Costa Rican and foreign tourists alike are flocking to the country’s famous beaches during the Holy Week break, but the laid-back mentality that comes with vacation could be a risk for beachgoers.

Between 2000 and 2014, Costa Rica has seen an average of 50 to 60 drownings per year, according to figures from the National University’s International Ocean Institute. That’s a high number relative to the country’s size.

Last year during Holy Week in Costa Rica, seven people died in water-related accidents and more than 50 people were rescued, according to the Costa Rican Red Cross.

Most beaches here do not have lifeguards and many tourists, caught up in their good time, ignore basic safety rules. There has already been one drowning reported this vacation week in Puntarenas, according to the Costa Rican Red Cross.

Luis Hidalgo, president of the Costa Rican Lifeguard Association, said that vacationers tend to let their guard down at the beach.

Plus, visitors to Costa Rica usually aren’t familiar with the water and surf conditions at beaches, and they may be used to swimming at beaches where lifeguards are keeping a close watch for bathers in distress — and have the equipment to carry out sophisticated rescues.

Only a handful of Costa Rica beaches have lifeguard programs, and most of them depend on volunteers. The municipality of Jacó funds a lifeguard program at its beach, while other programs are funded largely by local businesses.

Recommended: Santa Teresa lifeguards get creative to keep beaches safe

Some business owners say visiting beachgoers simply need to take more responsibility for their safety here. Colin Brownlee, owner of Hotel Banana Azul in Puerto Viejo, said coastal businesses shouldn’t be responsible for funding lifeguards because then they would also be held responsible for drownings.

“There’s this thing called personal responsibility,” Brownlee said. “I know it doesn’t exist in the United States but outside of the United States, it does. If I’m in a restaurant and I walk outside and I get hit by a car, it’s not the restaurant’s responsibility.”

Three people have drowned at the beach in front of Brownlee’s hotel in as many years. He said there are signs on the beach warning people of rip currents, and he said his staff advise guests about water safety upon arrival.

“This is public beach. We tell people not to go in and they still go in,” Brownlee said.

He also said about eight members of his staff have received training in water safety, and that he has water rescue equipment stashed in front of his hotel at the beach.

Read also: Drownings in Costa Rica spur experts to call for more lifeguards

This year, higher than normal waves cresting at almost three meters and wind gusts exceeding 19 km/hr are expected at Caribbean beaches, according to forecasts from the University of Costa Rica’s Center for Research in Marine Sciences and Limnology.

Janet Jones of Wahoo Fishing Tours in Puerto Viejo, said the southern Caribbean is “not a dangerous place but you have to use the same sense of caution anywhere.

“People just get vacation brain,” she said. Jones was one of the first responders when a U.S. man disappeared swimming off Playa Negra in January.

On Costa Rica’s Pacific coast, a rash of drownings last year at Flamingo beach near Tamarindo led the community there to organize a private lifeguarding program with help from the Costa Rican Lifeguard Association.

Lifeguard Association president Hidalgo said that the majority of drowning victims in Costa Rica are Costa Rican, followed by U.S. and other foreign visitors. “It’s we Ticos who are dying,” Hidalgo said.

He thinks some Costa Ricans don’t take water safety seriously because they believe it’s something that only affects foreign tourists.

“Accidents are going to happen,” he said, but that doesn’t mean they’re not preventable. “We don’t want a Holy Week in mourning.”

Tips for staying safe at Costa Rica beaches

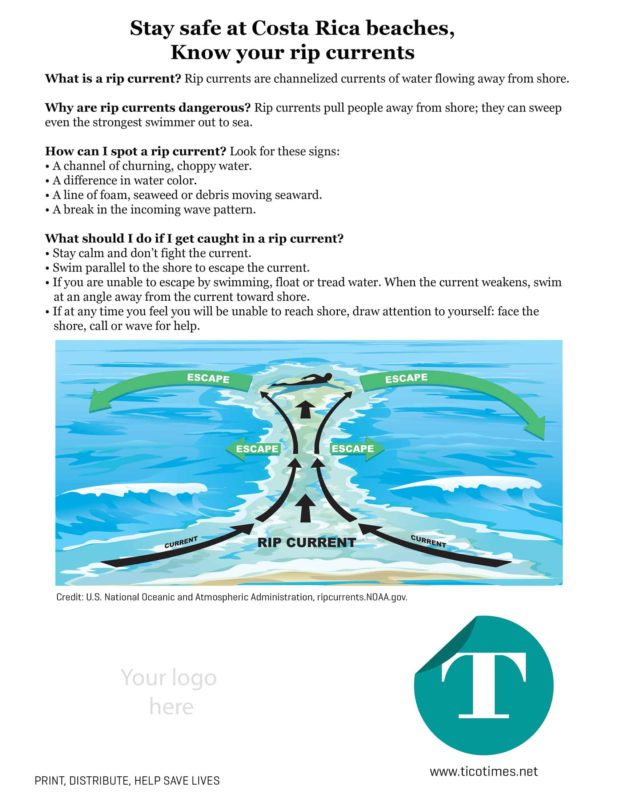

Alcohol consumption and rip currents are some of the main causes of accidents at Costa Rican beaches, Hidalgo said. A rip current is a channel of water flowing away from the beach toward the open ocean, sometimes very quickly.

If swimmers find themselves caught in a rip current, also known (though incorrectly) as a riptide or undertow, they should not fight it. Often swimmers who get caught in rip currents exhaust themselves trying to swim toward shore against the water’s flow, and that leads to drowning.

Instead, swimmers should swim parallel to the shore to get out of the current’s grasp and then, once they escape the current, swim back into shore.

Hidalgo shared some other tips for bathers at the beach:

- Be mindful of alcohol consumption before swimming.

- Locate nearby emergency services.

- Ask locals where rip currents or other hazards are if you’re not familiar with the beach.

- Know your limits as a swimmer. When in doubt, stay out of the water.

- Stay alert and keep a close eye on children.

For more information, check out the following fact sheet on rip currents. Please feel free to print and distribute:

Michael Krumholtz contributed reporting.