CAHUITA, Limón — There’s an area in the back of Costa Rica’s Sloth Sanctuary that most visitors do not see. More than 100 injured adult sloths are kept in rows of cages here. That might sound bad, but it’s actually much more complicated. Sloths, too, are more complicated than you might think.

Recently, questions arose about this world-renowned sanctuary when a pair of veterinarians who had worked for the rescue center claimed that behind the cute sloths seen by visitors and feel-good stories promoted by the sanctuary owners, a dysfunctional business was operating above the law and mistreating the animals.

An exposé based on their testimony, published by the animal-centric website The Dodo, went viral with more than 4 million shares. Sanctuary founder Judy Avey-Arroyo said the fallout has been a nightmare.

“It’s really vicious,” Avey-Arroyo said. “It’s mind-numbing what’s been happening.”

She and her husband started the sanctuary, located off of Highway 36 along Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast, a quarter of a century ago to care for orphaned and injured sloths. Since then, it’s become famous through its own television show on the Animal Planet channel, a visit from celebrity conservationist Jeff Corwin, numerous published stories and even a t-shirt campaign by American Apparel featuring Buttercup, one of the sanctuary’s sloths.

Avey-Arroyo said no point in the sanctuary’s history has been more trying than this one, where hate mail has swamped her inbox and fewer visitors are showing up for the tours offered six days a week.

The accusations

Avey-Arroyo and her daughter Ursula Avey-Rochté recently took me on a private tour of the Sloth Sanctuary, including the back area of cages. What I saw were enclosures that did little to mimic a sloth’s natural environment. But at the same time, as Avey-Arroyo said, they may be the only practical way to take care of the dozens of animals continually dropped off at the sanctuary.

Despite the animals’ recent fame, researchers really don’t know that much about sloths. What they do know is that sloths learn everything they need to know from their mothers. Avey-Arroyo said it takes a long time for orphaned sloths to learn basic life skills like what to eat, which trees to avoid, and how to hide from predators.

“A lot of them are going to die if they’re freed again without proper rehabilitation,” Avey-Arroyo said. “They have to be taught everything, and a lot of times people don’t understand that.”

Veterinarians Camila Dunner and Gabriel Pastor, who worked at the sanctuary for 10 months before leaving in March, contended in their complaint that Avey-Arroyo exaggerates the difficulty of releasing sloths in order to keep more animals at the center and profit from tourist visits. In their 54-page complaint, submitted earlier this year to the Environment Ministry (MINAE), they also accuse the sanctuary of lacking a management plan, which is required by law, and mistreating sloths by keeping them together in overly cramped cages and feeding them unhealthy diets.

They said zoos have better protocol in caring for animals and providing enough space in cages.

“Many people associate the term Sanctuary with an ‘earthly paradise’ where rescued animals from illegal trade, circuses, etc. are kept,” Dunner and Pastor wrote in their official complaint. “But they do not know that even zoos are more regulated in terms of responsible ownership of animals, including minimum enclosure sizes, healthy diets, enrichment and general management of the various species.”

Dunner told The Tico Times that some of the sloths had been fed dog food. Many of the sanctuary’s tactics, Dunner said, come from a motivation to keep costs low and profits high.

“It turned into just being a business,” Dunner said. “It’s just lack of education to have the sanctuary set up like this. It’s not right.”

Avey-Arroyo and Avey-Rochté said the accusations are a complete lie.

“You invite someone into your life and into your home … and when they make up these lies about you it really hurts,” Avey-Rochté said. “We have no idea why they’re saying this. It just hurts.”

24 years of caring for sloths

Since opening in 1992, the sanctuary’s records show that 770 sloths have been cared for here. Avey-Arroyo said the stated mission has always been to reintroduce the animals back to the wild if possible. She said the sanctuary has documented around 140 successful reintroductions.

“In a perfect world, we would be able to put them all back in the wild,” she said. “In a perfect world, we wouldn’t be here.”

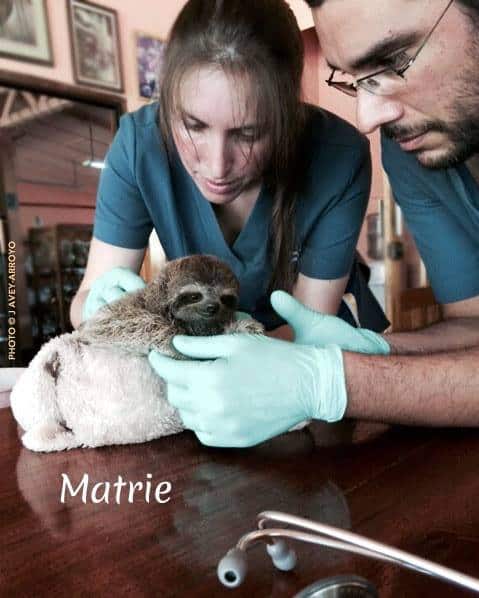

During our tour we also went through the nursery, surgery room, and the exhibition hall where seven sloths are on display for the public. There were no signs of blatant abuse or mistreatment in any of the sections. Most of the sloths that have been brought to the sanctuary have cuts, amputations or developmental issues.

A behind-the-scenes tour proves, at least, that in the section where the adult sloths are caged, sanctuary staff closely monitors their diet and weight progress with twice-daily check-ins documented on checklists.

Avey-Arroyo and her daughter said they were taken by surprise when they heard the laundry list of accusations that Dunner and Pastor made against them in March. Though the vets continually mentioned in their official complaint that they always communicated issues and perceived mistakes to the higher-ups at the Sloth Sanctuary, Avey-Arroyo said at no time did either of the in-house vets express any concerns with how the center was being run.

In emails to Avey-Arroyo during the application process, Dunner admitted that she and her husband had little to no veterinary experience with sloths. So in this war of words, the sanctuary founder said, why is she the one who’s not being heard? How is it that a person who has dedicated 24 years of her life to saving sloths has her reputation questioned by people who have been around the animals for less than a year?

“Because there’s so little known about the sloths, people don’t know how complicated the reintroduction process really is,” Avey-Arroyo said. “If you do put an animal back into the wild, you need to monitor it, which is expensive and requires equipment.

“There’s no sloth sanctuary in the world that knows how to successfully release these animals,” she added.

If sloths could talk

An unavoidable tragedy lost in this debate struck me as Avey-Arroyo showed me the plastic bins in the nursery where baby sloths sleep amid blankets and stuffed animals. There, with these cartoonish, cuddly creatures looking up at me, I couldn’t help but think it funny that these adorable, helpless little things were at the center of so much vitriol and argument. It sounds childish and fantastical, but wouldn’t this whole situation be easier if they could talk? Maybe they could tell us what’s really happening here, if anything, or just tell us what they want.

Sam Trull has been trying to delve into the biological secrets of sloths at her Sloth Institute in Manuel Antonio for two years in an effort to better understand sloths and increase public education about the mammal. Trull, who also works with the Kids Saving the Rainforest organization, runs the Sloth Institute that is in charge of sloth research and reintroductions for the sloths it has on its premises.

Trull believes it’s important to provide recovering sloths with an environment that mirrors their natural habitat as closely as possible. Cramped and stress-inducing spaces like cages, she said, could lead to detrimental side effects when trying to position a sloth for release back into the wild.

“It’s actually a myth that sloths don’t need or use much space in the wild I think because people think they are lazy and therefore sedentary,” Trull wrote in an email to the Tico Times. “In the wild they need a structurally complex environment so that they can move around freely to find food, shelter and other sloths. …Those are all things a tiny cage with few branches can not provide. In addition, lack of movement and ability to exhibit natural postures and behaviors must eventually lead to poor physical and mental health.”

She echoed Avey-Arroyo’s statements about how little is known about sloth biology, and especially reintroduction into the wild. “Nothing in life is risk free, even captivity, but I would much rather take risks that lead to a wild and natural life than to a life behind bars,” she said.

In a scientific sense, it’s unknown how much harm cages cause a sloth, or whether or not it’s better to just leave an injured sloth in the wild. In a legal sense, the Environment Ministry has given the OK for sloths to be kept in cages at the sanctuary, with mandatory checkups.

Shirley Ramírez, who works as a wildlife advisor at MINAE, said ministry representatives are scheduled to visit the sanctuary in the near future to investigate the issues highlighted in Pastor and Dunner’s complaint. On July 5, Avey-Arroyo submitted a response to the complaint that explains or denies each accusation point-by-point.

New law promises to change business of animal sanctuaries

A new regulation mandates that wildlife centers like the Sloth Sanctuary must classify themselves under one of three categories: zoo, breeding center, or rescue center. Under the latter two classifications, the public cannot visit the animals.

When the new law takes effect, possibly later this year, the Sloth Sanctuary will be able to categorize itself as both a zoo and rescue center, Ramírez said, because it is divided into separate areas for both purposes on the same property. So it can continue to take in injured animals and bring tourists who want to see sloths and learn about their habits.

This legal niche is crucial to understanding how the sanctuary operates. The Sloth Sanctuary remains perhaps the most important and recognizable institution for sloth research in the world. And much of that recognition comes from being allowed to bring tourists and do television shows like the 2013 Animal Planet series “Meet the Sloths.”

The show brought worldwide notoriety to the sanctuary, but Avey-Arroyo admits that it was also out of character for a center that purports to focus squarely on healing and helping these animals develop.

“It’s propaganda,” Avey-Arroyo said. “But you know how television is these days. It’s entertainment. We did a lot of things on that show we wouldn’t normally do.”

That was entertainment and this is a business, even if one with an environmental mission. Paying staff salaries, medicine, food, and the list of other expenses is not cheap for any wildlife center. That’s part of why the “Insider Tour” costs $150 and the gift store at the front sells stuffed toy sloths for $40.

At the end of our tour, when we were inside the gift shop, I noticed a large sloth sitting on a wicker hanging chair. I walked by it at first, thinking it was just a statue. But then I saw the sloth move slightly before Avey-Arroyo noticed what I was staring at.

“You didn’t meet Buttercup did you?” she asked.

Buttercup was the first sloth ever taken in by Avey-Arroyo, in 1992. The then-baby sloth had been orphaned after her mother was killed by a car. Now 24 years young, Buttercup remains the sanctuary’s star, even featuring in an American Apparel line of T-shirts.

Avey-Arroyo calls her “an emblematic animal of the Caribbean and Costa Rica.” But she’s not just that. She’s entirely emblematic of this sanctuary and the dilemma it faces.

This sloth that could have died in the wild while only a few months old was instead saved and given a home, which in Buttercup’s case, turned out to be for life. Her image was also made into a T-shirt and she became a TV star.

If you believe Pastor and Dunner, this sloth has become a pet and has been followed by hundreds of other defenseless sloths that generate profits for the sanctuary.

If you believe Avey-Arroyo, it would have been akin to a death sentence to put Buttercup back into the wild at any point. “It’s not even an option we would have ever considered,” she said.

Buttercup sat there swinging in her hanging chair and looking at us while we swooned over her. I thought how strange it is that this harmless ball of fur is at the center of such a polarizing storm. I tried to make sense of it, thinking of how complicated her species is and how little we know about these animals.

Meanwhile, Buttercup kept swinging and staring at us while we openly adored and talked about her. In fact, she was the only one that was silent.