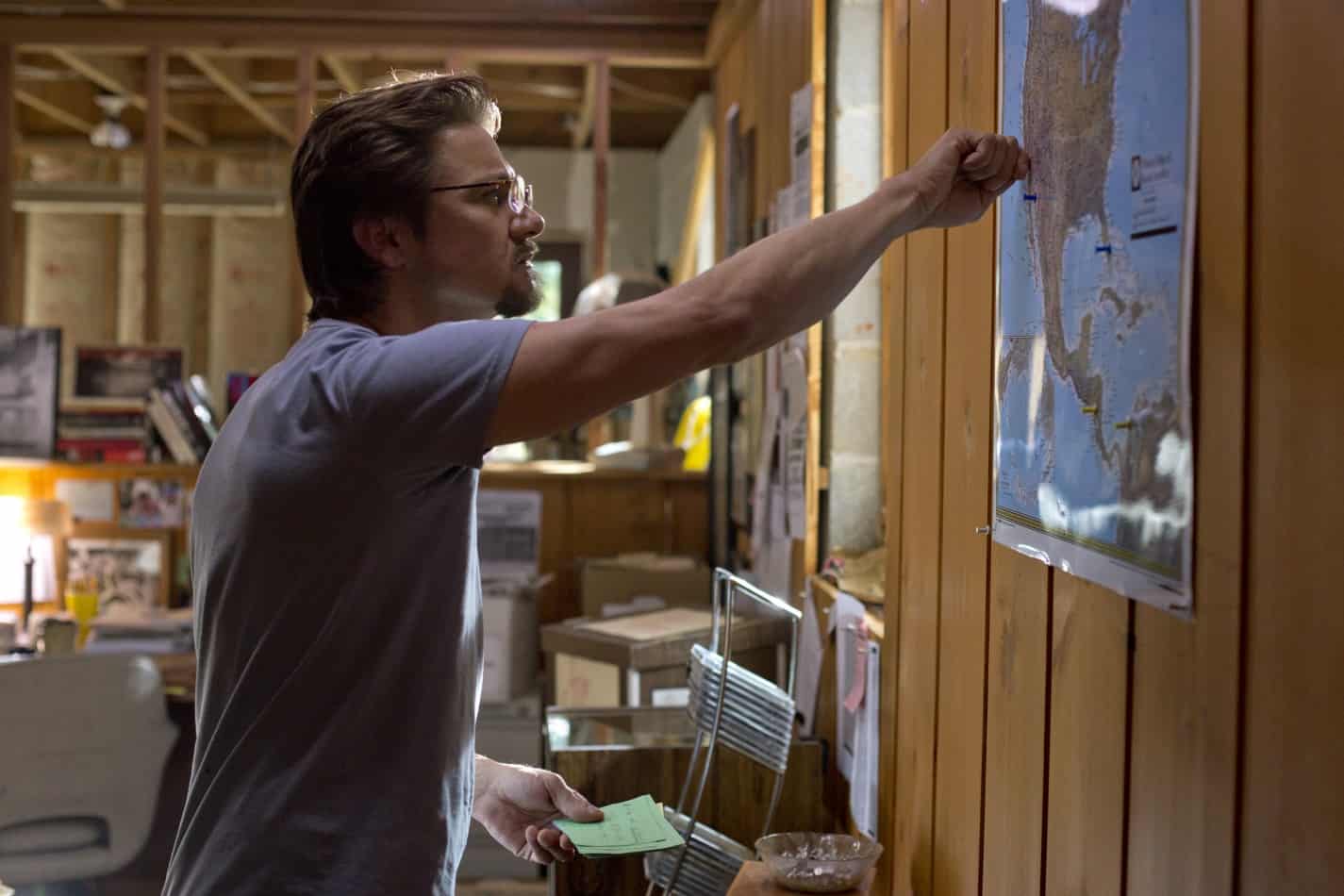

The feature film “Kill the Messenger,” directed by Michael Cuesta and starring Jeremy Renner, opened in theaters across the United States in mid-October. The film tells the story of an enterprising reporter who stumbles on the biggest story of his career: the crack epidemic in Los Angeles having roots in the CIA’s funding of the Nicaraguan Contras a decade earlier. Webb goes after the story and ultimately pays with his career and his life. (He died at the age of 49, alone and unemployed, on Dec. 10, 2004. His death was ruled a suicide).

Gary Webb was not the first to write this story. In December 1985, Associated Press reporters Robert Parry and Brian Barger first broke the story of a Contra-drug connection in their piece “Reports Link Nicaraguan Rebels to Cocaine Trafficking.” But their story was largely ignored by the rest of the media – after all, it would be another 10 months before Wisconsin native Eugene Hasenfus was shot down over Nicaragua, and a business card in his wallet led straight to the White House. The unraveling of a complex enterprise eventually called “The Iran-Contra Scandal” remains a dark chapter in U.S. political history.

Recommended: The exposure of Eugene Hasenfus

But Gary Webb’s three-part series, totaling about 20,000 words and published in August 1996 in the San Jose Mercury News – a small, regional paper in California – broke into the public’s consciousness for two reasons. First, as Robert Parry wrote in a 2011 article: “Webb’s series wasn’t just a story about drug traffickers in Central America and their protectors in Washington. It was about the on-the-ground consequences, inside the United States, of that drug trafficking, how the lives of Americans were blighted and destroyed as the collateral damage of a U.S. foreign policy initiative.”

The second reason was the Internet. The San Jose Mercury News was one of the first newspapers in the country to understand that its website was not simply a place to post PDFs of their print edition.

The series was released over three days, and each installment featured links to source material and even audio clips – which was unheard of at the time. The website for the series was well designed and compelling, even by today’s graphic standards. The paper itself wrote at the time: “‘DARK ALLIANCE’ represents the San Jose Mercury News’ most ambitious attempt to date in using the World Wide Web to deliver a news story.”

The use of the Internet allowed the small paper to have a global reach, and it did. At the height of viewing, the site had over 1.3 million hits per day. (The New York Times, by comparison, in Fall 1996 was averaging less than 1 million hits per day and only topped 1.5 million in November following the crash of TWA Flight 800.)

But in one sense, without being too trite, Webb’s reporting suffered because he did not have “the Web” to research his topic. Jeff Cohen, co-founder of Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, notes that there was plenty of evidence to support Webb’s story in Senator Kerry’s drug hearings in 1986, or Lt. Col. Oliver North’s handwritten notebooks that came before the Iran-Contra investigators in 1987. The problem is that Webb would not have easily found copies of those to read in the San Jose Public Library in 1996. (By contrast, in researching a story on Eugene Hasenfus earlier this month, with four clicks of the mouse, I could read part of the transcript of a 1990 trial in federal court in which a former CIA agent discussed using Radio Shack “fuzz busters” for a radar detector in a Contra resupply plane.)

Gary Webb was, by his own admission, in new territory. He had never done an investigative story of this kind. His specialty was investigating government and private sector corruption – first in Ohio, then in San Jose, a city of less than 850,000 at the time. He had never done an international story; he had never done a Washington, D.C. story, either. He had no contacts, but he had gumption. Gary Webb was the old-style 20th century news reporter: If he was doing a story on a court proceeding, he went to the court; if he was doing a story about drugs in Los Angeles, he got out of the car and walked in the neighborhood. Webb took to heart the slogan of John Ross, the great journalist of Mexico and San Francisco, who would say, “Ir a lugar de los hechos”: Go to the scene of the crime. And Gary Webb did go. His investigation took him into prisons in L.A. and Nicaragua, to secret airstrips in the jungle, and to dangerous neighborhoods in his own state.

Dark Alliance rattled a lot of cages – it led to a Congressional investigation, and ultimately a CIA Inspector General’s report, which would corroborate some of Webb’s findings. But the San Jose Mercury News’ scoop also shook up a lot of the newspaper world. The New York Times, L.A. Times, and The Washington Post all went after Gary Webb to tear down his credibility and that of the story. Some of these attacks were no doubt spurred by personal jealousy, but recently declassified CIA documents, described in a report last month by Ryan Devereaux writing for The Intercept, tell a darker story. A six-page report titled “Managing a Nightmare: CIA Public Affairs and the Drug Conspiracy Story” explains how the CIA used its “ground base of already productive relations with journalists” to quiet the impact of Webb’s reporting.

Gary Webb resigned from the San Jose Mercury News in November 1997, but he continued to follow the trail, and he eventually released an expanded version of the reports as a book in 1998, with all of his sources listed. However, he would never work as a journalist for a daily newspaper again.

Now, with a major film in theaters, people are again remembering the work of Gary Webb, and 10 years after his tragic death, realizing that a lot of what he had to say was absolutely right. But it is also occasioning a new attack on Webb’s work. The most recent piece, “Gary Webb was no journalism hero, despite what ‘Kill the Messenger’ says,” is by Jeff Leen, assistant managing editor for investigations at The Washington Post. Leen, who joined the Post the year after the Mercury News stories broke, like so many others who attacked Webb’s reporting 14 years ago, wrote last week: “Webb’s story made the extraordinary claim that the Central Intelligence Agency was responsible for the crack cocaine epidemic in America.”

In fact, Webb’s reports never said that, they said: “The [Contra] army’s financiers – who met with CIA agents both before and during the time they were selling the drugs in L.A. – delivered cut-rate cocaine to the gangs through a young South-Central crack dealer named Ricky Donnell Ross.” He was talking about foreknowledge and perhaps “blind-eye” oversight by the members of the CIA – a fact somewhat acknowledged in the CIA Inspector General’s own report of December 1997.

The official report, while seeking to downplay the claims in Dark Alliance, does admit some parts were true:

We found that the allegations contained in the original Mercury News articles were exaggerations of the actual facts. … It is clear that certain of the individuals discussed in the articles, particularly Blandon and Meneses, were significant drug traffickers who also supported, to some extent, the Contras. … While the Department of Justice’s investigative efforts suffered from lack of coordination and insufficient resources, these efforts were not affected by anyone’s suspected ties to the Contras.

Former U.S. Senator John Kerry, who now is Secretary of State, was less forgiving in his comments to The Washington Post on Oct. 4, 1996: “There is no question in my mind that people affiliated with, on the payroll of and carrying the credentials of the CIA were involved in drug trafficking while involved in support of the Contras.”

Joel Bleifuss, writing on Oct. 28, 1996 for In These Times, had a different perspective than Webb’s detractors: “One profoundly troubling aspect of this burgeoning scandal is how the mainstream news media have chosen to cover – or not cover – this story.”

Leen writes, “The New York Times, The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, in a rare show of unanimity, all wrote major pieces knocking the story down for its overblown claims and undernourished reporting.” Too bad they did not devote that energy to following up on the leads opened in 1985 by Bob Parry, illuminated in the 1986 Kerry hearings (the United States Senate Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics, and International Operations), and refueled by Gary Webb’s 1996 on-the-ground reporting.

—

Norman Stockwell is a freelance journalist based in Madison, Wisconsin, and serves as operations coordinator for WORT-FM Community Radio. He first met Gary Webb in the summer of 1998. See his stories in recent Tico Times special editions marking the arrest of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet and the 30th anniversary of the La Penca bombing.