In 1974, a California surfer and businessman named Danny Fowlie tracked down one of the world’s greatest left surf breaks, bought all the land in front of it, founded the town of Pavones, became “King of Pavones,” and then lost this multimillion-dollar windfall to squatters when he went to prison for 18 years on U.S. drug-trafficking charges.

And then the plot thickens.

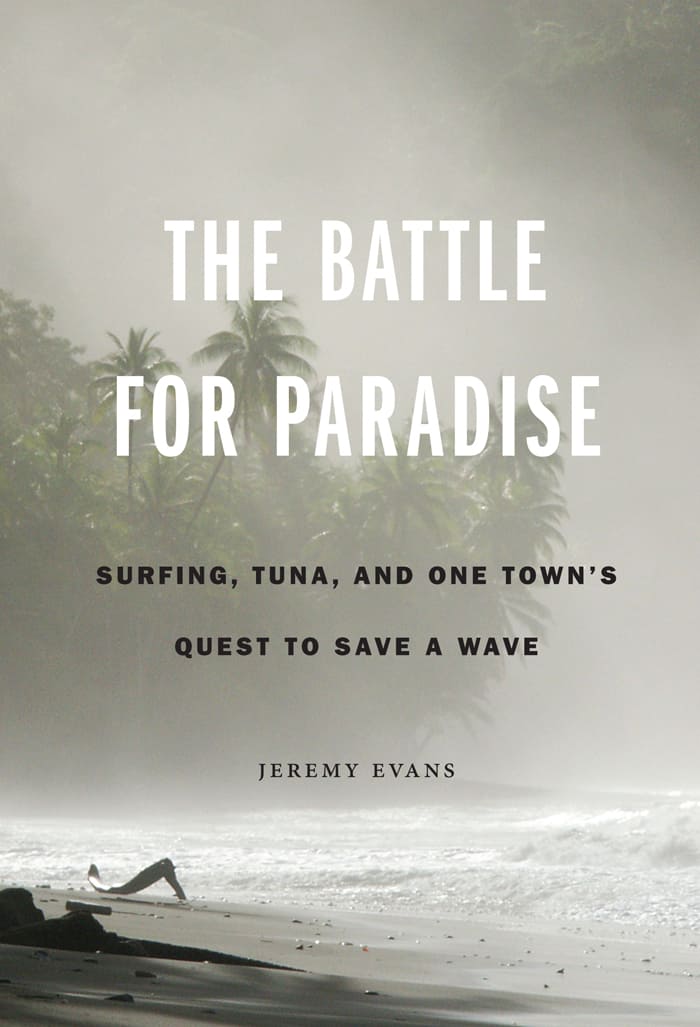

In a fascinating new book, “The Battle for Paradise: Surfing, Tuna, and One Town’s Quest to Save a Wave,” Jeremy Evans relates how the “squatter wars” in the southwest Costa Rican surfing mecca of Pavones created constant confrontation, with one Gringo and at least two Ticos killed in the violence that followed, but with few police to investigate and the government in Golfito mostly siding with the squatters.

As if they had time, the people of Pavones next found themselves swept up in a brand-new battle royale — less violent but more uphill — against a tuna farm already approved by the government to be installed just south of their famous wave, threatening to choke their cash cow (surfers) in tuna shit.

Evans masterfully lines up three stories in one — Fowlie, squatters and the tuna farm — and pulls off the sequence like a lucky gambler hitting three cherries in a row on a slot machine.

The result is a triumph of boot-leather reporting and narrative nonfiction, with a rare twist: There is nobody in the story who “declined to be interviewed,” and in fact the author appears to have talked to every major player in the story, often for hours, and can quote them for paragraphs on end.

Evans, who currently teaches English in a high school and a community college in South Lake Tahoe, California, is also the author of “In Search of Powder: A Story of America’s Disappearing Ski Bum” (2010).

His primary narrative in the new book follows the fight between a small Costa Rican surfing economy and a foreign tuna farm. Peruvian aquaculturist Eduardo Velarde had a 21st-century idea, and he had good Spanish money behind him: Start a tuna farm and figure out how to hatch tuna from eggs – a possible solution to the overfishing of the most eaten fish on the planet.

Problem was, the people of Pavones didn’t want a foreign tuna farm in their waters, and they organized vociferously against it. What was the harm? Well, for starters there was all the tuna feces that it might deposit along the famous wave that was the economic engine of Pavones.

Velarde lambastes all arguments against his tuna farm in extensive interviews in the book, but ultimately his project was rejected by the local population and his funding was pulled. The final straw appears to have been the organized opposition of the international surfing community.

The tuna farm saga is a good story, but in Pavones good stories tend to stack up on top of each other, and in all of them Fowlie is either front and center or lurking closely in the background.

He plays a central role either by his presence (handing over fistfuls of cash to backwater Ticos in the 1970s to build a town) or by his absence (when the squatter invasion of 1985 brought fear and even death to this place).

Evans walks a difficult tightrope with Fowlie, exploring the seemingly split personality of the larger-than-life figure, who comes across as both do-gooder – founder and patron saint of Pavones – and ne’er-do-well – head of what Evans called the biggest marijuana-smuggling operation in the western United States.

The one thing the book doesn’t need is a prolonged defense of the right of non-surfers to write about surfers. The proof is in the pudding, Evans, and you’re in.

Finding Pavones

As the book relates, Fowlie first flew to Costa Rica in 1974, in a chartered plane with his family, looking out his window for a big left surf break that a friend had told him about years before.

As they flew over a desolate coastline near the Panama border, he finally spotted it – a beautiful, blue, breaking wave that seemed to go on forever, with nobody surfing it and nothing in front of it but a house and a crude sawmill. The wave was a machine, a surfer’s dream, and nobody knew about it.

That same day, Fowlie tracked down the owner of the property, Claudio “Cullo” Lobo, in a bar in Golfito, and said he wanted to buy it. Lobo took him by canoe to see his 250-acre finca.

“I could see waist-high waves,” Fowlie says in the book. “They were perfect, and they were wrapping around this point and right out in front of Cullo’s property with its sawmill.”

Fowlie said he would take it. Lobo said it would be $50,000.

“That is way too high. Make it thirty thousand. I’ll give you ten thousand now and the other twenty thousand later when the paperwork is in order,” Fowlie said.

“Okay,” said Lobo.

Chaos in paradise

Eleven years later, the book relates, the manager of Fowlie’s desert ranch in remote Southern California, Wayne Westmoreland, got drunk at home in South Laguna and shot a gun inside his own house. When police responded, they found 20 pounds of marijuana, $73,000 in cash and “numerous ledgers and bank records.”

Wayne rolled and said he was working for Fowlie, who had a property called Rancho del Río, on the Riverside-Orange county border, that was used to store marijuana by the ton.

A SWAT team raided the ranch, arresting two people and, according to Evans, finding $23,000 in cash, 50 rifles and shotguns, three automatic weapons, a cash-counting machine, multiple shipping boxes and remarkable quantities of aromatic fabric softener sheets, apparently intended to mask the pungent smell of fresh cannabis.

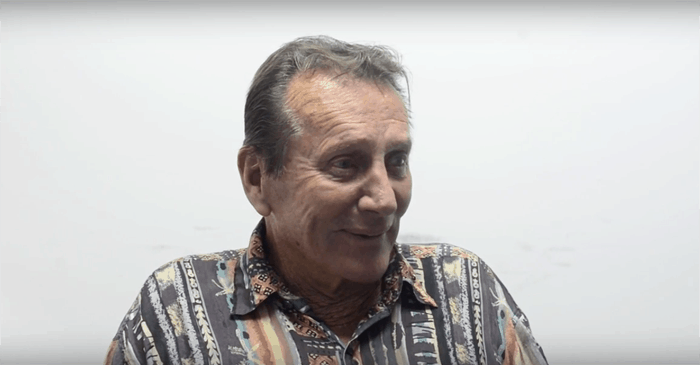

(Fowlie, in an interview with The Tico Times, denied that there were so many weapons, and he was baffled by the report of fabric softener sheets.)

To make a long story short, Fowlie was convicted of 15 federal charges and served 18 years in prison in Mexico and the U.S. He still claims to be the rightful owner of everything he ever bought in Pavones – which is virtually all of it.

Outside the scope of this book is another controversial project that has divided this town – the construction of the 60-unit beachfront Pavones Point condominiums (on land that Fowlie still claims as his), as explored in a Tico Times article last July.

It’s hard to believe, but things happen so fast in Pavones it may be time already for a sequel.

Watch: “The King of Pavones” from Love Machine Films.

Read the text and watch the videos of Dan Fowlie’s wide-ranging interview with The Tico Times.

“The Battle for Paradise: Surfing, Tuna, and One Town’s Quest to Save a Wave” is available on Amazon.