is a blue sign on the left pointing to Finca 6.

Admission: $6 for foreigners, $4 for foreign students, ₡1,000 for Costa Rican nationals.

For more info: http://www.museocostarica.go.cr/en_en/temas-de-inter-s/sitio-arqueol-gico-finca-6.html

Contact Karl Kahler at kkahler@ticotimes.net.